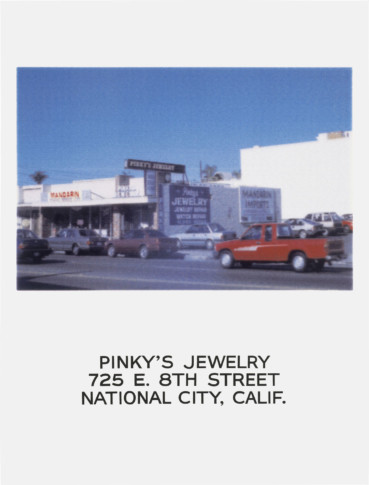

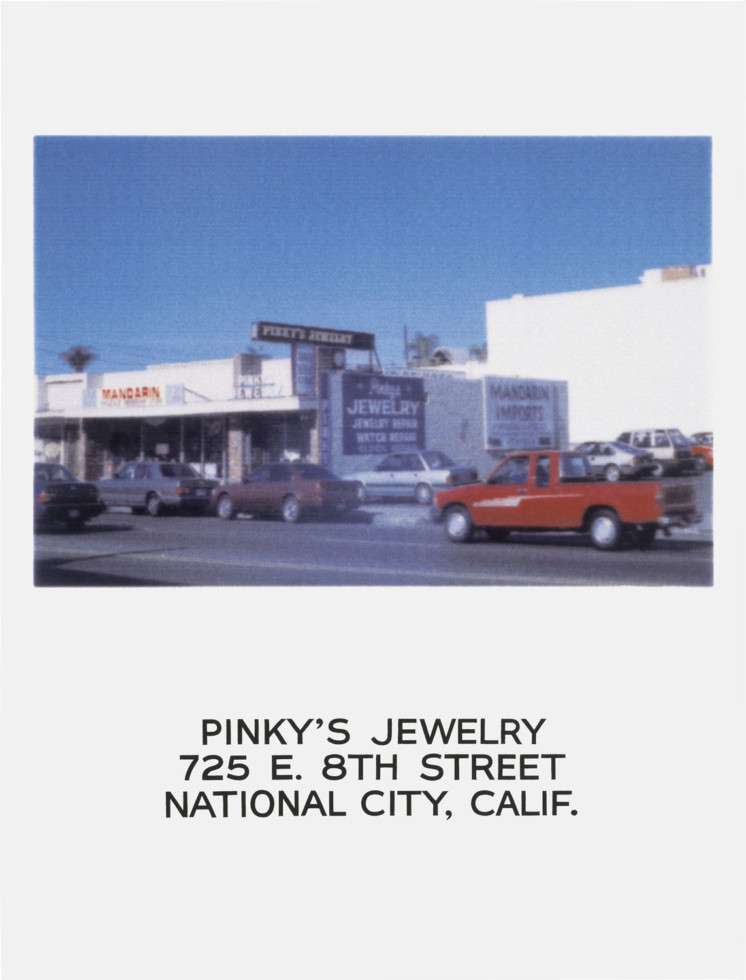

John Baldessari, Pinky's Jewelry, 725. E. 8th Street, National City, Calif., 1996 © The Estate of John Baldessari. Courtesy the Estate of John Baldessari and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

Introduction John Baldessari

Text: Matilda Olof-Ors

An artist is a person who can see connections in unlikely circumstances. [1] John Baldessari

In the mid-1960s, the American artist John Baldessari (1931 – 2020) came to the realization that a photographic image or written text was better able to express his artistic intentions than a representational painting. This insight made him re-evaluate not only painting as such, but also what defines art, how art is made and what art can look like. In his work, he increasingly disregarded the notion that art and photography are two separate fields. By bringing together linguistic investigations and unexpected motifs, Baldessari created Conceptual artworks for over 50 years that with an underlying sense of humour and a streak of irony have time and again challenged the prevailing norms and limits of art.

Since his first exhibition in 1960, Baldessari had over 200 solo shows and participated in more than 1 000 group exhibitions. And despite maintaining that “you can’t teach art”, he also supported himself through teaching jobs for many years. After a few years of teaching at various schools in the San Diego area, Baldessari was invited to CalArts (California Institute of the Arts), the newly opened art academy north of Los Angeles, in 1970. The teaching at the school was characterized by an experimental atmosphere, with no curriculum and a non-hierarchical relationship between the teachers and students. Alongside colleagues such as Nam June Paik, Allan Kaprow and Alison Knowles, Baldessari came to influence several generations of artists educated at CalArts. Despite his prominence on the international art scene and his asserted influence as a teacher, he has remained relatively unknown in Sweden. This exhibition at Moderna Museet marks the first comprehensive presentation of his work, encompassing key aspects of John Baldessari’s long and extensive career.

Language and text became essential tools for Baldessari as for many other artists who at the time strove to focus on the idea behind the artwork, rather than its aesthetic qualities.

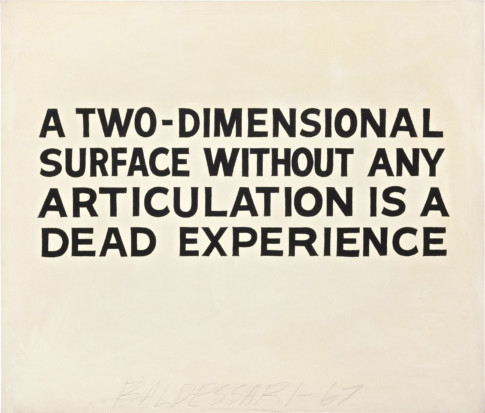

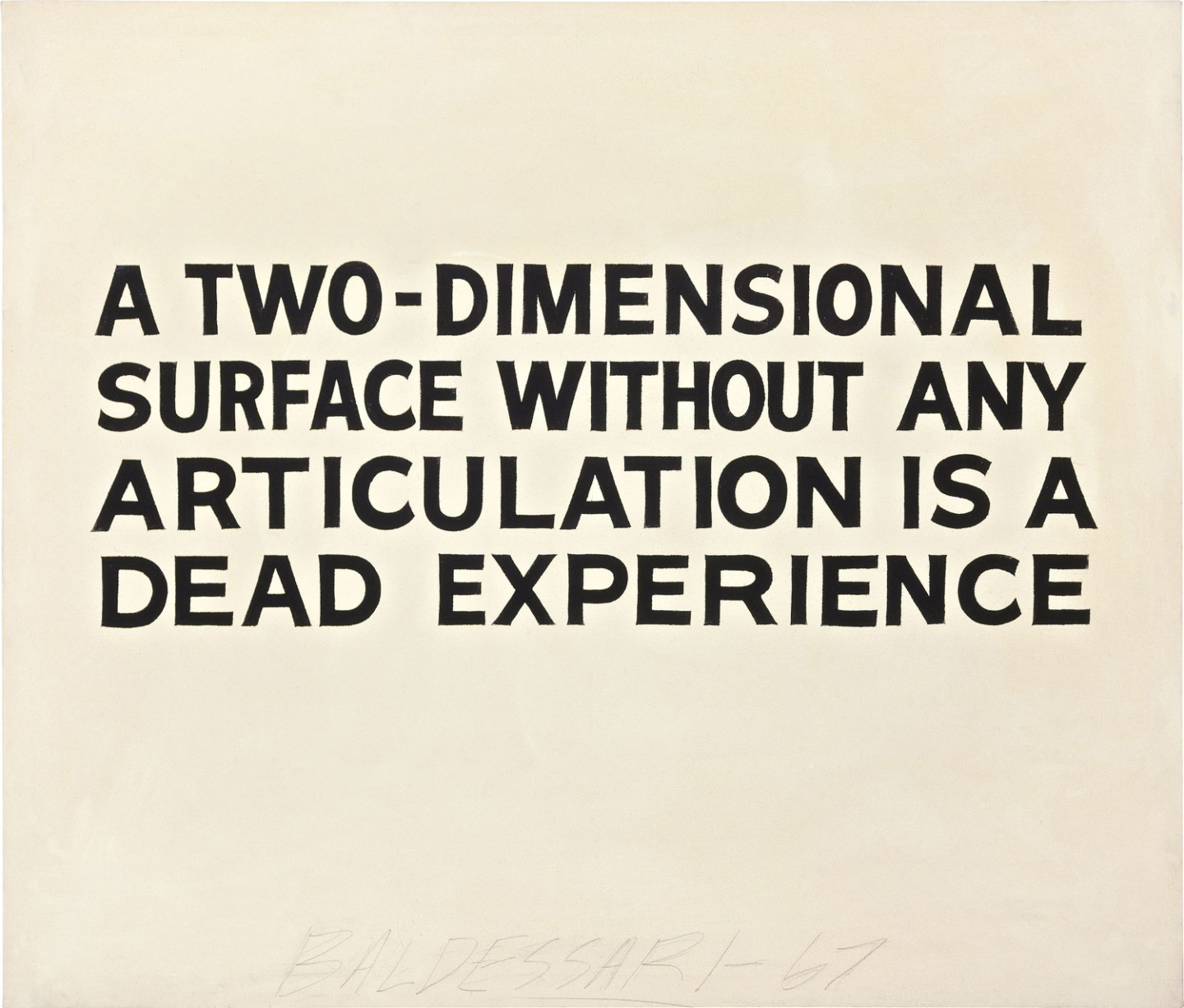

The new approach to text and photography in the mid-1960s also changed Baldessari’s view of his own role as an artist. He continued to define the framework and the contents of the work, but frequently left its execution to others. One such example is one of the earliest works in the exhibition, A Two-Dimensional Surface without Any Articulation Is a Dead Experience (1966 – 67).[2] The work is the first of a number of text paintings on canvases of a standard format for which professional sign painters were hired to write quotes that Baldessari had taken from art theory or handbooks. Language and text became essential tools for Baldessari as for many other artists who at the time strove to focus on the idea behind the artwork, rather than its aesthetic qualities. At the same time the decision to continue using a traditional stretched canvas was a highly conscious choice to signal that these works were also painting on canvas, and thus also art. His pared-down text works became self-referential paintings that, with their use of quotes, highlight and challenge the relation between theory and artistic practice: “Everything is purged from this painting but art, no ideas have entered this work”. Or like in the painting Tips for Artists Who Want to Sell (1966 – 68), whose first point reads: “Generally speaking, paintings with light colors sell more quickly than paintings with dark colors”.

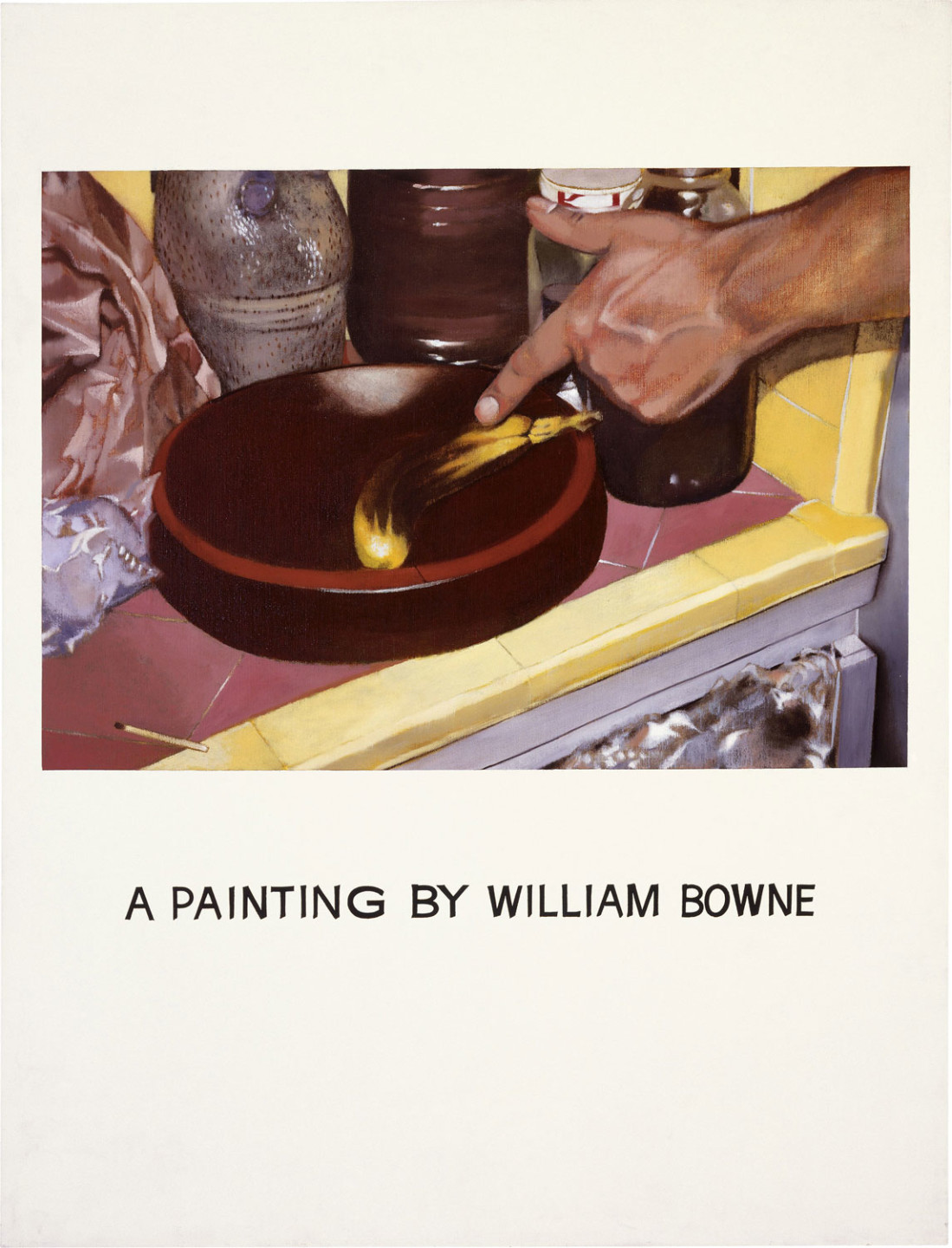

John Baldessari borrowed images and quotes for his works from a variety of sources and found inspiration in different genres that are often located outside the ambit of visual art. Texts on Baldessari often refer to semiotics and the writings of theoreticians such as Ferdinand de Saussure and the structuralist Claude Lévi-Strauss as important influences, as well as film directors such as Jean-Luc Godard and Sergei Eisenstein. The abstract painter Al Held’s critical statement that “all Conceptual art is just pointing at things” inspired the series Commissioned Paintings (1969), for which Baldessari asked a friend to literally point at objects or events that he found interesting, which were in turn photographed. [3] Even here the execution was left to others: a number of amateur painters were commissioned to copy the photographs. Under the different motifs, the text “A painting by”, followed by the painter’s name, can be found – clearly written by a professional sign painter. In the series, Baldessari literally erased all traces of his own hand and even had the works “signed” by other artists. The series can be interpreted as a criticism of abstract expressionism’s notion of the artwork as a direct expression of the artist’s emotional life and genius which dominated the American art scene in the 1950s.

The act of identifying, the selection and the decision-making process is highlighted in several of Baldessari’s works as well as being one of the central themes of this exhibition. In certain cases, the choice has been deliberately left to chance, or, as in Commissioned Paintings, to someone else. In other artworks the decisions are based on certain, often playful, conditions or rules established by Baldessari. In Choosing (A Game for Two Players): Carrots (1971 – 72), the decision-making process becomes the actual subject matter of the work. The first photograph in the series depicts how Baldessari, without revealing his choice to the others present, chooses one of the three carrots that are presented to him. The two remaining carrots are replaced with two new ones, and in the next photograph Baldessari is shown choosing one of the new batch of carrots. During the many times that the situation is repeated, while constantly being photographed, Baldessari starts developing strategies for his choices, which are unknown to everyone but himself. The series of photographs is part of a larger group of work in which the person choosing, as well as the vegetable used, varies, although the rules remain the same. By highlighting and exploring the process of choosing, he demonstrates the subjective aspects of decision-making and how these are applicable to our understanding of art and how we generally view and evaluate art.

In 1970, Baldessari made his arguably most drastic and irrevocable choice. In the mid-1960s, his practice started demonstrating an unmistakable re-evaluation and a new direction. In the text The World Has Too Much Art – I Have Made Too Many Objects – What to Do?, written in 1969, Baldessari listed different alternatives for what could befall his early works – like having them micro-photographed and then placing the miniature photographs under postage stamps on letters that would be sent to friends, or pulverising the artworks and mixing their remains into the food offered at art events. The following year, Baldessari put an ad in a local newspaper announcing that on 24 July 1970 he had cremated all the artworks in his possession made between May 1953 and March 1966. The cremation was documented photographically and the ashes of Baldessari’s “body of work” were collected in a bookshaped urn. The photographs and the urn are now part of the work Cremation Project (1970), which is included in this exhibition. In a text from the same year, Baldessari comments on the work as follows: “Will I save my life by losing it? Will a Phoenix arise from the ashes? Will the paintings having become dust become art materials again? I don’t know, but I feel better”.[4]

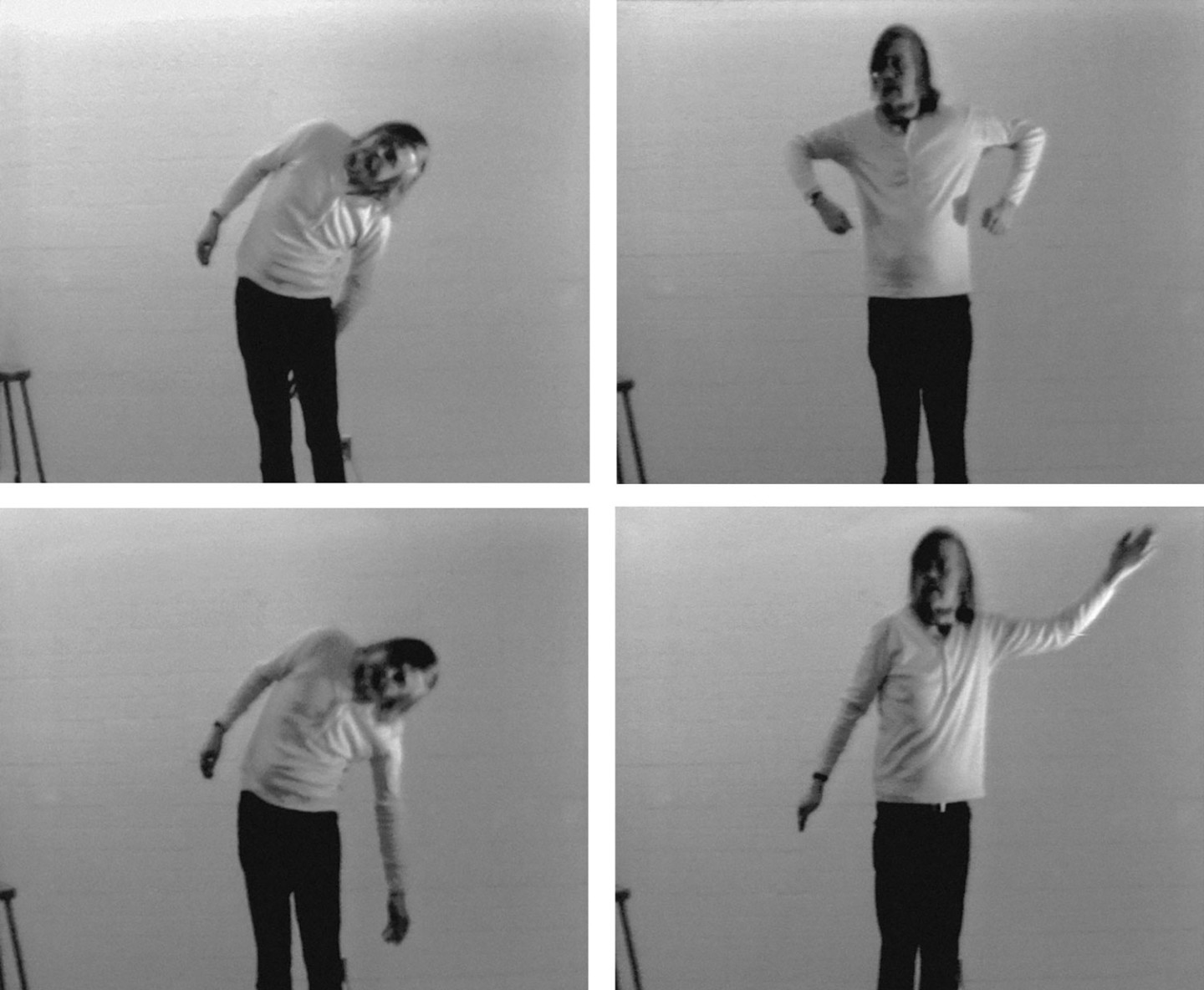

When video was introduced as an art form, CalArts was one of the first art academies to use video cameras in their teaching. Between 1968 and 1977, Baldessari himself made 55 film and video pieces, some of which are included in this exhibition. One of them is I Am Making Art (1971), where Baldessari is seen to be stiffly moving his hands, arms and legs in front of the camera, while repeating the phrase “I am making art” with a variety of intonations. With an underlying tone of both irony and humour, he comments on Conceptual art and the notion that all actions can be art.

Through Baldessari’s questioning of artistic norms, many of his works illustrate what is often overlooked, what exists and occurs on the periphery. Several artworks in the exhibition depict things that are usually considered to be non-motifs, and prevailing rules of composition are challenged: “What I am looking at in photographs is usually the stuff that’s not too ‘interesting’, it’s the stuff you see in out of the corner of your eye, rather than what you normally focus on …” [5] Econ-O-Wash, 14th and Highland, National City Calif. (1966 – 68) is an early such example. The work is part of a series in which Baldessari portrays his hometown of National City outside San Diego on the West Coast of the USA, a place that, according to the artist, was as far as one could get from the avant-garde art scene. The photos were taken from the driver’s seat of the car and Baldessari placed no particular importance on what the camera was directed towards or the composition of the image. The photographs were transferred onto canvases, again employing a professional sign painter to paint the exact address of where the photo was taken under each image. The series conveys an attempt at departing from established ways of seeing and composing images. Suburban environments are reproduced without embellishing descriptions in a way that makes the familiar almost foreign.

John Baldessari likened an artist to a person who can see connections in unlikely circumstances. With time he let the stretched canvases and photographs become the sites of many unexpected encounters under improbable conditions. Here Baldessari brought together images from art history, popular culture and different kinds of texts. The proximity to Hollywood, the centre of power of the film industry, and access to black-and-white stills from film productions that were meant to be destroyed, were an endless source in his artistic practice. The photographs were kept in Baldessari’s image archive, categorized by motif and stored in alphabetical order. During the work process, details are enlarged or painted over. The motifs are combined with other images and sometimes even words, and the new constellations supply further interpretations and meaning. The works become complex collages whose frames in certain cases change format, or disappear completely when the artist lets the shape of the subject matter also dictate the contours of the work. Baldessari described his work as a quest “to find the precise and only word, the right images. And when these atomistic parts collide, powerful meanings can ensue. The job is to discover those meanings that are the most economical while at the same time being the most elegant. And with hope, to agitate and disturb the thought and soul of the viewer”. [6] Baldessari stressed that he was more interested in images, rather than the films per se. At the same time, the fact that the imagery of Hollywood films has found its way into all of our minds like some sort of collective unconscious is something he harnessed in his work.

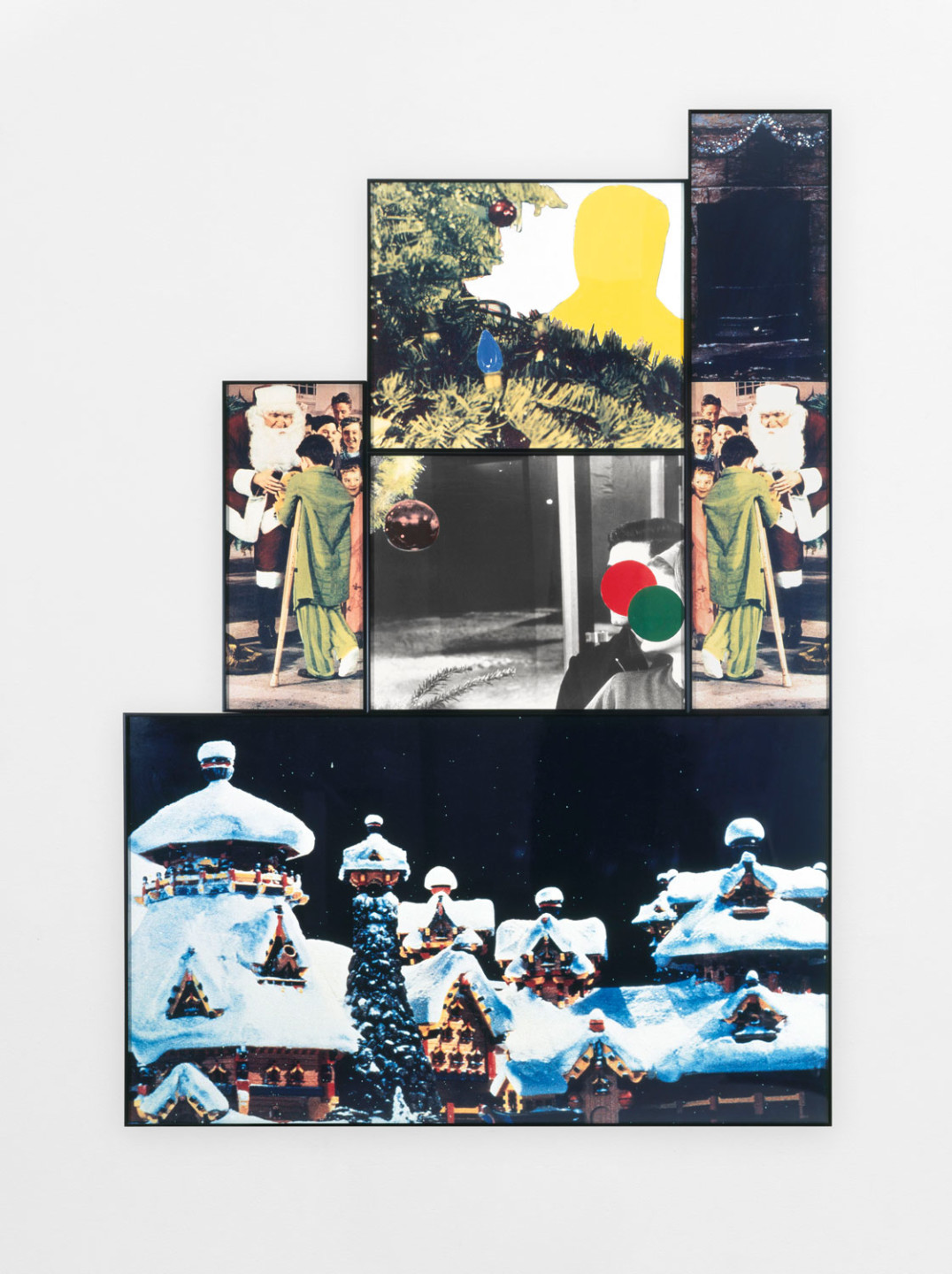

According to Baldessari, the colours of the dots symbolise different feelings: red for danger, green for safety, yellow for chaos or insanity and blue for harmony. By blocking fragments of information, and adding new elements to the pictures, Baldessari creates a tension between what is visible and what is concealed.

In the mid-1980s, Baldessari started painting over parts of the images and eventually hid the faces of individuals behind circle-shaped fields of different colours, so that the characters became anonymous and other parts of the photographs became the focal point. One such example is the artwork Christmas (With Double Boy on Crutches) (1991), which is included in the exhibition. According to Baldessari, the colours of the dots symbolise different feelings: red for danger, green for safety, yellow for chaos or insanity and blue for harmony. By blocking fragments of information, and adding new elements to the pictures, Baldessari creates a tension between what is visible and what is concealed. He himself asserted the presence of absence as one of the essential features of his work. What is left out is more significant than what is shown and he embraced the unrest or discord that the absence evokes.

Baldessari’s early video works also contain elements of dismantling reality, isolating and scrutinizing both its constituent parts and its different narratives, stories, words and images. In Xylophone (1972), Baldessari repeats a word referring to a thing for each letter of the alphabet while holding up a flashcard of a drawing representing the object. Through repetition his words become increasingly abstract and the sound gradually becomes disconnected from its original meaning. The artwork has been interpreted as a commentary on the type of Conceptual art that highlights the distance between the expression of the sign and its content. In the film Title (1977), Baldessari separates components that could potentially all together create a film scene. Gradually colour, sound and sequences with the actions of the actors are introduced, but instead of creating a discernible narrative, Baldessari focuses on the underlying structures, the component parts of the film’s scenes. In parallel with the production of images, Baldessari was a prolific writer. In penetrating, elucidating and humorous texts ranging from instructions and work descriptions to short-story-like narratives (often ending in a moralizing final sentence), a perceptive and astute authorship emerges. This publication feature a selection of Baldessari’s texts. The majority of them have a direct link to works shown in the exhibition, while others provide insight into the artist’s overarching thoughts and ideas about art and creativity. Baldessari’s literary interest is discussed in Ann-Sofi Noring’s text “What We Talk About When We Talk About Art” in this catalogue.

Over more than five decades, John Baldessari continuously examined the relationship between text and image and what emerges when they are brought together. By using and appropriating existing images and texts in his work, Baldessari provoked questions regarding authenticity and the validity of images, questions that are still highly relevant. His work can be described as both consistent and contradictory. The artworks are thoroughly thought-through and unexpected, rule-driven and playful, absurd and accessible. Baldessari’s practice encompasses editing, reducing and compressing. Nevertheless, the works expand beyond the sum of their parts through the slippage of meaning and the new signification that the collision between text and image induces in the viewer. While John Baldessari re-evaluated traditional pictorial conventions and notions of what constitutes art, he primarily challenged our habitual ways of seeing: “My goal has always been to attack conventions of seeing. The work is about seeing the world askew”. [7]

References

[1] John Baldessari, “Allegories, the Connections that Aren’t

so Apparent, Are a Way out of Relational Art” (1982) in

”More Than You Wanted to Know About John Baldessari”,

Meg Cranston and Hans Ulrich Obrist (ed.), Zürich:

JRP Ringier / Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2013, vol. 2, p. 104.

[2] The title is a quote from the Hungarian artist and theoretician

György Kepes’s book ”Language of Vision”, Chicago:

Paul Theobald, 1944.

[3] Al Held, quoted in Coosje van Bruggen, ”John Baldessari”,

New York: Rizzoli, 1990, p. 47.

[4] Baldessari, “Cremation Piece”, (1970), vol. 1, p. 98.

[5] Baldessari, “I Started Out as a Painter, Skowhegan Lecture”

(1993), vol. 2, p. 172.

[6] Baldessari, “Some Notes on Recent Work” (1989), vol. 2, p. 168.

[7] Baldessari, “Photography Changes What Artists Do” (2011),

vol. 2, p. 229.

Matilda Olof-Ors

Matilda Olof-Ors is curator for Swedish and Nordic Art at Moderna Museet. She has among other exhibitions earlier curated Atsuko Tanaka (2019 with Jo Widoff) Concrete Matters (2018), Thomas Schütte: United Enemies (2016), Olafur Eliasson: Verklighetsmaskiner /Reality machines (2015), Georges Adéagbo: The Birth of Stockholm..! (2014), Christodoulos Panayiotou: Days and Ages (2013).

Buy the exhibition catalogue

The John Baldessari introduction is featured in the exhibition catalogue.