Jeff Koons, Michael Jackson and Bubbles, 1988 © Jeff Koons

Introduction

From the rise of abstraction in the first decade of the twentieth century to the post-medium environmental and social experiments of the last, sculpture in the modern period constitutes a gradual undoing of the traditional artform as we once knew it.

Flying in the face of avant-garde orthodoxy, Fritsch, Koons, and Ray would redeploy traditional sculptural conventions, creating discrete art objects that are not only overtly representational, but also frequently figurative. The art on view in Sculpture After Sculpture, then, may come after sculpture’s supposed demise, but it also comes after in another sense, being made after—in the image of—the art form it would reimagine.

The way these sculptors have folded the experiments of the twentieth century into the complex statuary of the twenty-first is the story this exhibition sets out to tell.

Between the church and the shop window

Art’s confrontation with the shop window is a foundational leitmotif of the modern period, and one writ large in a trio of works that highlight the roles of the readymade and Pop art in the parallel evolutions of this show’s protagonists. When Koons’s epochal series The New (represented here by his New Hoover Convertibles, New Shelton Wet/Drys 5-Gallon Doubledecker (1981–87)) debuted at Manhattan’s New Museum of Contemporary Art, it was in that venue’s storefront window on busy Fifth Avenue.

Similarly, Fritsch’s Madonnenfigur / Madonna (1987), a human-scaled blowup of her 1982 multiple, first materialized between, in the artist’s own words “the church and the shop window,” in a public square in Münster, Germany.

Ray would find his own point-of-purchase vehicle in a series of works based on the standard-issue display mannequin. Represented here by his now iconic Fall ’91 (1992), a work conceived in three differently-attired variations, Ray’s commercial clones, like Koons’s pristine vacuum cleaners and Fritsch’s multiple Madonnas, would collapse Minimalist seriality and Pop art repetition, pointing the way beyond the Minimalist moment that preceded them.

From found to made

If the earliest works in Sculpture After Sculpture may still be understood as readymades, they are readymades only in the most radically “assisted” sense. A far cry from Duchamp’s quotation bicycle wheel or inverted urinal, here the found object reappears fantastically fetishized (if not entirely remade), an irony that underwrites a shared evolution in the work of all three artists from the found to the made.

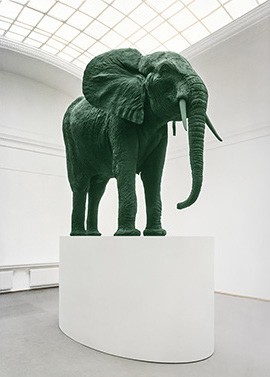

Whether the later works exhibited here are simulations of pre-existing objects (Koons’s glistening monument Balloon Dog (Red) (1994–2000) is based on an ephemeral party favor, while Fritsch’s Frau mit Hund / Woman with Dog (2004) reimagines a tourist trinket made of seashells as a human-scaled confection), or, as in the case of Ray’s The New Beetle (2006), the readymade is replaced with a direct depiction from life, each artwork suggests an obsessive attention to craft.

Abetted by today’s advanced technologies, this perfectionism reaches its mythical apotheosis in Koons’s studio-as-factory, where a team of assistants can be found working round-the-clock shifts. When Ray remarks that he wants us to “hold our breaths” in the presence of the art object, he speaks for all three sculptors.

Sculpture After Sculpture

As each artist internalized the logic of the readymade and moved beyond this gambit, subject matter, long repressed during the reign of abstraction and Minimalism, would make a return, and with it a strong current of allusion to the sculpture of the past, including the deep past of antiquity.

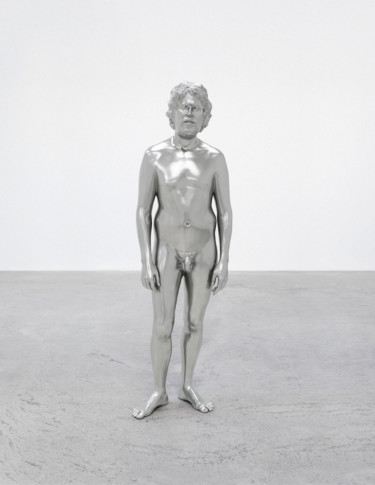

Ray’s Young Man (2012) updates the ancient Greek kouros type as a California hipster, while Koons’s Metallic Venus (2010–12) reimagines the Callipygian Venus of the first century B.C. as glistening lava of turquoise stainless steel.

“Venus of the beautiful buttocks” was inspired by the tale of two sisters who quibbled as to which had the more perfect backside, and here Koons’s metallic goddess has a new competitor, this time a decidedly mortal male. The most memorable asset of Ray’s Young Man may indeed be his rear end, though it must be said that here the attribute captivates us in direct proportion to its distance from the classical ideal!