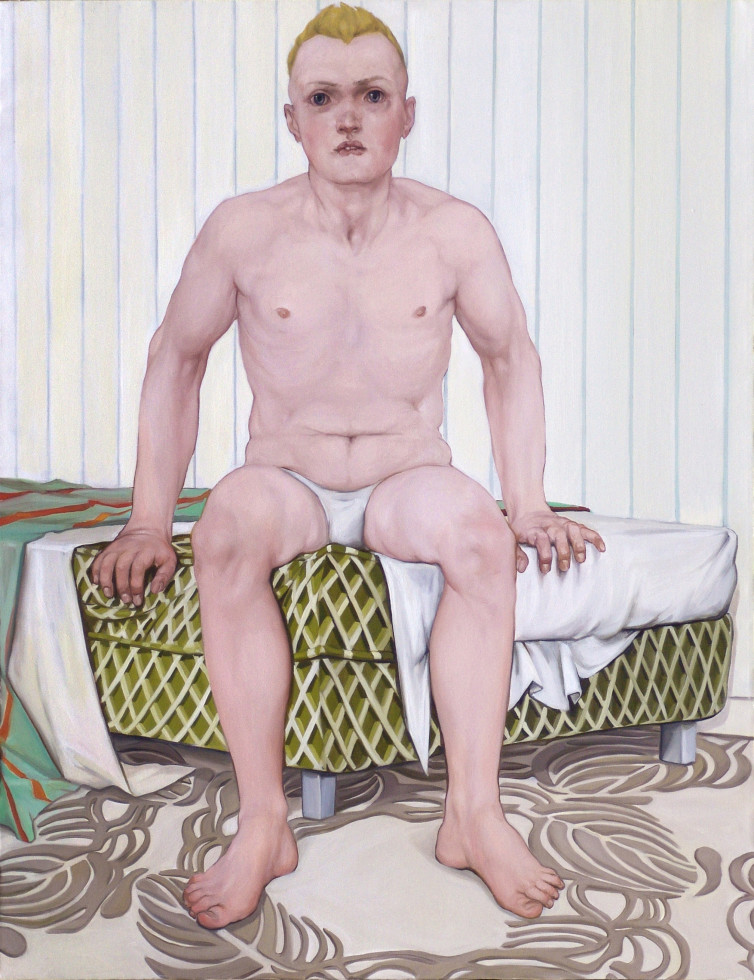

Biljana Djurdjevic, Hanging on, 2006 © Biljana Djurdjevic

The 1st at Moderna: Biljana Djurdjevic

Living in Oblivion

1.12 2006 – 1.1 2007

Stockholm

The eyes are those of the young teenagers in the paintings Living in Oblivion (2006), Hanging On (2006), and Dummies (2006). Something appears to have happened to the children. Perhaps something sinister. They seem to be the victims of some act of cruelty. But we don’t know what. Apart from the eyes and the body language, there are no indications of vulnerability.

It is precisely this uncertainty about what has occurred that makes the paintings interesting. Our mass mediatised world is characterised by various kinds of sensationalism, preferably those that concern children and teenagers. I recognise the eyes in the paintings from newspapers and television. Hardly a day goes by without a paedophile ring or a child labour scandal being exposed somewhere in the world. Are there more paedophiles and more child workers today than before? Or could it be that the mass media is more willing to report from a world that is also shrinking?

Djurdjevic’s paintings form associations with such issues. However, their emotional intensity makes viewing the works an almost physical experience. The eyes get under my skin. How can I understand what has happened, the children seem to be thinking. Silently I stare back. Yes, indeed, how can I understand? Do I want to understand? As an adult, what responsibility do I have for what has happened to them?

The works are sinister. Sad and frightening. Looking at Djurdjevic’s earlier paintings, I understand that she is also expressing different forms of power relations. She employs a painterly approach that cleverly accentuates the relationships and the unpalatable subject matter.

Her earlier paintings, such as Dentists’ Association (1996-98), Cabaret (1999-2000), and The Last Days of Santa Claus (2001) are based on a classical composition technique. In Dentists’ Association, four dentists pose in a surgery, reminding one of Flemish 17th century portraits of professional groups. Cabaret shows four charging cavalrymen, surrounded by barking fighting dogs. The painting displays clear references to Baroque battle paintings while The Last Days of Santa Claus has obviously borrowed its formal inspiration from Andrea Mantegna’s The Lamentation over the Dead Christ from ca 1490. Like Mantegna, Djurdjevic paints with a shortened perspective that creates a deep illusion in the image. But instead of Christ we see a dead Santa Claus lying on a lit de parade with a Christmas wreath under his head.

In her most recent work, for example Living in Oblivion, something has crept in that “disturbs” the well balanced painterly composition. As in early 16th century Mannerism painting, proportions and spatial illusions are perverted. If I look at the painting long enough, I experience a sense of dizziness. The bodies appear to be falling out of the room; indeed, sliding out of the paintings.

Her works touch upon the discussion of how an aesthetic experience can be combined with ethical questions. In John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera from 1728, adapted by Bertolt Brecht into his The Threepenny Opera, one of the characters says, “Murder is as fashionable a crime as a man can be guilty of.” In Brecht’s case, however, the aesthetic experience remained within the area of fiction. Brecht claimed that a newspaper photograph of a factory says nothing about the social, economic or political circumstances of the workers. In order to make such conditions visible one must create theatre.

Djurdjevic, however, complicates things by distorting the illusion. In her earlier paintings, the art historical references are set in contemporary environments, sometimes with absurd results. Cabaret appears to take place in a swimming-bath or a mortuary!? In any case, the bloodthirsty emotions are presented in a cold and clinical environment. The anachronism generates a curious aura in the painting – violence is timeless.

In the series with the vulnerable teenagers, it is, above all, the Mannerist perspectives and the eyes of the children that are central. The violence is not explicit but takes place in my, the viewer’s, imagination. Looking straight into a dark abyss, I am reminded of the19th century writer Thomas de Quincey who said that an artwork about a murder is not a story about murder but murder itself. When looking at a murder scene, the perspective cannot be that of the victim but of the murderer – or the viewer. If one really succeeded in assuming the victim’s point of view, the fear would be so overwhelming that an aesthetic experience would not be possible.

What makes Biljana Djurdjevic’s paintings both uncomfortable and relevant is the fact that she succeeds in combining aesthetics and ethics. There is also a geographical reference. I read in the brutal contemporary history of the Balkans in her paintings. History has wounds that will not heal. But this is also true for the rest of the world.

John Peter Nilsson

The 1st at Moderna is an exhibition programme for contemporary art. The opening is always on the first day of the month, and the exhibitions are in different venues in or outside the museum.