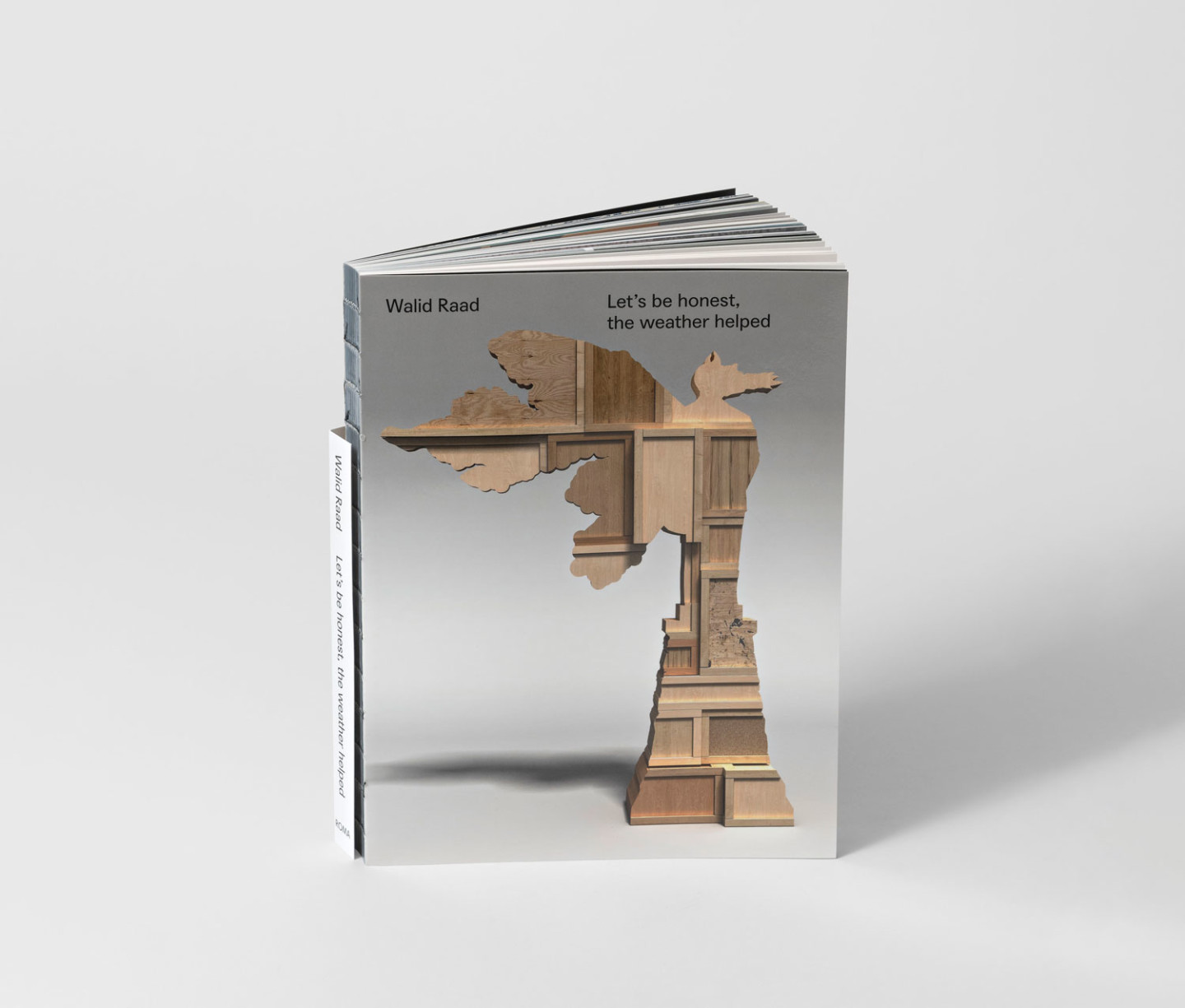

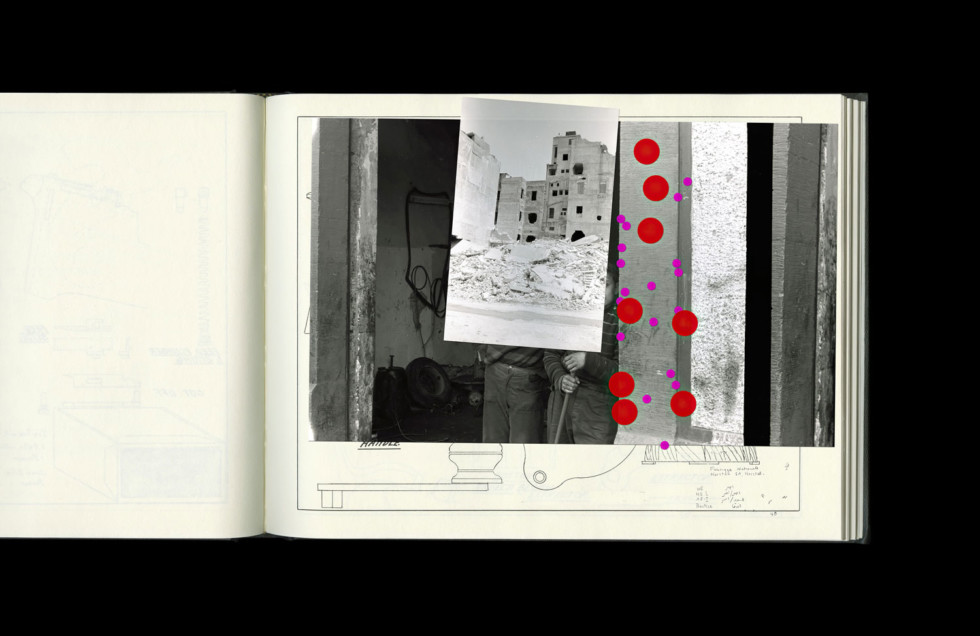

Walid Raad/The Atlas Group, Let's be honest, the weather helped_12 Belgium, 1998, 2006 Courtesy the artist & Sfeir-Semler Gallery Hamburg / Beirut © Walid Raad

Let’s be honest, the weather helped

Text: Fredrik Liew, curator

About halfway through Walid Raad’s most recent walkthrough performance piece ”Kicking the Dead and/or Les Louvres” the artist introduces the story of six historical objects from the collection of the Louvre’s Islamic Art department being sent from Paris to the newly opened Louvre in Abu Dhabi. While unpacking these objects, the museum discovers that the historical treasures have morphed into unrecognizable states. Panic unfolds and when all conventional attempts to explain this tragedy are exhausted, Raad, an artist-in-residence in the Louvre at the time, is allowed to study the artefacts. After spending ten months with the objects, he decides to look at them through so called “extensions”, forms that he finds in historical paintings from Persia and India. Through an elaborate scheme that involves tinting these found shapes with natural colours, finding the right combinations of shape and colour, and looking at the objects through layers of these extensions, Raad manages to see what has actually happened. Like a mise en abyme, this sequence can be understood to represent Raad’s practice and methodology: applying the sensibility, tools, and expertise of an artist to engage in how violence affects bodies, minds, cultures, and tradition. Through the process of observing and researching, he allows himself to be led in multiple directions, making discoveries that he connects through photographs, videos, sculptures, texts, mixed-media installations, and performances.

What if—strange as they sometimes seem—the stories Raad tells us and the documents he creates do not primarily exist to question or counter existing narratives, but actually have a motivated relationship to the history, memory, and geopolitical tensions he is talking about? What if Raad is presenting us, as an artist and in his artwork, with artistic or aesthetic facts that he has actually witnessed?

As in the example above, Raad often proceeds from historical events and arrives at seemingly ludicrous, bizarre, and wondrous situations and documents. How shall we begin to understand the overwhelming ambiguities in these works? While many accounts of Raad’s art emphasize that he engages imaginary and/or fictive dimensions to question and critique how history, memory, and geopolitical relationships are constructed, I would like to propose a parallel departure point. What if—strange as they sometimes seem—the stories Raad tells us and the documents he creates do not primarily exist to question or counter existing narratives, but actually have a motivated relationship to the history, memory, and geopolitical tensions he is talking about? What if Raad is presenting us, as an artist and in his artwork, with artistic or aesthetic facts that he has actually witnessed?

One way of accessing Raad’s practice is through his background in photography. As a teenager, his father helped equip him with a darkroom and access to a few international photography magazines in his home in Beirut. In 1985, two years after Raad’s emigration to the United States in the midst of the Lebanese civil wars, he enrolled in the Rochester Institute of Technology’s photography program, which is renowned for its rigorous technical education. In graduate school at the University of Rochester, Raad complemented his undergraduate training by attending seminars on Marxism, psychoanalysis, linguistics, post-colonialism, feminism, and queer theory, among other subjects. And it was Kaja Silverman’s seminars on Freud and Lacan in particular that opened up a way for Raad to fuse his technical and theoretical knowledge— thereby, I would argue, shaping the foundation of his artistic practice to this day. In Freud’s trauma theory, the event and its consequence have a referential relation but may not be connected by a traceable physical imprint (such as a gunshot wound). Instead, consequences also appear in distorted forms and the patient has trouble naming the events that gave rise to his or her hysterical symptoms. By applying Freud’s theory of trauma and consequence to the process of creating documents of an event, Raad opened up for himself a new understanding of the “documentary.” This idea shaped Raad’s way of addressing historical and contemporary events in his early work with the Atlas Group, which engages with the history of the Lebanese wars. But it also influences key aspects of his more recent work, borrowed from Jalal Toufic, such as labyrinths, ghosts, and vampires—as well as his desire to create a non-subjective model of how violence affects the world.

”Kicking the Dead and/or Les Louvres” is a seventyfive minute performance—a narrated meandering featuring stories of war, death, ghosts, art, the history of tall buildings, free education, ownership, displacement, slavery, financial speculation, and various defence measures employed by the objects and people subject to violence or threats. The exhibition ”Let’s be honest, the weather helped” leans on ”Kicking the Dead and/or Les Louvres” as representative of leitmotifs in Raad’s oeuvre and as a device to disconnect individual works from their previous organization (the long-term projects ”The Atlas Group”, ”Scratching on things I could disavow”, and ”Sweet Talk: Commissions”). Instead, the exhibition arranges Raad’s projects along several key trajectories that run through his entire practice, essentially attempting to form a non-chronological exhibition with a retrospective scope. The succeeding parts of this text follow this ambition.

One of Walid Raad’s ongoing concerns is the significance of locale, particularly how different forms of violence or disruptive events can affect the lives of objects, ideas, or artworks.

In Transit, A Shift of Context

One of Walid Raad’s ongoing concerns is the significance of locale, particularly how different forms of violence or disruptive events can affect the lives of objects, ideas, or artworks.

I chose to depart from the work ”Secrets in the open sea”, which consists of twenty-nine framed blue monochrome photographic prints. At first glance the blue is what meets the eye and as such, the work clearly evokes the Western tradition of pure abstraction in the arts; a formalist or essentialist trajectory that most often is independent of references beyond itself. But we quickly understand that these particular blue fields, presented within the framework of the Atlas Group, are not just blue images. The setting of these works is the Lebanese wars, wherein an individual’s personal political viewpoints are rarely permitted to stand on their own; they are instead hijacked by the dominant political and confessional ideologies. Pure abstraction—if there is such a thing in this context—will always have other meanings. Blue must hide something, must mean something else. So, what does this blue hide? Here and elsewhere in Raad’s practice, the colour blue is connected to the Mediterranean that stretches out from Lebanon’s famous coastline. Of course, during the war, the sea was not only associated with ongoing recreation but also with attempts to flee toward safer territories or with the illegal trade permitted in the emerging militia-controlled ports. Crossing the sea under precarious conditions was—as it still is—a very dangerous act, so in turn the blue also holds narratives of death and the dead. In the wall text that accompanies the work, one discovers that these prints were found buried under the rubble during the 1993 demolition of Beirut’s warravaged commercial districts and were entrusted to the Atlas Group for preservation and analysis. Remarkably, small black-and-white group portraits of men and women were recovered from within these monochrome blues. Upon further investigation, the Atlas Group was able to identify all the individuals and it turned out all of them died in the Mediterranean between 1975 and 1991.

Another example can be drawn from the series ”Sweet Talk: Commissions”. In Commissions (Storefronts: 1987–2005), Raad was hired by one of his cousins, who was active in the local militia, to photograph various storefronts. Proud to have his first professional job as a photographer, he proceeded to make pictures inspired by his favourite artists, such as Eugène Atget and Walker Evans. Years later he found out that his images were used by the militia for unexpected purposes. Owners of these stores had refused to pay the “security fees” imposed on them and consequently they had been beaten or exiled and their businesses confiscated.

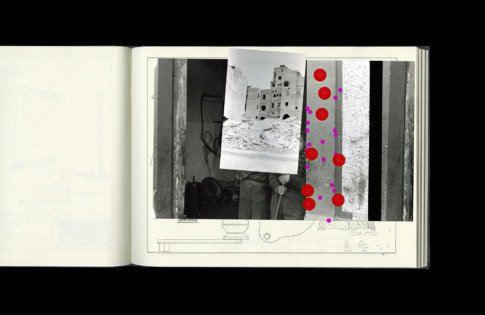

Situations like these, where shifts of locale have radical effects, reverberate throughout Raad’s practice. His own works, for example, were shrunk to 1/100th of their original size when they were exhibited in a white-cube gallery in Beirut’s Karantina neighbourhood, which is one of the most polluted and low-income areas in the city and the site of the 1976 massacre of 1,500 Palestinians, Syrians, Kurds, and others. In ”Appendix XVIII: Plates 22–257” (2008), we learn how colour, lines, shapes, and forms were affected by war. Sensing danger, they “took refuge, camouflaged, or hibernated in Roman and Arabic letters and numbers; in circles, rectangles, and squares; in yellow, blue, and green. They dissimulated as fonts, covers, titles, and indices; as the graphic lines and footnotes of books; they camouflaged themselves as letters, price lists, dissertations, and catalogues; as diagrams and budgets.”

The Louvre Abu Dhabi is a case in point for ”Kicking the Dead and/or Les Louvres”. From Raad’s narration we learn that the museum, designed by Jean Nouvel, is situated on an artificial island they call Saadiyat, which translates to “island of happiness.” Apart from the Louvre, which has already opened, there exist architectural plans by Frank Gehry, Norman Foster, Zaha Hadid, and Tadao Ando for other cultural institutions to be built on this land and complete the cultural tourist paradise, boosting economic growth and the region’s profile as a new cultural and economic centre.

Raad proceeds his performance by addressing the terms of the contract between Abu Dhabi and the French government to build the Louvre Abu Dhabi. His investigation echoes the analyses that were made of the blue photographic prints in ”Secrets in the open sea” and the pivotal question can be formulated in the same way: What is hiding behind the erection of a Louvre in the Arab world?

We learn that the contract has twenty-one articles and three annexes regulating things like the training of staff, conservation methods, and finances. Just to license the name Louvre for thirty years and six months, the French government charged the Arabs €400 million. Raad also tells us that there is a special paragraph in the contract stipulating that there should be no special exhibitions organized during the months of June, July, and August. Why? Apparently, the French curators realized that it is an unbearably hot season in the United Arab Emirates. So, Raad decides to visit one summer and see for himself, only to witness around seven thousand workers sweating twelve to fifteen litres per day in the fifty-degree heat to construct the building.

It is well documented how Dubai and Abu Dhabi have systematically violated the human rights of the many migrant workers employed in erecting its infrastructure. The working conditions have been compared to slavery. One worker described his situation in a 2009 article in ”The Independent” titled “Dark Side of Dubai”: “The work is the worst in the world. You have to carry 50-kg bricks and blocks of cement in the worst heat imaginable. […] This heat—it is like nothing else. You sweat so much you can’t pee, not for days or weeks. It’s like all the liquid comes out through your skin and you stink. You become dizzy and sick, but you aren’t allowed to stop, except for an hour in the afternoon. You know if you drop anything or slip, you could die. If you take time off sick, your wages are docked, and you are trapped here even longer.”

At the other end of this relationship stands the European art world with its vast historical collections and buildings, but also its shrinking public budgets. European cultural institutions, in need of “foreign aid” to maintain and expand their cultural spheres, are now leveraged in geopolitical negotiations. For instance, the Louvre, which houses one of the world’s largest collections of Islamic art, opened a new, re-styled gallery for its Islamic collections in 2012 that was funded in part by Prince Alwaleed bin Talal of Saudi Arabia. According to the ”New York Times”, his twenty-million-dollar donation was the largest single monetary gift ever given to the museum. The oil company Total and the governments of countries like Saudi Arabia, Oman, Morocco, Kuwait, and the Republic of Azerbaijan also contributed, making it clear how the Louvre plays a significant role in international cultural diplomacy.

It goes without saying that the sociopolitical, economic, and human-rights dimensions of all of the above provided Raad with material not only for his artwork, but also for his activism. In 2010, Raad was part of a group of artists, activists, and scholars who started the Gulf Labor Coalition to bring awareness to human-rights violations in the United Arab Emirates and to secure better working and living conditions for the mostly migrant laborers building the Guggenheim and Louvre in Abu Dhabi. This is clearly very important and urgent work, to which Raad and many others continue to be dedicated. But Raad is also cognizant of the distinct possibilities and limitations of what his art and activism permit him and others to do, feel, think, create, and experience. He rarely confuses the two. And in his artworks, Raad is clearly focused on seemingly esoteric, irrational, and bizarre encounters with objects. In his performance, Raad informs us that the contract between the French Louvre and the Louvre Abu Dhabi stipulated that a number of art objects from the collection would be made available to the new Louvre. Six of the objects selected for this journey, as mentioned above, were dramatically affected during transit. Raad’s elaborate use of extensions reveal that these objects—burdened by cultural, financial, and diplomatic pressures and feeling neither at home in Paris nor in Abu Dhabi—decided to take matters into their own hands by deploying a sophisticated defence strategy and literally trading faces with each other. Hence each object unpacked in Abu Dhabi was the combination of two others.

From Subjective to Non-Subjective Objects and Bodies

Objects and bodies have a pronounced presence in Walid Raad’s work, often coming across in even the smallest details. As he greets the audience for ”Kicking the Dead and/or Les Louvres”, he asks us to consider how our own bodies are related to space. “Can you hear me well? In the back, ok?” “Is the temperature alright?” “There was a strange smell when I walked in. Yeah? No? No smell? OK.” When the narrative in Raad’s performance begins he introduces us to Jack, an American Vietnam War veteran who now works as a guide in a World War I museum in Ypres, Belgium. Later in the story it turns out that Jack, for many years, worked as the chief forensic investigator in the Medical Examiner’s office in New York City, collecting, preserving, and packaging the physical evidence of crime scenes. Jack says he hates coming back to New York because everything reminds him of a dead body: pants with a certain pattern, a flower with a certain smell, certain precise colours, specific shapes, an ashtray.

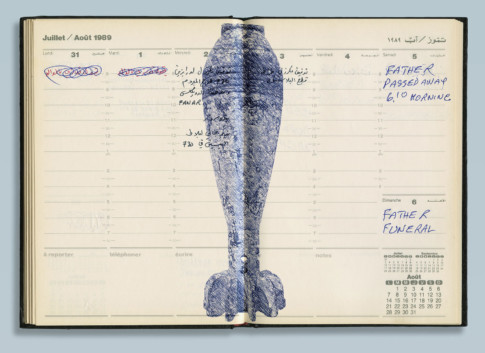

Jack’s relation to these objects and smells reminds of Marcel Proust’s notion of involuntary memories, but also of how objects appear in several of Raad’s early works, where they, when appearing in various documents, come to serve as forensic links and instruments for remembrance. These works often also involve obsession and repetition. One character collects every sunset, another maps every car bomb. It is as if the repetition in Raad’s work is a cross between the norms of conceptual art practice and post-traumatic stress disorder.

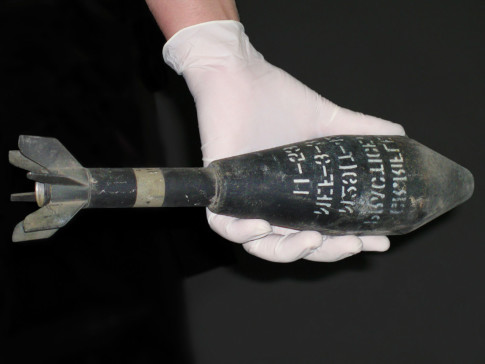

The work that gave this exhibition its title, ”Let’s be honest, the weather helped”, is also based on collecting and mapping objects. As a child in Beirut, Raad went out into the streets to collect bullets and shrapnel, keeping detailed notes of where he found every bullet and photographing the sites of the findings. In those photographs, he covered the bullet holes with dots that corresponded to each bullet’s diameter and the hues found on the bullets’ tips. In the text connected to the work, we further discover that it took him ten years to realize that ammunition manufacturers follow distinct colour codes to mark and identify their cartridges and shells. It took him another ten years to realize that his notebooks serve to catalogue seventeen countries and organizations that supplied the militias and armies fighting in Lebanon. In talking about this work, Raad has explained that he not only has a forensic fascination with ammunition, using it to trace the ideologies and economies behind the war: who invented, produced, sold, bought, fired them, and who was injured or killed. Strange as it may sound, he also has other forms of attraction to these lethal objects. Their shapes, weights, and colours have an emotional pull. And they acted as vessels for yet another kind of connection: “In a way they were the most material manifestations of the war for me. I rarely saw the person actually shooting or actually bombing where I lived. But I certainly got to see and feel, hear, and experience their bullets and bombs directly. The bullets and shrapnel were the closest link to the person on the other side.”

There are many things to unpack here, but, for now, a particular detail in how Raad tells this story is of interest to me. The words he uses to describe the process of developing content from the shrapnel—“it took me ten years to realize this …” and “it took another ten years to realize that …”—echo the words he uses in his new performance when he is allowed to study the morphed Louvre objects. He says he spent two years with these objects in his studio and that sometime around month ten he realized how to proceed. It is as if spending time with objects activates them and allows them to start telling their stories. Now, while the “stories” of objects play a vital role throughout Raad’s career, there is a major discrepancy between the early and the later works concerning how they do so. Objects appearing in ”The Atlas Group” mostly seem to function the way Proust describes. They are in service of the beholder, projecting back to and triggering knowledge, thoughts, histories, and memories. Essentially, they connect to a subjective position in relation to the world. The objects in ”Scratching on things I could disavow” and later works are different. In these art projects, the objects do their own work, they behave or perform as if they had autonomy: they transform, withdraw, hide, camouflage, lose their reflections, and so on. In the transition from ”The Atlas Group” to later works, Raad makes a major leap from a subjective to a nonsubjective model of how violence affects the world.

Raad observes these effects. In ”Scratching on things I could disavow” and ”Kicking the Dead and/or Les Louvres” he speaks from a first-person perspective and offers us his perceptions, doubts, and convictions. It’s as if Raad has a special perceptual organ, one that he trusts and doubts. It is also worth emphasizing that he doesn’t spot these norm-breaching phenomena in his daily life; they make themselves manifest to Raad through the artworks he creates. Is this because the facts artists trust are artistic or aesthetic facts? Just as a scientist comes to “proofs” through scientific facts, and economists via economic facts, and chefs through culinary facts?

Besides Raad himself, several other characters in ”Kicking the Dead and/or Les Louvres” have similar experiences. Hanan is the curator of an art collection in Abu Dhabi. During an encounter with Raad, Hanan tells him her story. Some time ago she had an eerie feeling that something was not right with a group of paintings and carpets that she had recently acquired. She sensed that the modern European masterpieces she bought for the collection were not authentic and noticed they started to behave in unpredictable ways. She was at first convinced there was a reasonable explanation. She called in experts to check the provenance of the works in question, their physical condition, and the quality of their crates. Since no answers could be found and as the situation did not conform to expectations, she ended up questioning her own witness account. Is it in my head? Am I hallucinating, projecting these phenomena? Am I crazy? A sort of reversal of the process of involuntary memories. She went to a neurologist, a psychoanalyst, and a psychic to figure out whether there was something wrong with her. It took years of study and questioning, patiently exhausting every reasonable possibility, before accepting that in instances when the world appears to you in distorted forms it might not mean you are out of your mind. It might just mean that the dominant and conventional ways we “make sense” of the world may not apply in this instance and that another approach is needed. A Sheikh finally explained this to her: “Some artworks die. They don’t physically die, but they die before physically dying. And they do not die in the sense that they rot. They are not physically destroyed, they are not burned, they are not stolen. No. They remain physically intact, but they die. Everyone still thinks that they are alive, but a few get the feeling that something is off.”

On Aesthetic Facts and Space-Time

What can we learn from what happened to Hanan? One thing that becomes clear in the Sheikh’s explanation is that the conventional separation between life and death needs to be challenged. There is something else, something in-between. This brings us back to Jack, the forensic investigator turned war-museum guide. During one meeting he confides in Raad and tells a story about a time he was called to a crime scene to find a man that killed himself on his bed with a shotgun. Angered by the fact that this man killed himself at two in the afternoon, which meant his dead body would be found by his family arriving home from school and work, Jack goes on to kick him. Kick after kick after kick. Raad narrates his words: “And you know what? I don’t care if this man is in heaven, I don’t care if he is in hell, I do not care if he is somewhere in between. I can guarantee you he is still feeling my kicks.” This anecdote is as clear as it is confusing. Jack knows a lot about death. He is a Vietnam War veteran living in Ypres, a landscape in which hundreds of thousands of World War I soldiers are in the ground. He is also a scientific expert in biological death—and even had the authority to declare people deceased. Despite all this, he goes beyond his authority, exceeds the definition of his job. He kicks a dead man, convinced that man will feel the pain.

This in-between space in which Jack and Hanan act is important to understanding Walid Raad’s practice. It is a space beyond established categories, concepts, disciplines, and binary oppositions that have served for centuries as the foundations of mechanistic world views, views that also transform lives into the aggregate of their material components. Needless to say, Raad has little faith in such aggregates and the numerous binary oppositions that prop them up: life/death, rich/poor, hot/cold, West/East, North/South. He is even sceptical of new and more complex models of aggregation, ways of vacuuming and mapping data into dynamic, real-time, layered systems. “Wouldn’t it be comforting,” he says, “if what we needed was just a more complex map? Wouldn’t it be nice if ethical, political, cultural, historical, and scientific problems would just be solved by a more ‘intelligent’ artificial intelligence?” In spatial terms, we can think of the concept of a veil and the implied logic of “unveiling” or “revealing,” as with a stage curtain in a theatre. What Raad tells us is that he does not think of the veil as a device of division. He addresses neither what is in front nor what is behind it. Instead, Raad talks about the veil or curtain itself as a vast space to explore, or alternatively as a lens to look through when studying something.

This notion—of a space in which we might not even grasp that there is one—recurs often in Raad’s works. In 2004 Raad staked out, photographed, and filmed an intersection in the eastern Beirut neighbourhood of Furn El Chebbak. This was the site of one of the more than 3,600 car bombs that exploded in Lebanon during the war. In a project he calls ”My neck is thinner than a hair” (2000–03), Raad looked closely into these particular events. After spending time in this area, talking to people, and trying to forensically map the events, Raad’s cameras were beginning to record things that were significantly different from what he saw with his eyes while shooting. Raad collected this footage for the video work ”We can make rain but no one came to ask”. At first glance, the video seems to show a conventional and coherent street view. But this representation of space viewed with a photographic lens does not seem to correspond to the actual space the people in the film inhabit. As we look closer, cars and people passing by suddenly disappear and then appear somewhere else. In addition, layers of data and architectural drawings begin to superimpose themselves over the landscape on the screen.

In conversation, Raad explained that, when all this started to appear in his recorded material, he didn’t know what was going on. But he also said that he recognized these spatial phenomena from earlier in his life, that they had exposed themselves to him during the war. In the early 1980s, Raad was living in a neighbourhood in east Beirut where—as in many places—car bombs and other detonations went off far too often. Every day brought a new explosion. It was obvious that the state couldn’t guarantee citizens’ safety and it was also clear that neither could the local militia that had replaced the state. People started taking things into their own hands, developing their own logics. In order to be safe you needed to know everything about your neighbours, so in a building or on a block people started to get very close, to constantly reveal all their secrets to each other. Did the neighbour’s daughter have a boyfriend or girlfriend? Was he/she going to visit that day and was that perhaps the car downstairs on the street? People started to open up to each other in unprecedented ways in order to confess their innocence before any crime had been committed. Space became different. People started to see through walls; divisions such as public/private or inside/outside began to rupture. In attempting to avoid the next car bomb, people also began shifting behavioural patterns from day to night, thereby also changing the conventional notions of time. Time was no longer something systematic, regular, and shared but something individual. Like ghosts, people started to operate in a different space-time logic than we are accustomed to, as if they were in a labyrinth. And since this logic only prevailed within a limited space, these labyrinths multiplied next to each other all until the city’s fabric consisted of a series of autonomous space-logics operating independently.

What Raad’s experiences in Beirut teach us is that alternative logics are not metaphors; they are facts in the world. So, did Raad enter someone else’s labyrinth at Furn El Chebbak? Whether or not this was the case, what we discover in Raad’s footage is primarily the out-of-synch success/failure of the photographic equipment to provide what was expected. And this is just one of a series of disjunctures; time and again Raad has experienced how conventionally photographing Beirut proves to be a knotty mission.

By considering the possibility of an elastic notion of time and space we are able to begin understanding aspects of Raad’s work that otherwise risk seeming quite mysterious and/or metaphorical, as when shadows disappear, or objects do not appear in mirrors.

The invention of high-speed photography and the “decisive moment” was a consequence of mechanistic world views. Coming out of experiments in the chemical industry’s search for synthetic colour, this more sensitive photographic film, which provided the ability to capture ever smaller slices of time, cemented our understanding of time itself: essentially a series of moments, all the same and succeeding each other in a linear fashion. But what if the world is not in tune with “photographic time,” just like it wasn’t in the early years of photography, when the world had to patiently adapt to exposure times of several minutes in order to register on film? Perhaps what Raad found out was that Beirut’s space-time simply does not correspond to abstract photographic time.

”Sweet Talk: Commissions (Solidere: 1994–1997)” suggests as much. The video shows the demolition of buildings in downtown Beirut after the war in order to make way for a new, strictly planned and regulated city centre. The footage mirrors itself and repeats so that the buildings endlessly go down and up, down and up, down and up. Did Raad edit the video in this way to talk about some kind of metaphorical resurrection? He told me no. Once again, we need to approach this as a literal work and assume that what we see is actually happening to the buildings. What concept might help explain this? Perhaps the buildings are caught in their own time and even when the area is physically rebuilt it will be haunted by this logic. Perhaps people with a certain sensitivity will see this and we are lucky enough to be provided access through Raad’s art. Perhaps it doesn’t make sense, is not referential today, but must be recorded in the hope that it one day may again be referential.

By considering the possibility of an elastic notion of time and space we are able to begin understanding aspects of Raad’s work that otherwise risk seeming quite mysterious and/or metaphorical, as when shadows disappear, or objects do not appear in mirrors. Perhaps it is not that the objects lack substance or that there is no mirror image, the nearest available explanations according to our normal space-time logic. No, maybe it is just that we exist in a different dimension than the objects and therefore the mirror reflections are not available to us at present. Objects moving or acting by themselves are another example. Are they alive and do they have agency? It could be. But it could also be that time is different. Consider that, due to some natural force, the object has moved very slowly over ten thousand years. Maybe it appears to be moving because this long time period is compressed into the blink of an eye? Is this also why Raad insists on placing works like ”Preface to the ninth edition: On Marwan Kassab-Bachi (1934–2016)” on wallpaper and not on the museum’s white walls, to invoke another museum space-time logic that predates the hegemony of white-cube galleries?

In his art, Walid Raad draws our attention to what he calls the symptoms of how violence affects the world. Judging from this exhibition they seem to be piling up. Raad found Hanan, he found Jack, he found paintings without shadows, paintings hiding behind other artists’ works, and the morphed Louvre objects. What these symptoms might add up to, in terms of a world view, Raad does not expressly say. Our first impulse might be that the artist is crazy and needs psychological help—after all, paintings don’t just lose their shadows. This rationalization occurs when we hear a witness’ experience that does not match a dominating “truth.” But one can also start accepting aesthetic facts, something consistent with experience, without knowing how and why, and then look for confirmation: more symptoms, support in other artists’ works or in literature, in someone else who narrates similar experiences. Throughout his performance Raad looks at us intently, as if asking: Is it only me? Am I making this up? Is this all in my head? Does anyone else here see this? Please tell me.

Fredrik Liew

Fredrik Liew is Head of the Curatorial Team and Curator of Nordic Art from 1973 in Moderna Museet, and curator of the exhibition ”Walid Raad: Let’s be Honest, the Weather Helped”.

Buy the exhibition catalogue

Walid Raad’s biographies are published in the richly illustrated exhibition catalogue. The exhibition catalogue also features an introducing essay by curator Fredrik Liew and an interview with Walid Raad by the art historian María Minera, as well as the artist’s complete manuscript to the performance ”Kicking the Dead and/or Les Louvres”, published for the first time.