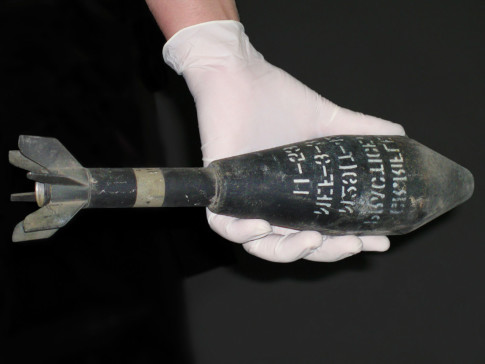

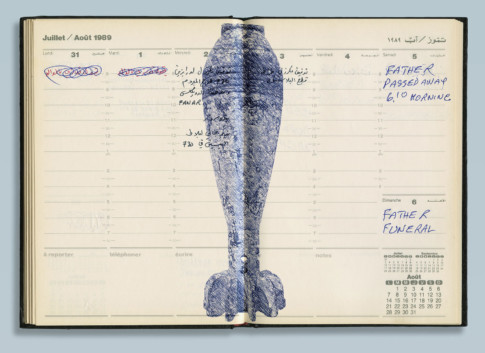

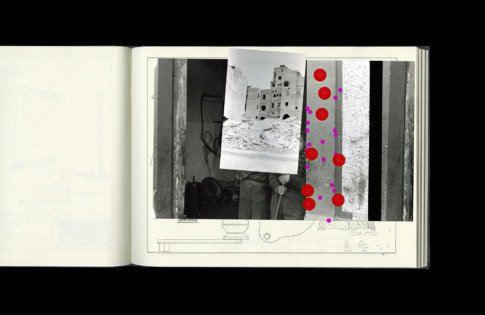

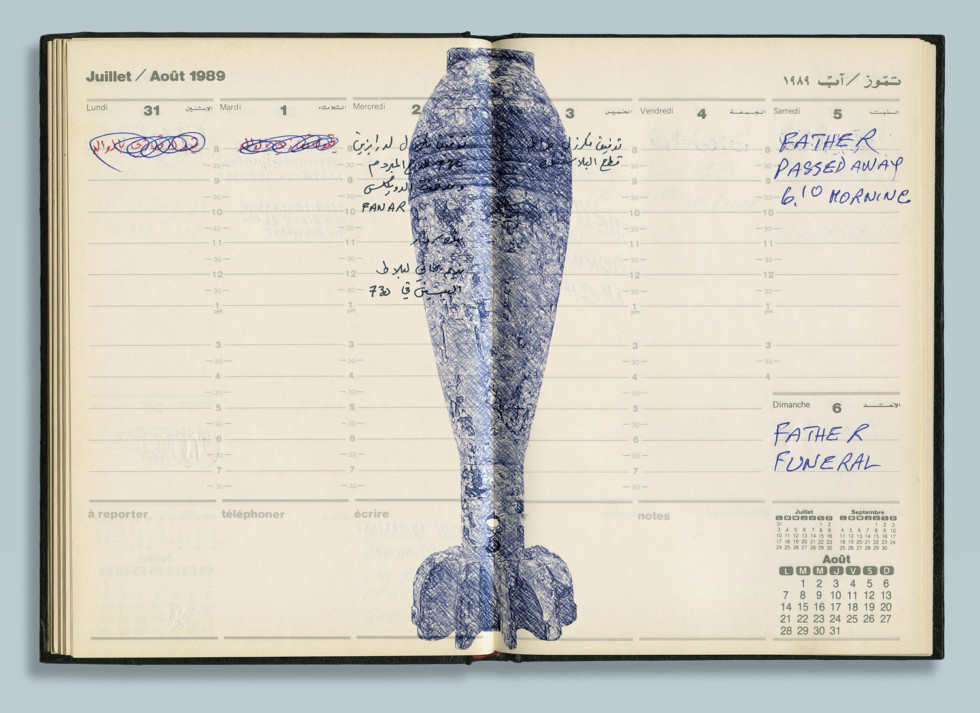

Walid Raad/The Atlas Group, I want to be able to welcome my father to my house_July 31-5,1989, 1990/2018 Courtesy the artist & Sfeir-Semler Gallery Hamburg / Beirut © Walid Raad

Biography Walid Raad

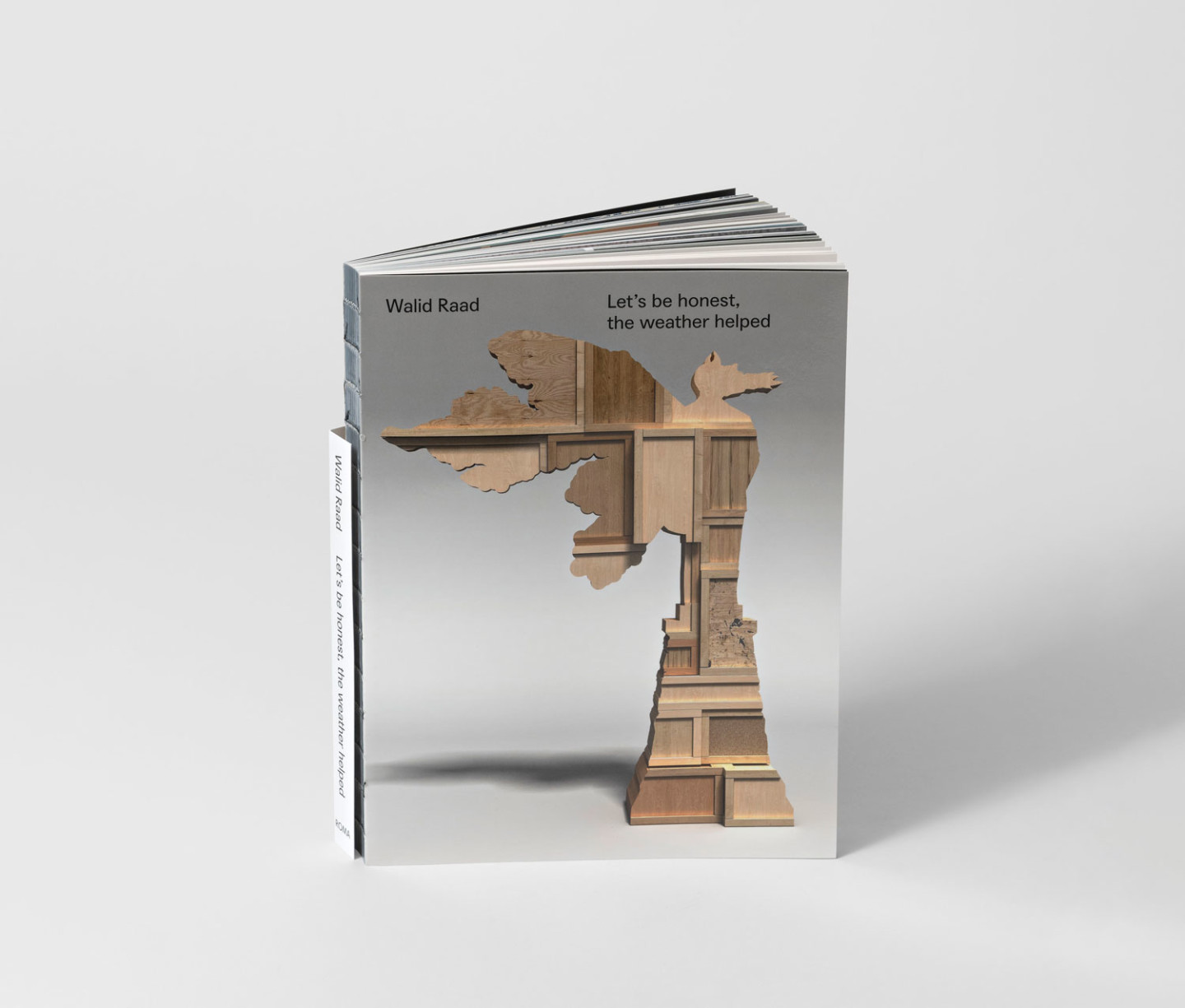

Buy the catalogue in the Shop at the museum, or online: Moderna Museet’s webshop

Biography (#17)

A few years ago, I was asked by the artist and scholar, Gregory Buchakjian, the following questions:

Where did you grow up? Neighbourhood? Village? Individual house or apartment building? Did you go to school by car? School bus? Walking? Did you have to cross through checkpoints or dangerous areas on your way? How was it at school? Were you brave? Were you popular among classmates? Did you keep your schoolbooks? Where you afraid of shelling? Car bombs? Kidnapping? Do you consider yourself to be traumatized? What happened with your collection of bullets and shrapnel? Did you parents bring you to the racetrack? Do you have a particular memory of going to the doctor’s? (Personally, passing in front of AUBMC was much more traumatizing than Murr Tower or Holiday Inn.) Did you prefer going to the beach or to the mountains? Did you like fast food? Rock ‘n’ Roll? Star Wars? Do you have memories of travelling through Beirut International Airport? Cyprus? Damascus? Were you nostalgic for Lebanon when you left? In America, were you Lebanese or American or a migrant? How did you decide to become an artist? Have you ever faced a “choc artistique”? How did you encounter the people who became the postwar artists and thinkers? Jayce Salloum? Jalal Toufic? What about this unusual figure, Lucien Samaha, you interviewed for Ibraaz? Did you know Ashkal Alwan when it started in Sanayeh and Sioufi gardens as sculpture exhibitions? How did you perceive your relationship with this group? You were being published and exhibited alongside them often while living in the US and most of them were in Beirut. Was the fact of being based outside the theatre of operations beneficial for your work?

In the meantime, if we had to put things back on track, we have a series of dates:

1967: Your birth.

1975: Start of the Lebanese war (you are eight years old).

1983: Your departure from Lebanon (you are sixteen) and settlement in the US.

1999: Your participation at “Building City and Nation: Space, History, Memory and Identity,” organized by Samir Khalaf at AUB and Order of Engineers and Architects of Lebanon, July 1–3, 1999.

2008: A History of Modern and Contemporary Arab Art: Part I, Chapter 1: Beirut (1992–2005), at Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut July 17–November 7.

To which I answered:

I suppose that I can begin by adding a few more personal dates and to contest others:

1915: The locust attacks in Syria and Palestine kills hundreds of thousands. My paternal grandparents lived through these events in Chbanieh and remembered them well.

November 2, 1917: The Balfour Declaration is released.

June 15, 1928 or 1929: My father’s supposed birth date. (This is in pre-independence Lebanon and is uncertain since his parents [and whoever was in charge in the mountains during the Mandate period] did not accurately record the mountain inhabitants’ birth dates.) He was born at home, sometime in the middle of June, in the late 1920s. Years later, when he is issued his first identity card, someone wrote down June 15 as his birth date.

June 15, 1967: The birth date listed on my birth certificate. My mother wanted my birth date to coincide with the (uncertain) birth date of my father’s.

1940 or so: My grandparents take my father out of school. He attended school for only three years and was then put to work at age ten. The memory of the 1915 locust attack had traumatized the mountains’ inhabitants. They feared a similar fate with the beginning of WWII. Thus, all hands were on deck. Years later, this affected our family in direct and indirect ways.

June 6, 1967: I am born nine days later, in the midst of the defeat of Arab forces.

1969: Princeton University Press publishes Henry Corbin’s ”Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn Arabi”. I am introduced to Corbin and Ibn Arabi via the books of Jalal Toufic. I subsequently teach a seminar with Toufic in Berlin, as part of Anton Vidokle’s United Nations Plaza, in 2006.

1947–48: The first Arab-Israeli war. My Palestinian maternal grandparents flee Birzeit and settle in Beirut. My mother is a toddler. She grows up in Lebanon.

Sometime in the 1950s: My father is a labourer in Saudi Arabia.

Sometime in the coming ten years: My first trip to Saudi Arabia.

1939: Walter Benjamin writes “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire.” Fifty years later, in Beirut, I will read it along with Proust’s ”A la recherche du temps perdu”, Bergson’s ”Matter and Memory”, Freud’s ”The Interpretation of Dreams”, and Baudelaire’s ”Les Fleurs du Mal”.

1991 and 1993: Station Hill Press publishes the first editions of Jalal Toufic’s books ”Distracted” and ”(Vampires): An Uneasy Essay on the Undead in Film”. I meet Jalal in Beirut in 1992 during my year-long stay there working with Jayce Salloum. I try to read his books in the early 1990s. Throughout the decade, I return to Jalal’s books and cannot enter them until I read a passage in one of his essays on ruins. I am convinced that he is describing an experience I related to him, except that I had not, and he had written the passage in question years before I met him. I commit myself to reading Jalal more seriously and do so until I cannot find my own thoughts without going through his. This state has not yet passed.

1905: Freud’s ”Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality” is published. Eighty years later, Jean Lapanche and Jean-Bertrand Pontalis’s ”Life and Death in Psychoanalysis” is published. I read both books in the late 1980s or early 1990s in Kaja Silverman’s seminars on Freud and ideology at the University of Rochester.

Sometime in the 1960s: My father goes to work in Monrovia and Sierra Leone. He works there throughout the decade and settles back in Lebanon in the early 1970s, most likely in 1973.

1975: Start of the civil war? Or do we set equally contested and loaded dates for the beginnings of the war (restricting this to the twentieth century): 1910, 1914, 1915, 1916, 1920, 1943, 1947, 1967, 1973, 1974?

1975: My first photography class. I can still smell the chemicals in the first darkroom I ever entered.

1977: My first camera: A 35-mm Minolta XG-1.

1981: I read a photo-essay about AIDS in America in French ”Photo”.

1856: William Perkin synthesizes mauveine.

1913: Fritz Haber’s synthesis of nitrogen is manufactured industrially by Carl Bosch at BASF.

April 1915: Fritz Haber supervises the use of gas in western Flanders. His additional inventions will include Zyklon A, precursor to Zyklon B, which will kill millions of Jews and others in Europe during WWII, including Haber’s family members.

1978: I remember wanting to become a photojournalist. I remember walking around and photographing in Achrafieh after the Syrian Army’s brutal bombardment of the Eastern quarters of Beirut.

1983: Hard for me to separate 1983 from the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and its subsequent effects on Lebanon in general and my life in particular.

June 1982: I remember photographing the barbaric Israeli bombardment of West Beirut. I remember photographing it from a parking lot in front of my mother’s house in East Beirut.

Early 1982 and thereafter: A form of mandatory military service is put in effect in the Eastern quarters of Beirut. Many high-school-age boys are forced to serve in the Lebanese Forces, the Christian right-wing militia that controlled where I lived.

1983: War of the Mountain. Boys and men living in areas controlled by the Christian militias and whose families originated from the Metn and Chouf areas are asked to contribute to the Lebanese Forces’ efforts (in alliance with Israel) to “liberate” the land from Syrian forces and their Lebanese allies. Various family members volunteer or are forced to enlist. It is only a matter of time before I am sought. I decide to leave Lebanon. I can leave Lebanon because my family had the means to send me abroad and I had a visa to the US. Why was I granted a visa to go to the USA in 1982? That’s a matter for another time.

I could keep going but I feel that I need to stop and give you a chance to ask a question or make a comment. Or you can ask me the same questions again and I can actually try to answer them this time.

Biography (#31)

Walid Raad is an ______ and an ______ (______, ______). Raad’s works to date include ______, ______, ______ , ______, and ______. Raad’s recent works include______ and ______.

Raad’s works have been shown at ______ (______, ______), The ______ Biennale (______, ______), The ______ (______, ______), The Museum ______ (______, ______), ______ (______, _______), and numerous other museums and venues in ______, ______, and ______. His books include ______, ______,______, and ______. Walid Raad is also a member of ______ (______ , www.______.org).

Raad currently lives and works in ______ (______, ______).

Biography (#57)

Walid Raad a.k.a Dahlia Egad

Born, 1969, in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Currently spends most of her time in Ascona, Switzerland.

Defying classification, Dahlia Egad’s fierce individualism informed her enigmatic and highly acclaimed body of work. Her astonishing diverse works of the past 25 years are amongst the most compelling images of late twentieth and early twenty-first century art.

Her first stage, her theopathic period, was between 1982 and 1991. This was the time she spent traveling between Andalusia and Persia, experimenting with forms, techniques, and materials. The second period of her career reflected the influence of Lucia Fa Jolt, the Persian philosopher of the Imaginal. It was during this period that she witnessed the great religious festivals that have been celebrated since the ancient periods. She began to associate the intuitive aspect of art with the essential element in the popular magical art of the hidden and the unknown.

In 1994, Dahlia Egad began constructing her multilayered, complex wall-relief sculptures. These threedimensional constructs use a pioneering technique of stretching fragments of recycled organic forms of great depth. This technique created unusual depth, forming what she refers to as “the mysterious passions.” The technical handling of her chosen materials stemmed from her early career as a molecular editor. Both her parents were skilled technicians—her mother working in a World War II submarine factory wiring transmitters and her father having invented the first chemical database.

Biography (#131)

Walid Raad a.k.a Suha Traboulsi

Was born in Birzeit (Palestine) in 1943. She moved to Beirut in 1949 and currently lives on Cape Cod, Massachusetts (USA). She studied art at the Beirut College for Women and at the School of Visual Arts in New York from 1962–65, and also at City College of New York from 1967–69. After that she took up philosophy at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After a sojourn at the University of Heidelberg (Germany) from 1972–76, she completed her doctorate in 1978.

After beginnings in painting and following her encounter with the conceptual works and writings of Farid Sarroukh, Traboulsi began to turn her attention to language. She looked into aspects of time and space in an extensive series of works involving texts and numerical combinations on paper. She combined these conceptual investigations in her ”Antithesis” series (1968–70). Traboulsi’s first solo exhibition was the mail art project ”Two Untitled Projects” (1969), which was published in the magazine ”0 to 9” (edited by Vito Acconci). She was the only Palestinian woman artist to participate in important exhibitions such as ”Concept Art” (1969) in Leverkusen (Germany), or ”Information” (1970) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. By this time she had decided to pursue an academic study of philosophy, as she did not feel content with a lay person’s approach to philosophical doctrines.

Traboulsi first gained national attention in the Arab world in the 1970s as an influential and often controversial figure in the Amman, Cairo and Beirut art, performance and conceptual art movements. Once ironically termed the “witch of contemporary art,” Traboulsi achieved notoriety with her sensationalist performance work, in which she investigated the psychological experience of personal danger and physical risk.

Biography (#137)

In part, an artist and a Professor of Art in (the still-charging-tuition, and the school should stop doing so now before yet more debt burdens more students who are not the ones who mismanaged the school’s finances—its Board of Trustees and administrators did so for decades [check out the lawsuit against the Board]) The Cooper Union. The list of exhibitions (good, bad and mediocre ones); awards and grants (merited, not merited, grateful for, rejected and/or returned); education (some of it thought-provoking; some of it, less so); publications (I am fond of some of my books, but more so of the books of Jalal Toufic. You can find his here: jalaltoufic.com), can be found online.

Buy the exhibition catalogue

Walid Raad’s biographies are published in the richly illustrated exhibition catalogue. The exhibition catalogue also features an introducing essay by curator Fredrik Liew and an interview with Walid Raad by the art historian María Minera, as well as the artist’s complete manuscript to the performance ”Kicking the Dead and/or Les Louvres”, published for the first time.