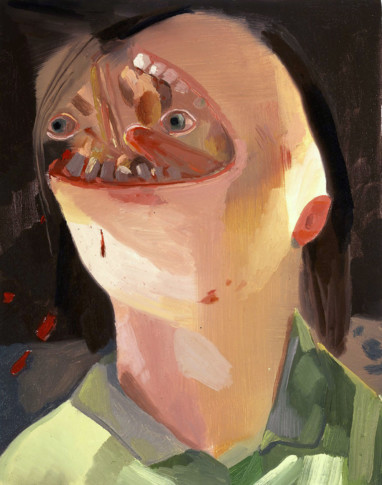

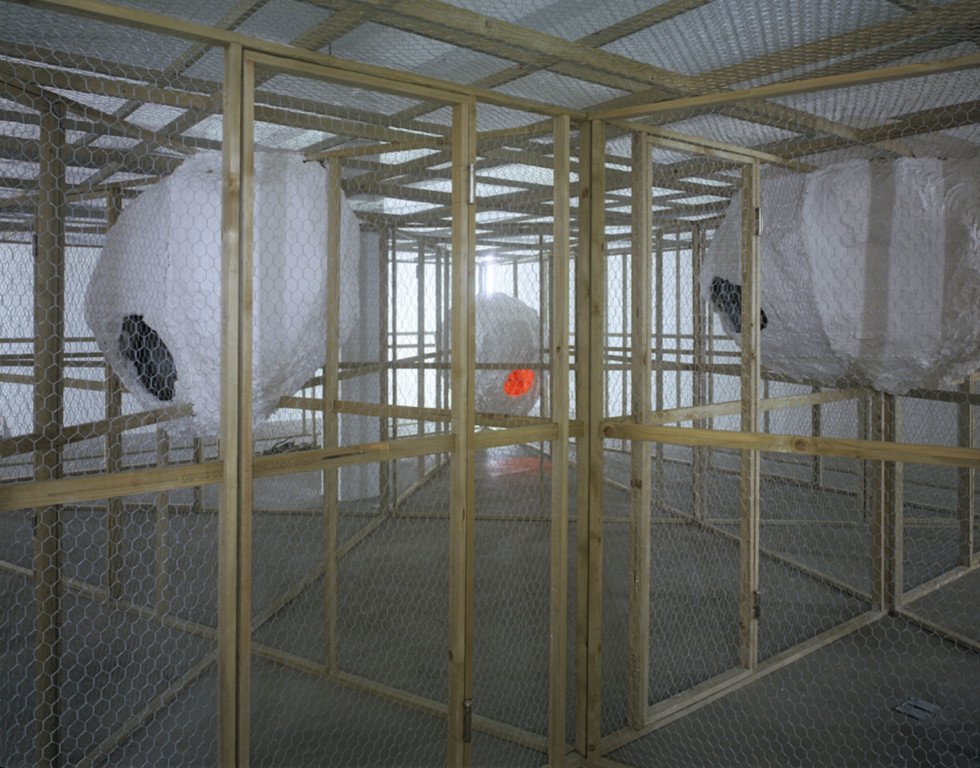

Mike Nelson, AMNESIAC SHRINE or Double coop displacement, 2006 Installation. Moderna Museet. Donation from Moderna Museets Vänner. Courtesy of Matt´s Gallery, London and Galleria Franco Noero, Torino

Mike Nelson

In the mid-1990s, just after Nelson had graduated from art school in London, he invented the biker gang Amnesiacs, an imaginary group of Kuwait veterans suffering from amnesia. Using this gang as his alibi, Nelson gave himself permission to work fictively and intuitively at a time when art was dominated by theory and documentary strategies. For some years, the Amnesiacs “helped” Nelson to create works that were reconstructions of their fragmentary memories.

This strange collaboration resulted in remarkable site installations, which, in turn, prompted Nelson to produce works consisting of several rooms, built so that it was easy to lose one’s bearings. The physical locations, for instance, warehouses, basements, nooks and crannies, became metaphors for inner spatiality: memories, thoughts and feelings. For visitors, this meant having to reconstruct the “reconstruction” in one’s head. For although Mike Nelson’s works can be said to consist of narratives, they lack any background information or text – apart from the title. Instead, the narrative is borne entirely by the information provided by the rooms and objects, giving the viewer generous scope for interpretation.

As a rule, Nelson’s installations contain a plethora of objects but never any direct human presence; on the contrary there is a very tangible absence. The works bear oddly realistic traces of activities, thus disqualifying the settings as pure stage sets. There is dust, dirt, fingerprints on the wallpaper around the light switch, and so on. As one steps into a work, it is almost with a feeling of trespassing on a suddenly and perhaps only temporarily abandoned place. After a while, one easily forgets that one is looking at art, having been seduced by the narrative structure, embraced and absorbed by the constructed environment – as in a story by Jorge Luis Borges, H.P. Lovecraft, Stanislav Lem or the brothers Strugatsky. Although Nelson does not use the written word in his works, literature is nevertheless a rich source of inspiration.

Mike Nelson’s works are often installed in exhibition spaces but sometimes also in places outside the traditional art venues. This usually generates a dialogue with the place or adds a layer of history on top of the existing environment. At the Istanbul Biennale in 2003, Nelson created the work MAGAZIN, Büyük Valide Han. In a historic but long-neglected part of the city he built an installation in the form of a darkroom where hundreds of photographs were hung to dry on lines above the heads of the visitors. The black-and-white images turned out to be pictures of the building and the surrounding neighbourhood the visitors had desperately been struggling to traverse in their search for Mike Nelson’s elusive contribution to the Biennale.

The Amnesiacs biker gang went into hibernation after only a few years’ service with Nelson, but is now back to help him construct the work shown in Eclipse. Amnesiac Shrine or Double Coop Displacement is both like and unlike his previous works. Unlike, in that it is comparably more terse, more transparent and minimal. The basement areas, corridors and rooms have been replaced with a labyrinthine cage made of wood and chicken wire. Yet, all the requisites are there: the spatiality, the labyrinthine claustrophobia. Through doors hidden in the chicken wire we can enter the construction and navigate to the middle of the pentagram that the spaces appear to outline. There are also a few hollow capsules, lit from within, and scorched sticks scattered on the floor.

Where Mike Nelson’s previous installations felt alive in a familiar way with their distinct traces of human activity, Amnesiac Shrine is more like a pared-down sign. He has reduced the work as far as possible without forfeiting its essence, which could also be the definition of a consecrated place. Something is worshipped here, but what? And are the members of the Amnesiacs aware of it themselves, or is this just an incomprehensible image of vague and disintegrated memories? In this flirt with occultism, Nelson continues to play in a narrative space that suggests a voyage or escape into an alternative universe.

But Amnesiac Shrine or Double Coop Displacement is also a sinister reminder of presence, here and now. The structure of the two cages is modelled on Bruce Nauman’s Double Steel Cage from 1974, one of his works that encourage visitors to enter into rooms and situations where we have physical experiences and “understand” the works via our bodies. To enter into Amnesiac Shrine is not pleasant. Intellectually, the transparency of the work ought to allay the claustrophobic feeling. But being able to see what you are separated from and realising that the people outside the cage can watch you paradoxically enhances the barrier between outside and inside.

Fredrik Liew

Mike Nelson

Born 1967. Lives and works in London

Education

1992–1993 MA Sculpture, Chelsea College of Art and Design, London

1986–1990 BA (Hons) Fine Art – First class, Reading University, Reading

Selected solo exhibitions

2007

A Psychic Vacuum, Creative Time, New York, NY [US]

2006

Lonely Planet, ACCA, Melbourne [AU]

AMNESIAC SHRINE or Double coop displacement, Matt’s Gallery, London [GB]

After Kerouac, Centre d’Art Santa Monica, Barcelona [ES]

2005

Spanning Fort Road and Mansion Street – Between a formula and a code, Turner Contemporary, Margate

Selected group exhibitions

2007

AMNESIAC SHRINE or The misplacement (a futurological fable): mirrored cubes inverted with the reflection of an inner psyche as represented by a metaphorical landscape, Turner Prize, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool [GB]

The Pumpkin Palace, Basel Art Fair, Basel [CH]

Breaking Step – Displacement, Compassion and Humour in Recent British Art, Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrad/Belgrade [RS]

2006

The Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin [IE]

Selected bibliography

Peter Eeley, “Looking Back: Significant solo shows 2005”, Frieze, Issue 96, January–February, 2006

Mike Nelson: Between a formula and a code (utst.kat./exh. cat.), Peter Eeley, Richard Grayson, Ralph Rugoff, Rob Tufnell, Turner Contemporary, Margate, Cologne/Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2005

Mike Nelson: Triple Bluff Canyon (utst.kat./exh. cat.), Jeremy Millar, Brian W. Aldiss, Museum of Modern Art Oxford, 2004

Magazine, Bookworks/Matt’s Gallery, London, 2003

Extinction Beckons, Jaki Irvine, Matt’s Gallery, London, 2000