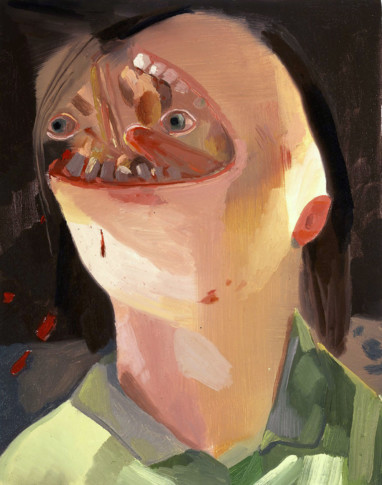

Anri Sala, Med förbundna ögon, 2002 Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Zürich London, Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris, Johnen/Schöttle, Berlin, Cologne, Munich

Anri Sala

The sound is missing and to reconstruct the contents Anri Sala uses a deaf interpreter who can lip read. When his mother is confronted with what she once said she can hardly believe that those are really her words. The film oscillates between documentary and reconstruction or fiction. Since the viewer can see quite easily that some of the scenes are constructed or prepared – for instance, when the artist finds the box with the film – an uncertainty arises concerning the authenticity of the more realistic scenes.

The film Dammi i Colori (2003) also has a documentary style, skimming the surface of the political situation in Albania, while the questions it poses about, for instance, utopias are just as relevant beyond Albania. In the film, Edi Rama, an artist who has been appointed mayor of the capital Tirana, describes his idea of painting the house fronts in the city in bright colours, a project that has been partially implemented. The strong colours made a visible difference in the city, while promising that other changes were possible and would come in the future. In an interview, Anri Sala has described how words such as “absurd” and “surrealist” have come into use among the middle classes in many former east bloc countries to describe reality, while the same words in the west are used to denote other, more exotic or absent realities.

More recent films by Anri Sala have a more minimalist, less narrative, structure; sometimes they only feature a straight-forward scene shot with a static camera. As in Uomodoumo (2000), where the camera films a solitary man in a church. The man is seated in a pew and appears to be about to fall asleep. His head is nodding and he jolts it upright now and then. The quality of the film, the light and the distance to the man make it hard to say whether this is a homeless person seeking a moment’s rest in the church, or whether his overcoat is actually elegant and we are watching a person in an entirely different social position. As in Intervista the information provided to the viewer is insufficient to interpret the images. Jacques Rancière identifies this lack of information or interpretative difficulty as a persistent theme in Sala’s oeuvre.

The title of Anri Sala’s solo exhibition at Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Entre chien et loup (Between Dog and Wolf), alludes to the half-light of dawn and dusk, when it is hard to tell the difference between a dog and a wolf – the “wolf hour”. Anri Sala’s films are often set in this half-darkness, but the uncertainty about what we are actually seeing is also metaphorical and does not relate only to the lighting. It forces us to sharpen our perception and thus forms a starting point for a really good work of art.

Animals feature in many of Sala’s films. They are also in the dark, in the sense that they have a highly limited understanding of their own predicament and the world created by man. In the video Ghostgames (2002) we see two people engaged in a game on what could be assumed to be a beach in the dark. The point of the game is to use torch light beams to lure crabs into crawling between the legs of one’s opponent – thereby scoring a goal.

In Time after Time (2003) a scrawny horse standing by the roadside becomes visible in the light beams from passing cars – every time a car passes the horse lifts its hind leg, but it remains in the same place. The camera focus shifts between the horse and the background, apartment blocks with a few lights burning in the windows. It is easy to imagine that the horse is frightened or paralysed by the proximity of the cars and their headlights, or perhaps it is just sleeping. Again, it is hard to know based on what we see in the film. When the crabs react to the light they seem stressed out, like the victims of a cruel game. In both films the light is artificial, created by machines and by man’s desire for civilisation and enlightenment – while the animals, which are one with nature, react with fear and incomprehension. But we cannot be sure they experience it in that way. Perhaps this is merely the viewer’s projections, one possible interpretation among many.

Magnus af Petersens

Anri Sala

Born 1974. Lives and works in Berlin.

Education

1998–2000 Filmregi/Film Directory, Le Fresnoy. Studio National des Arts Contemporains, Tourcoing [FR]

1996–1998 Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs (section video), Paris [FR]

1992–1996 BA, Painting and Sculpture, National Academy of Arts, Tirana [AL]

Selected solo exhibitions

2005

Lond Sorrow Fondazione Nicola Trussardi, Milano/Milan [IT]

2004

Entre chien et loup/When the Night Calls it a Day, ARC Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris [FR] Turné till/Travelled to: Deichtorhallen Hamburg, Wo sich Fuchs und Hase gute Nacht sagen, Hamburg [DE]

2003

Anri Sala, Kunsthalle Wien, Wien/Vienna [AT]

Selected group exhibitions

2007

Il tempo del postino, Manchester International Festival, Manchester [GB]

2005

Time Zones, Tate Modern, London [GB]

2003

Utopia Station, Biennale di Venezia, Venedig/Venice [IT]

1999

After the Wall: Art and Culture in Post-Communist Europe, Moderna Museet, Stockholm [SE] Turné till/Travelled to: Museum Ludwig, Budapest [HU], Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin [DE]

Selected bibliography

Mark Godfrey, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Liam Gillick, Anri Sala, London: Phaidon Press, 2006

Anri Sala. Entre chien et loup/When the Night Calls it a Day (utst.kat./exh. cat.), Musée d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, Cologne/Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2004

Anri Sala (utst.kat./exh. cat.), Kunsthalle Wien, Wien/Vienna, 2003

Anri Sala (utst.kat./exh. cat.), De Appel Foundation, Amsterdam, 2000

Mark Godfrey, “Missing Presences”, Parkett, Zurich, no 73, 2005, s./pp. 73–78, ill.

Lynn Cooke, “From Silence to Language and Back Again”, Parkett, Zurich, no 73, 2005, s./pp. 58–66, ill.

Jan Verwoert, “On the Margins of History”, Parkett, Zurich, no 73, 2005, s./pp. 86–93, ill.