Nathalie Djurberg, The Rhinoceros and the Whale, 2008 © Nathalie Djurberg

Nathalie Djurberg

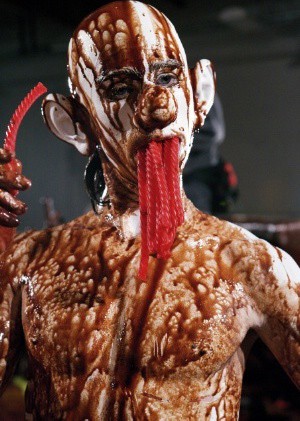

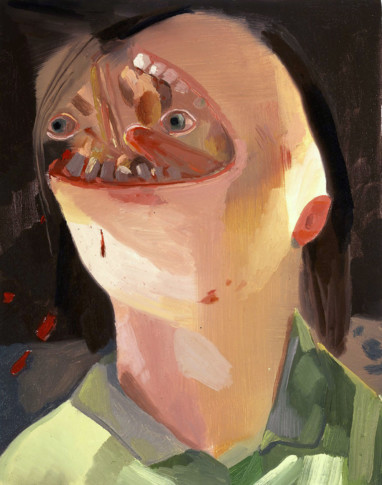

Breton’s opinion that humour liberates and raises us was an essential aspect of the surrealist approach to the utopian potential of art to create a better and more beautiful world. The humour in Nathalie Djurberg’s films can also be both dark and absurd. At first, everything seems straight-forward and innocuous. The animated figures are made of plasticine and they move around in drawn or crudely built sets. The format is similar to that of children’s TV programmes and there is an undeniable feeling of being a child again as we watch. The world is vast and contains exciting new things.

Nathalie Djurberg

The Rhinoceros and the Whale, 2008

© Nathalie Djurberg

Courtesy Zach Feuer Gallery, New York, Gió Marconi, Milano/Milan

Soon, however, we realise that the exciting new things have a dark and threatening side. Girls playing among bright flowers suddenly start fighting with each other, and the man who is playfully jostling the girls more and more intrusively is brutally assaulted, and in another film two girls are drowned in excrement. Animals figure too, not always as cuddly toys but also as untamed or treacherous creatures. The Fairytale world is torn asunder by violent brutality and angst. It is about loneliness and man’s sometimes absurd behaviour. But it is also about war, fear, insecurity and sexuality. About death.

Her films are also about social injustices. But where, on the scale of political correctness, do her works fit in? That is by no means unambiguous. We are increasingly being bombarded in more and more media by sex and violence in every conceivable and inconceivable shape and version. Entertainment is merging with information. Politics becomes drama. Drama becomes politics. On the one hand, we are brought up to be active citizens by keeping ourselves informed about current global events. On the other, we can no longer structure or differentiate between truth and lies, right and wrong, reality or fiction. Everything is for sale. It is hard to defend ourselves, to protect our lives, in such an environment.

I suspect that there is a great deal of Nathalie Djurberg herself in these films. It’s Nathalie against the world. She processes her own despair and fear – and lives out some of her own secret fantasies … the sardonic humour in her films creates a detachment to the serious subjects. The sudden shifts between laughter and anguish remind us of Freud – humour becomes a form of insubordination, a refusal to give in to social prejudice.

Djurberg’s works touch on the discussion on how aesthetic experiences can be combined with ethetic issues. For Bertolt Brecht, the aesthetic experience was, above all, found in the field of fiction. As he himself said, a newspaper picture of a factory, for instance, says nothing about the workers’ social, economic or political situation. In order to illustrate these conditions one must create theatre.

The fairytale world is an especially congenial instrument for telling about complex human behaviours. The films explicitly criticise various kinds of bullying and the assaulted or exploited always win in the end. But the humour and the fable ensure for instance, that the violence in Djurberg’s films is never explicit. On the contrary, it takes place in the viewer’s own imagination. The 19th century author Thomas de Quincey claimed that murder as a fine art is not the story about murder but the murder itself; in other words, the presentation of an event is given a greater value than the original event. In consequence, the perspective when regarding a murder cannot be that of the victim, but must be that of the murderer – or the onlooker. If we were able to assume the position of the victim, our fear would be so overwhelming that an aesthetic appreciation would be impossible.

That is probably why Nathalie Djurberg’s films are both entertaining and disturbing, private and general – giving satisfaction and producing pain. Their ambiguity makes them elusive. The works balance between hope and despair. The tension puts me constantly on guard and makes me impervious to it all. Ultimately, therefore, it concerns my refusal as a human being to be ringed or controlled.

John Peter Nilsson

Nathalie Djurberg

Born 1978. Lives and works in Berlin

Education

1997–2002 MFA, Konsthögskolan i Malmö/Malmö Art Academy, Malmö [SE]

1995–1997 Hovedskous Målarskola/Hovedskous Art School, Göteborg/Gothenburg [SE]

1994–1995 Folkuniversitetet, Grundkurs i konst/Basic Art Education, Göteborg/Gothenburg [SE]

Selected solo exhibitions

2008

Nathalie Djurberg, Fondazione Prada, Milano/Milan [IT]

2007

Nathalie Djurberg – Denn es ist schön zu leben, Kunsthalle Wien, Wien/Vienna [AT]

Nathalie Djurberg, Färgfabriken, Center for Contemporary Art and Architecture, Stockholm [SE] (Årets Beckerstipendiat)

Nathalie Djurberg – Den 1:a på Moderna, Moderna Museet, Stockholm [SE]

Selected group exhibitions

2008 The Puppet Show, ICA Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, PA [US], Santa Monica Museum of Art, Santa Monica, CA [US], The Contemporary Museum, Honolulu, HI [US

] 2007 Performa 07 – The Second Biennial of New Visual Performance, Performa, New York, NY [US]

2007 Fractured Figure – Works from the Dakis Joannou Collection, Deste Foundation for Contemporary Art, Aten/Athens [GR]

2006 Into Me/Out of Me, P.S.1, Contemporary Art Center, Long Island, NY [US]

2006 Rings of Saturn, Tate Modern, London [GB]

2006 Of Mice and Men – 4th Berlin Biennial for Contemporary Art, Berlin [DE]

Selected bibliography

Germano Celant, Nathalie Djurberg, Fondazione Prada, Progretto Prada Arte, 2008

Natahlie Djurberg: Denn es ist schön zu leben, Kunsthalle Wien, Verlag für moderne Kunst (Taschenbuch), 2007

Nathalie Djurberg. Carnegie Art Award 2008, Carnegie Art Award Publishing, 2007

Nathalie Djurberg, Traum &Trauma – Werke aus der Sammlung Dakis Ioannou, Athen, Kunsthalle Wien, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2007

Nathalie Djurberg, Eros in der Kunst der Moderne, Fondation Beyeler, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2006