Korakrit Arunanondchai & Alex Gvojic, Songs for living, 2021 © Korakrit Arunanondchai. Courtesy of the artists and Bangkok CityCity Gallery, Bangkok; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; C L E A R I N G, New York/Brussels; Kukje Gallery, Seoul/Busan. From the exhibition catalogue Korakrit Arunanondchai – From dying to living, Moderna Museet & Verlag der buchhandlung Walther und Franz König, 2022.

Between Ghost and Machine

The exhibition “From dying to living” is a personal contemplation of the movement between worlds, a composition that simmers with expressions and avoids ingrained conceptions. Ghostly companions take us through the teeming material of the video installations, in which documentary pictures from within crowds protesting in the streets or from places loaded with historical trauma are combined with suggestive stagings of collective rituals. Political movements and conflicts are woven together with the artist Korakrit Arunanondchai’s own experiences of love and loss. In an environment of dampening, tactile materials, such as textiles, water, and earth, we are surrounded by the sound-image. As viewers, we are swept into a multifaceted narrative that, like streaming water,appears to be searching for a path out, away from the physical space.

Korakrit Arunanondchai works with videos, installations, music, and performances. He sees himself primarily as a storyteller, finding inspiration in geopolitical history, folklore, and different modes of collective gathering. His works contain moments of seduction – in the poetic language, the overwhelming visuality, and the music. Here, there is both an immediate sense of recognition, as well as the experience of stepping into something incommensurably otherworldly. Arunanondchai’s themes resound with dualities – spirituality and technology, subject and collective, memory and amnesia, contemplation and ecstasy. Throughout, there is a recurring dissolution of the sense of identity, in regard to generations, gender, and nationality. He works from an experience of betweenness, as someone born and raised in Thailand but now based in both Bangkok and New York. His family history, too, is characterized by an experience of transnationality, with both Chinese and Thai ancestry.

Korakrit Arunanondchai’s production develops horizontally, in serial projects where each idea and expression stretches into the next, without consideration of material nor medium. The titles of his works also develop shoots and mutate into new variants or number series, until the disparates rather emphasize a feeling of symbiosis. The way in which each work cycle is given fuel and direction likens a living assemblage, in which a mycelium of materials and ideas expands into what seems like a self-generating system. Recurrent collaborators come and go from Arunanondchai’s work within a setting for socially oriented practice, which consciously problematizes ideas about authorship, and which does not differentiate the process from the finished art object.

In a series of works from 2014–2015 that revolved around the artist’s persona as “denim painter”, denim was introduced as ground instead of canvas, and also a stage to gather around. Today, denim is an almost generic material, which has, at the same time, a problematic colonial history. This blue gold, the indigo-colored cotton cloth with its five-thousand-year-old roots in Indian textile tradition, was traded by Arab merchants and renowned in ancient Greece (where they did not have a word for the unusual color, something that is also true of classical Chinese and Japanese). The secret behind this plant pigment first became known in the West through Marco Polo, and this eventually led to mass production in the colonies, made possible through slave labor. This durable cloth was developed for large-scale production by weavers in Nîmes in France and then exported to the United States. Today, denim is a staple product that is distributed globally, not least back to the original lands where it was produced, but now with the addition of complex cultural and socioeconomic codes, which span from the working class and subculture to haute couture and fetish.

Buddhism and animism permeate Thai culture and philosophy, while at the same time, Arunanondchai shows that these cultural foundations are employed to underpin completely new national narratives, with the aim of undermining democratic development.

A recurring theme in Arunanondchai’s work is the blending of animism and technology, in which elements of Thai folk beliefs can take the form of high-tech, connected applications. “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” as the British scholar and author of science fiction Arthur C. Clarke said, about the potential of both categories to fulfill our dreams*. In the video work “Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3” (2015), the main narrator, Chantri, modeled after the symbol of the bird god, Garuda, has a key role as a drone, which personifies the regime of order, surveillance, and control by the ruling state. Meanwhile, their arch-enemy, the magical water serpent Naga, who rules the underworld, has become in Arunanondchai’s work a stand-in for the state of formlessness. Buddhism and animism permeate Thai culture and philosophy, while at the same time, Arunanondchai shows that these cultural foundations are employed to underpin completely new national narratives, with the aim of undermining democratic development. Spirits recur in his work as metaphors for repressed trauma and suppressed history. The artist himself takes the role of a spirit-medium, a mediator in the transition between the past and now, life and death.

Several works contain references to “ghost cinema”, a phenomenon from Northeast Thailand, where films were shown on portable 16 mm projectors by American troops, who were stationed in the jungle there during the Vietnam War, and also by propagandists, who traveled between villages. The screenings were sometimes used as psychological warfare, to frighten the local population and to keep them at a distance. In time, Buddhist monks in the area also began to project films against the temple walls to please the spirits, as votive offerings. Tall tales were spread about how the serpent god Naga himself enticed people to arrange these spirit screenings, nang kae bon, in isolated areas where there are portals that connect worlds*. The filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul has reflected, regarding how perceptions about the specificity of spiritual places in Thailand can affect both the shooting of a film and the finished product: “There was a ritual influence in how we shot particular scenes and how I sought to evoke certain feelings. Especially when you shoot in the dark. With this knowledge of spirits or ghosts that surround you, you have to pray before you shoot, every day […] This is the effect of the space and the location, and it enters right into the work*.”

For Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Arunanondchai has explored the transcendent layer between worlds, merging two of his existing video installations, which constitute polar opposites in the exhibition.

Even in his early works, Arunanondchai incorporated personal experiences and family history. His maternal grandparents, with whom he was close, became both characters and subjects in material in which he worked with audio-visual memories and the potential to have endless repetitions of video loops, as a way of jointly processing their developing dementia. Through his maternal grandfather, an experienced diplomat who had been posted to a number of key countries, Thailand and Southeast Asia’s political history comprises a natural background for other narratives. In the three-channel video installation “No history in a room filled with people with funny names 5”, which was shown at the Venice Biennale in 2019, the international media spin about the lost boys in the Tham Luang cave in 2018 became a focus. Three of the boys, from the peripheral borderland with Myanmar, were in fact stateless, but after the rescue operation, they were hastily and publicly awarded citizenship by a regime that recognized that the election was getting closer*. In Arunanondchai’s work, passage through the cave or the forest is attributed to the transformational power that is found in both Eastern and Western traditions – we leave the place changed, transformed.

For Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Arunanondchai has explored the transcendent layer between worlds, merging two of his existing video installations, which constitute polar opposites in the exhibition. “Songs for dying” (2021) is immersed in a political theme, with a depiction of the peaceful demonstrations for democratic reform, and against the army and the King of Thailand, which broke out and were forcefully shut down in Bangkok in 2020. Significantly, the hand gesture from “The Hunger Games” was employed by the demonstrators in a blending of reality and popular fiction*. Against these contemporary uprisings and expressions of violence, there are photos from the island of Jeju in South Korea, where a massacre took place in 1948, during which the army murdered thirty thousand civilians. This brutal attack, wrongfully labeled as anti-Communist, followed significant popular opposition to the US’s initiative of dividing Korea into two nations. The death of the artist’s grandfather is also central to this work, as it constitutes a broken link in the understanding of the Cold War’s consequences in the region, as well as in Arunanondchai’s own family history. Documentary photos of grief work are braided into a stream of different materials, footage that was mainly edited during the isolation of the pandemic. The video is shaped like a song cycle, divided into sequences with different music and protagonists, where sometimes it is unclear whose voice we are hearing. Parallel with this personal leave-taking, the narrative is carried further by a dying turtle, an animal that has a strong mythological connection as the progeny of the sea god and that also plays an important role in the legend of how the historical kingdom of Korea arose.

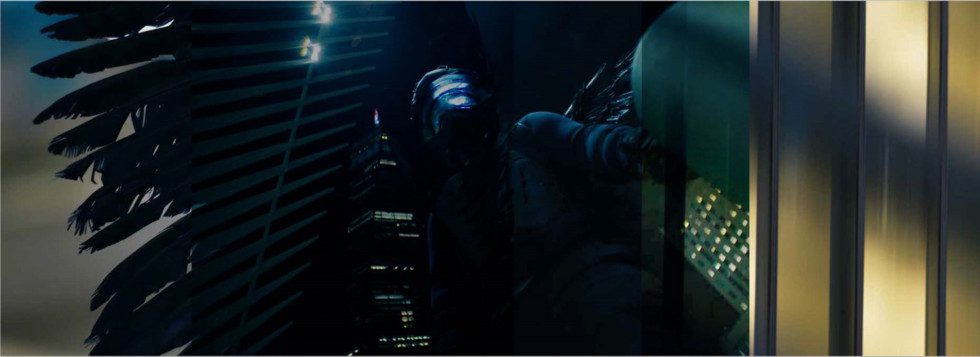

The second video work, “Songs for living” (2021, with Alex Gvojic), depicts collectivity and togetherness in a narrative form, with music and poetry read by the vocalist Zsela*. Angels dressed in black with scorched wings, conspirators on a mission, move through New York cityscapes, along streets and bridges at night. In other sequences, the camera follows interminable journeys along the seabed. Fire and ash recur as motifs, as well as membranes – as casings for organic substances or as veils in flowing water. They are reminiscent of a life cycle beyond our physical mortality, as well as of the waste we are leaving for other species and generations to take care of.

Korakrit Arunanondchai’s work contrasts the clamour from a complex, globalized world against the stillness of other dimensions, in a practice that carries both the hand’s imprint in tactile materials, as well as sophisticated technical solutions.

Between the narrative works, Arunanondchai embodies a transient, sensory cycle in the rooms with his ghost layer, an immaterial stratum of time-based expressions in a borderland between the dead and the living. An affinity emerges with foregoing generations of artists who have worked with alternative worlds as forms of liminal experiences, such as Pierre Huyghes’s dreamy dystopias, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s urban explorations, or Olafur Eliasson’s phenomenological experiments. Among earlier examples of immersive work with a focus on psychological introspection, vulnerability, and melancholy are those that were created by the American-Tunisian artist Colette. Her “inner sculptures” – multimedia installations and performances – had elements taken from punk, fashion, and street. These are environments that the Canadian artist Miriam Schapiro called “femmages”, a portmanteau of femme and collage. Recurring in Colette’s work was a preoccupation with psychasthenia, which today is a term no longer employed for women’s depression and obsessive behaviour. “Real Dream” (1975), shown at The Clocktower in New York, was an almost baroque tableau vivant with layers of parachute silk and voyeuristic mirrors, to the sound of birdsong, voices, and sound effects. The artist herself appeared naked in the piece, in a public act of seduction similar to Édouard Manet’s “Olympia” (1863). But Colette’s way of exposing herself can rather be understood as a sharply political reflection on women’s position in contemporary public space*.

This mixture of media, ecology, and geography can also be found in Nam June Paik’s work, such as “TV Garden” (1974), in which forty TV screens were placed among tropical plants in what was, at that time, a high-tech collision with nature. The video work “Global Groove” (1973, with John J. Godfrey), which was shown on the screens, was an electronic collage of media images, which mixed Japanese Pepsi advertisements and light entertainment with TV appearances by politicians or cultural figures, such as Richard Nixon, John Cage, and Allen Ginsberg. In Paik’s work, as in Arunanondchai’s, the video material becomes simultaneously a window and a mirror, an observation of the state of things and a personal meditation. In the piece, new visual information is generated through the meeting between the fragmentary, distorted TV images and the uncontroversial nature. There is space for the claim that everything we are aware of exists on the same terms, a sort of harbinger for object-oriented ontology, in which technology is seen as an extension of the human’s sphere. “Nature is beautiful,” Paik said, “not because it changes beautifully, but simply because it changes.” The choice of plants was a personal reference to his birth country, Korea, from which his family fled during the war in 1950, here grafted into the supposedly neutral – albeit defined by the West – white cube.

His way of everting the individual’s relationship to the world around them, and upturning hierarchies between the personal, the esoteric, and the political, questions humans’ conditions in other contexts.

Korakrit Arunanondchai’s work contrasts the clamour from a complex, globalized world against the stillness of other dimensions, in a practice that carries both the hand’s imprint in tactile materials, as well as sophisticated technical solutions. His way of everting the individual’s relationship to the world around them, and upturning hierarchies between the personal, the esoteric, and the political, questions humans’ conditions in other contexts. But the work does not comment explicitly on our relationship to nature and its harvest, as in Italian artist and poet Gianfranco Baruchello’s life’s work “Agricola Cornelia” (1973–1981), nor does it on innovation and industry. Rather, here, a nervous system develops that runs through and between the works, behind the thin skin of textiles. A living organism expands through distributed intelligence and it develops energy, perception, and experience. Paintings expand into sensorial environments, video projections sweep through reflective surfaces of water and bleed out over the walls. A temporal layer of sensory expressions wander through the exhibition rooms and bring rhythm to their breath.

Notes

* Arthur C. Clarke, Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible, New York: Bantam, 1964.

* May Adadol Ingawanij, “Stories of Animistic Cinema,”Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 2, no. 2 (2018): pp. 9–41. After the boys were rescued from the Tham Luang cave, several grand film screenings were arranged as a form of thanks to higher powers, one of which took place in a temple in Bangkok and was projected onto 26 screens at once.

* About the work on the films Tropical Malady (2004) and Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010), “10 Years After – A Conversation between Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Korakrit Arunanondchai and Mark Peranson,” Songs for dying, Songs for living, Milan: Mousse Publishing, 2022, p. 175.

* Today there are around half a million stateless people registered in Thailand, without the right to vote, buy land, carry out certain jobs , or travel freely. The actual, unrecorded number is estimated to be 3.5 million, according to the International Observatory on Statelessness.

* This gesture, introduced by Suzanne Collins in the book The Hunger Games (2008), came to be used by people demonstrating against the military junta’s coup in Thailand that year. It also has occurred in protest movements in other parts of the world.

* The work includes lines borrowed from French poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant (1928–2011), Polish author and Nobel Prize laureate Czesław Miłosz (1911–2004), and French philosopher, mystic, and activist Simone Weil (1909–1943).

* Faye Ran, A History of Installation Art and the Development of New Art Forms, New York: Peter Lang, 2009, pp. 201–202. In 1978, Colette Justine (aka Colette Lumière, 1952–, Tunisia) ultimately took control over her persona after her “death” during a performance at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, as the only heir and CEO of the company Colette is Dead, Co.