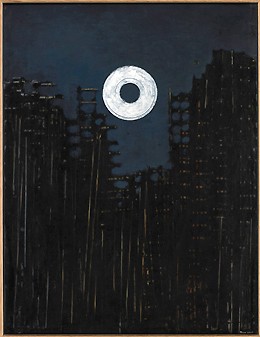

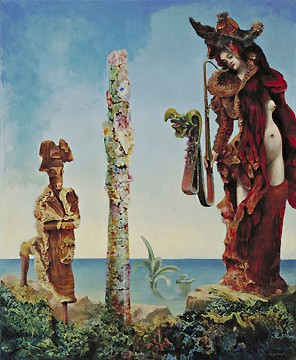

Max Ernst, Den imaginära sommaren, 1927 © Max Ernst/BUS 2008

Collage, Frottage, Grattage…

Collage

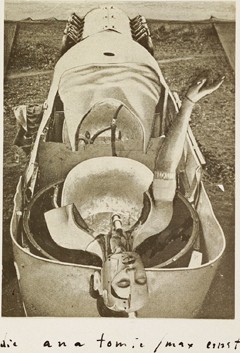

The collage, an artistic technique in which diverse pictorial elements are pasted together on a surface, was characterized by Max Ernst as follows: “The collage technique is the systematic exploitation of the accidentally or artificially provoked encounter of two or more foreign realities on a seemingly incongruous level – and the spark of poetry that leaps across the gap as these two realities are brought together.”

The starting point of the collages made after 1919 were images that did not come from an artistic context, rather, it was illustrative material originally printed in teaching aids, catalogues, and fashion brochures, in addition to charts taken from scientific encyclopedias dealing with the subjects of botany, zoology, and mechanics. Fascinated by this material, Max Ernst reported: “I found figural elements united there that stood so far apart from each other that the absurdity of this accumulation caused a sudden intensification of my visionary facilities and brought about a hallucinating succession of contradictory images.”

In his collages, the joints between the individual illustrations were pasted in such a way that the transitions are invisible, hence producing the illusion that the image has its pictorial reality. This impression was often further underscored by means of the photographic enlargement and reproduction of the collages, as can be seen in works such as C’est déja la 22ème fois que Lohengrin… (It’s already the 22nd time that Lohengrin…) from 1920 or Sambesiland (Zambeziland) from 1921, for example. With this pictorial illusion as a goal, Max Ernst’s works differ from the Cubist papier collés produced by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, which were concerned instead with the reintroduction of an outer reality into art’s pictorial world.

Frottage

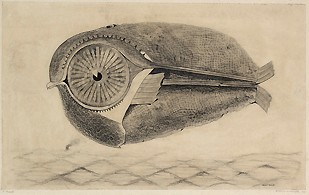

Max Ernst started using the frottage technique in his work in 1925. As some might still recall from their childhood days, this technique involves laying a piece of paper on a structured surface and making a rubbing of its texture with a pencil.

By his own admission, Max Ernst discovered this technique for himself on the rainy afternoon of August 10, 1925, when he observed a washed-out wooden floor in a hotel at Pornic on the French Atlantic coast. The floor’s structure inspired him to place a piece of paper on the floorboards and then transfer its textures to the sheet with graphite.

Aside from wood boards, he also utilized textures from leaves, bark, thread, straw, textiles, netting, and dried paint as the starting point of his frottages. He regularly shifted the paper while rubbing: “When I intensely stared at the drawing won in this manner, at the ‘dark spots, and others of a delicate, light, semi-darkness,’ I was by the sudden augmentation of my visionary facilities with contrasting and superimposed pictures.”

Inspired by the resulting structures, associations were produced that the artist reshaped into new pictorial worlds. In 1925 he put together a selection of frottages for the portfolio Histoire naturelle. The thirty-four prints in the series were reproduced here as lithographs in order to further underscore the impression of their pictorial reality compared to the original frottages.

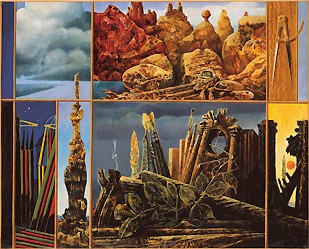

Grattage

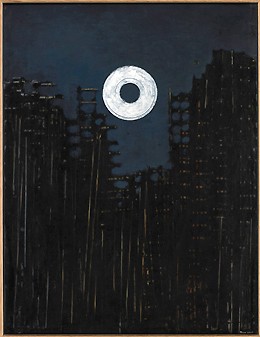

In 1927, Max Ernst developed the grattage as an application of the frottage technique in painting. Richly textured, relief-like materials such as wood, wire mesh, pieces of broken glass, and cord were placed under a canvas primed with numerous layers of paint. The individual layers of paint were scraped from the canvas pressed onto the textured object using a palette knife or spatula.

The textures pressed themselves through the still-wet paint with the result that the characteristic features of the underlying objects were lost. Subsequent reworking with paintbrushes caused a further transformation of the structures achieved in this manner. They could become forests, water cabbages, birds, sun crosses, and petrified cities.

In his essay “What is Surrealism?” (1934), Max Ernst said of such transformations: “The joy in every successful metamorphosis conforms . . . with the intellect’s age-old energetic need to liberate itself from the deceptive and boring paradise of fixed memories and to investigate a new, incomparably expansive areas of experience, in which the boundaries between the so-called inner world and the outer world become increasingly blurred and will probably one day disappear entirely.”

Inner and outer world, the subconscious, fantasy and reality are linked together in Max Ernst’s pictorial worlds. This is a characteristic feature of his entire oeuvre.

Decalcomania

The transfer technique already developed in eighteenth-century England known as decalcomania was first used by the Surrealist Oscar Domínguez in 1936 and later taken up by Max Ernst. The artist produced works starting in the late 1930s in which paint was spread over some parts of the canvas, then glass or a sheet of paper was pressed onto it.

Chance air bubbles, rivulets, and branchings of paint producing a varied surface structure also came about when the glass or paper was lifted from the canvas. In a further step, he used a paintbrush to transform the found structures, recalling coral or moss.

Leonardo da Vinci had already discussed a similar artistic procedure around 1500 in his Trattato della pittura: “when you look at a wall spotted with stains, or with a mixture of stones, if you have to devise some scene, you may discover a resemblance to various landscapes, beautified with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, plains, wide valleys and hills in varied arrangement.”

Stimulated by the structures, it became possible to produce stalagmite-like thickets populated by fantastic creatures on the canvas. By adding paths and horizon lines, the artist was able to create the impression of fantastic landscapes in works such as Napoleon in the Wilderness from 1941, Arbre solitaire et arbres conjugaux (Solitary tree and conjugal trees) from 1940, or The Stolen Mirror from 1941.

Oscillation

Max Ernst began working with the oscillation technique in 1942 while in exile in the United States. He explained that the technique is a cakewalk: “Attach a one or two meter long cord to an empty tin can, drill a small hole in the bottom, and fill the can with liquid paint. Swing the can at the end of the cord back and forth over a canvas lying flat, guide the can with movements of the hands, arms, shoulders, and the whole body. Drip surprising lines onto the canvas in this manner. The game of combinations can then begin.”

The technique that foregoes control to a large extent, results in compositions comprising circles, lines, and dots whose networked structures in such works as L´année 1939 (The Year 1939) from 1943 or Jeune homme intrigué par le vol d´une mouche non-euclidienne (Young man intrigued by the flight of a non-Euclidean fly) from 1942 to 1947 recall the orbits of the planets around the sun. However, Max Ernst also made use of the oscillation technique just as a starting point, enabling him to transform the structures he achieved in this manner into new pictorial worlds.