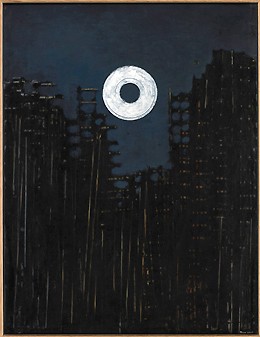

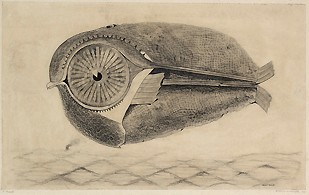

Max Ernst, Painting for Young People, 1943 © Max Ernst/BUS 2008. Collection Ulla & Heiner Pietzsch, Berlin. Photo: Jochen Litkemann

Sparks of poetry

Interview from Bulletinen (The Bulletin), No 5, 2008, The Friends of Moderna Museet

John Peter Nilsson: Max Ernst lived in 1891-1976. Who was he?

Iris Müller-Westermann: Max Ernst was a multi-faceted, intellectual artist personality. He studied philosophy, psychology, psychiatry and art history, and was profoundly interested in literature. He never studied at an art academy, however, and was a self-taught artist. Perhaps it is this very lack of artistic training that made it possible for him to think in radical new ways.

Ernst was a restless soul, a searcher throughout life. He was not interested in producing an easily recognisable oeuvre or style. On the contrary, he looked for resistance and challenges by changing style and approach repeatedly. He rebelled against the norms and opinions that characterised his parent generation, a generation that had started the First World War and all the suffering it involved. After that, art could not continue as before.

JPN: How is he linked to surrealism?

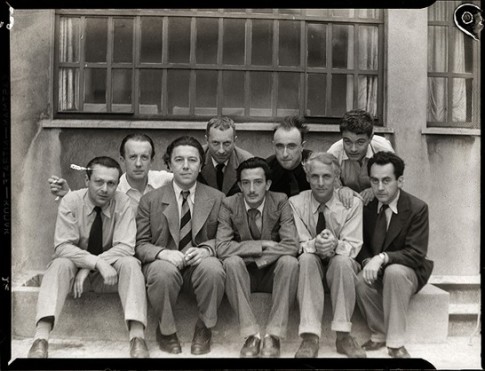

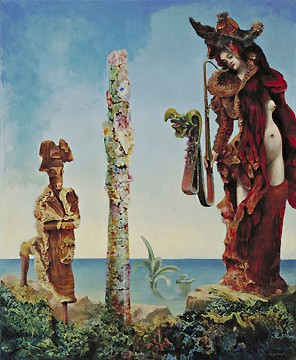

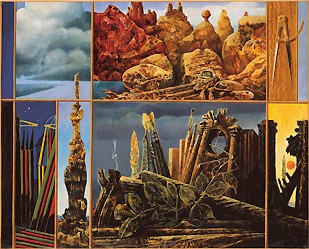

IM-W: Back in 1920, Max Ernst’s collages inspired André Breton, Paul Eluard and the circle of intellectuals in Paris who later called themselves the surrealists. (The “Surrealist Manifesto” was published by Breton in 1924.) In these collages he combined foreign worlds, intending that the encounter between these worlds would generate sparks of poetry. Eventually, he transferred the collage technique to paintings, for instance in “Celebes” (1921) and “Oedipus Rex” (1922), which he made while still living in Cologne. Surrealism was originally a literary movement, but Ernst gave it a visual counterpart. Although he mixed with the surrealists when he moved to Paris, as a person he was always wary of belonging to a group.

JPN: Is it hard to distinguish between Ernst’s private life and his art? After all, surrealism is often about private dreams, taboos…

IM-W: As with most artists of the first water, it is hard to separate art from life, including private life. That is true of Max Ernst too. He was an artist who always chose unconventional women with strong personalities. His first wife, Louise Strauss-Ernst, was exceedingly intellectual, and Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning (his last wife), were artists. But his works nevertheless reflect life in general rather than private matters. He wanted to visualise the great, universal issues.

The subtitle of the exhibition refers to the surrealists’ fascination for the dream state as a way of reaching the unconscious, and this is the key to the surrealist questioning of ideas and notions that their parents’ generation had nurtured with narrow-mindedness and bigotry. This approach holds a revolutionary dimension, an opposition against existing restrictions and an assertion of greater freedom.

JPN: Max Ernst is also famous for his experiments with new techniques. What drove him to explore and invent new artistic methods?

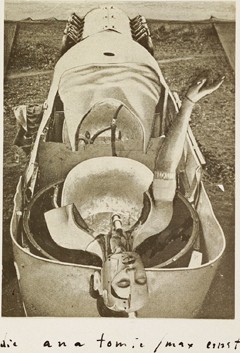

IM-W: It is characteristic of Max Ernst that he did not make art out of other art but from materials that he found outside the artistic idiom. His collages could originate in educational wall charts or illustrations from popular fiction, which he combined to create something new. After the “Surrealist Manifesto” was published, he began experimenting with methods that he used to access sources in his own unconscious. With the “frottage” technique he rubbed a pencil over a sheet of paper spread over wood, for instance, to transfer the various textures. Later on, he developed “grattage”, which is an adaptation of the “frottage” to oil painting, and the “décalomanie” technique, which involves laying, for instance, a sheet of glass on partly wet oil paint and then elaborating on the result once it has dried. During his exile in the USA, he also created the “oscillation” technique, where he splashed paint on the canvas straight from the cans. With these semi-automatic methods, he wanted to open the door to his unconscious. The techniques generate the starting point for pictures from imagination. To use a modern term, his works of art can be seen as an “interface” between fact and fiction – between an external and internal reality. Part of this is that he also refuted the idea of the artist as a genius touched by divine inspiration. Max Ernst was inspired by things beyond the exalted world of art.

JPN: How would you say that Max Ernst’s imagery is relevant today?

IM-W: The collage as such is very contemporary. With the act of selecting and combining, Ernst challenged existing norms, an approach that is familiar to us nowadays. Max Ernst reacted to a fragmented world, something that many artists today will recognise. And a lot of contemporary art has a similarly dreamlike, surrealistic, imagery. These are pictures aimed to create domains of freedom in an increasingly puzzling world, while exploring an extended vision and the potential for greater freedom, pictures that formulate a critique of the existing world. Max Ernst’s imaginary worlds are echoed by the imaginary worlds that we find in computer games and so-called fantasy literature.