Cindy Sherman, Untitled. From the series Fairy Tales, 1985 Photo: Åsa Lundén/Moderna Museet Bildupphovsrätt 2023

Art and Capital

in the Transgressive 1980s

As the 1980s came to an end Sweden left behind a decade of both ambition and unease. The World Wide Web had just been launched, the Berlin Wall had fallen and an over-heated financial market would soon crash. In many ways the 1980s was the decade when the outside world came to Sweden. The country found itself squeezed between the grumbling military blocs of the Warsaw Pact and NATO. In 1982 the first Swedish case of HIV was discovered in a patient at Roslagstull Hospital, and the virus caused a great deal of fear in society. Another invisible threat that characterised the mood of the time was nuclear energy. The 1990 financial crisis in Sweden was a dramatic conclusion to the stock market boom of the late 1980s. Sweden went from being the world’s most equal nation at the beginning of the decade to being a country with a deregulated financial market and growing economic disparities.

The 1980s was also a period of upheaval in art. The way artistic mediums and materials were used was radically transformed, and hierarchies of genre and style were turned upside down. The art scene in Sweden began to open up internationally and played a part in the boom that had developed in the art market. The financier and art collector Fredrik Roos built one of the most highly valued private collections of contemporary art in Sweden at that time, and he made a great impact on the commercial art scene. In parallel to this an alternative, underground scene emerged. Philosophy and theoretical discourse became commonplace in art contexts, and a more intellectual role for the artist began to appear.

Postmodernism

The increasing visual flow from mass media and popular culture, on the rise since the 1960s, resulted in more and more artists becoming interested in what lies behind an image. The shrinking lifespan of an image and the way images come about and subsequently shape our perception of reality became key subjects. The construction of the self and of gender roles were examined and deconstructed. This desire to reveal underlying structures was also directed at art itself, something that was expressed in, for example, intricate, playful titles and an interest in the conditions of art. All these tendencies are associated with postmodernism.

A basic definition of postmodernism is that it denotes a period that replaced modernism and its coherent notion of progress. In the USA pop art and conceptual art had already begun a reckoning with the formalism that modernist art had come to represent. This was something that the art critic Leo Steinberg had observed at the end of the 1960s, and he was an early adopter of the term in the context of art. If the artists of modernism – and particularly of late modernism – were intent on finding a medium’s true expression, artists were now turning away from ideas of truth and essence. The creative subject, which during modernism had been at the heart of artistic explorations, had to take a step back in place of a more fragmentary approach without any given benchmarks. A traditional view of art focussing on painting and sculpture was now replaced by a wider understanding; new hybrid forms and mediums, such as installation art, took hold. The way the role of the artist was thought about was also disrupted, and the importance of the viewer and the conditions of the creation of meaning were asserted. Concepts such as ‘gap’, ‘appropriation’ and ‘context’ became recurrent terms in art vocabulary.

With the influential text “The Postmodern Condition” (1979) philosopher Jean-Francois Lyotard captured the zeitgeist, describing how the era of ‘grand narratives’ had come to an end. The debate surrounding postmodernism reached its highpoint in New York by the mid-1980s. In this context Fredric Jameson’s marxist analysis “Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism” (1984) emphasised postmodern cultural expression as a natural result of the impact of a late capitalist system on people’s lives.

Neo-expressionism and the Pictures Generation

Within painting postmodern theories gave rise to questions about the viability of the medium itself: Was it possible to revive painting or had it had its final act? In Germany Expressionism had a revival during the early 1980s with the artists dubbed Die Neuen Wilden (The New Wild Ones), or Neo-Expressionists. In Italy a similar movement took place under the name Transvanguardia. References and signs from popular culture and art history were freely mixed on large canvases. The Neo-Expressionist style of painting reached its international peak in New York galleries and auction houses during the second half of the 1980s, with the artist Julian Schnabel as its poster boy.

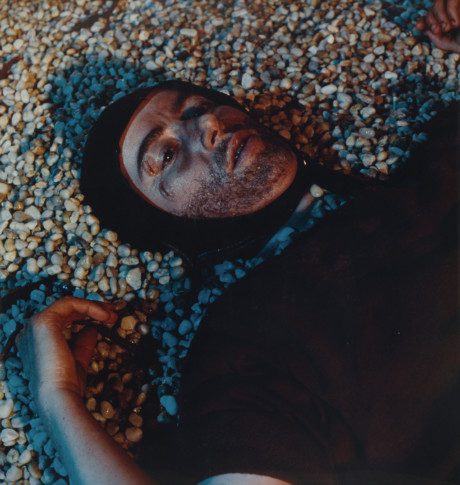

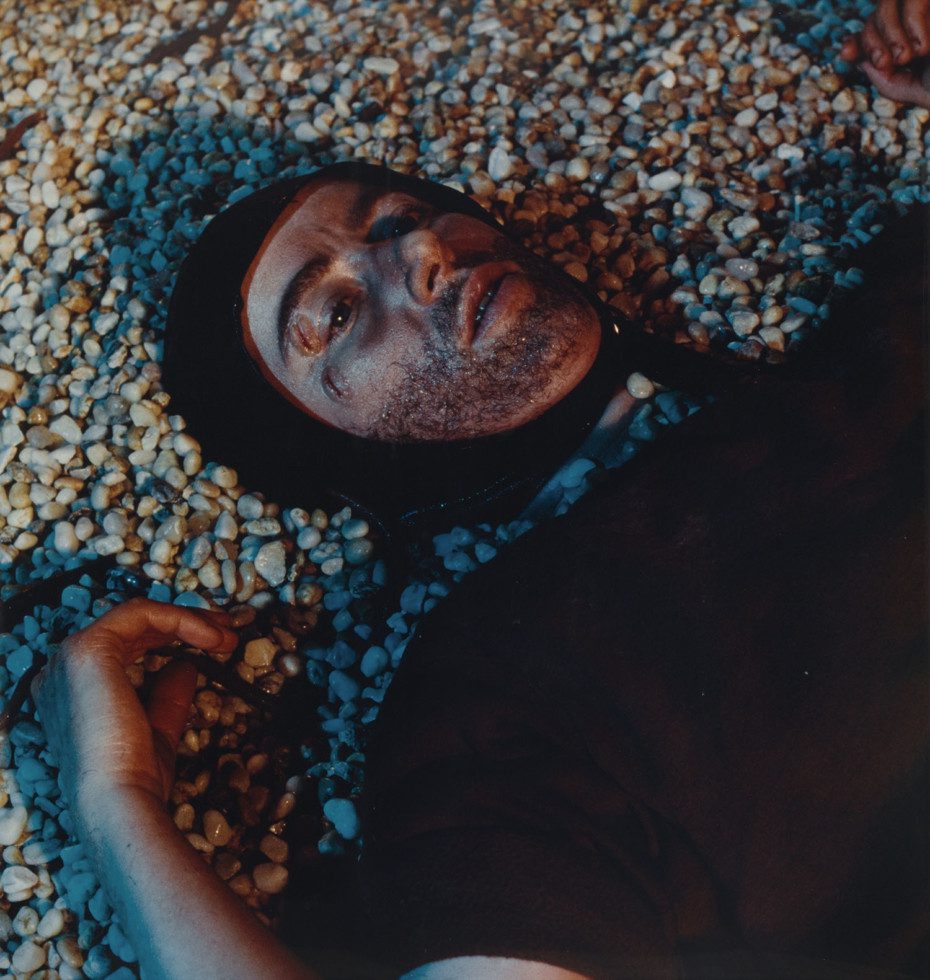

Many female artists chose to turn away from painting in order to try mediums which were perceived as less anchored to the male cult of the genius. In 1977 the exhibition Pictures opened at the gallery Artist Space in New York. The show became the starting point for the influential ‘Pictures Generation’, a loosely connected group including, amongst others, Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, Barbara Kruger and Richard Prince. Several of the artists’ work was cross-disciplinary, but the group was predominantly associated with photography and video. What they all shared was a view of the image as a palimpsest; layers of representations and meaning, the origins of which are impossible to retrace. They worked with images sourced from mass media, advertising, popular culture and art history in order to reveal the constructions behind contemporary pictures of reality.

In Sweden Teresa Wennberg was a pioneer within video art and computer art. She spent long periods in Paris where there was a greater acceptance of these new artistic mediums. Ingrid Orfali’s Surrealist photographs captured a female, corporeal experience, whilst being loaded with political and philosophical references. With a double Ph.D. in semiotics and French, Orfali was well acquainted with the postmodern discourse of the time.

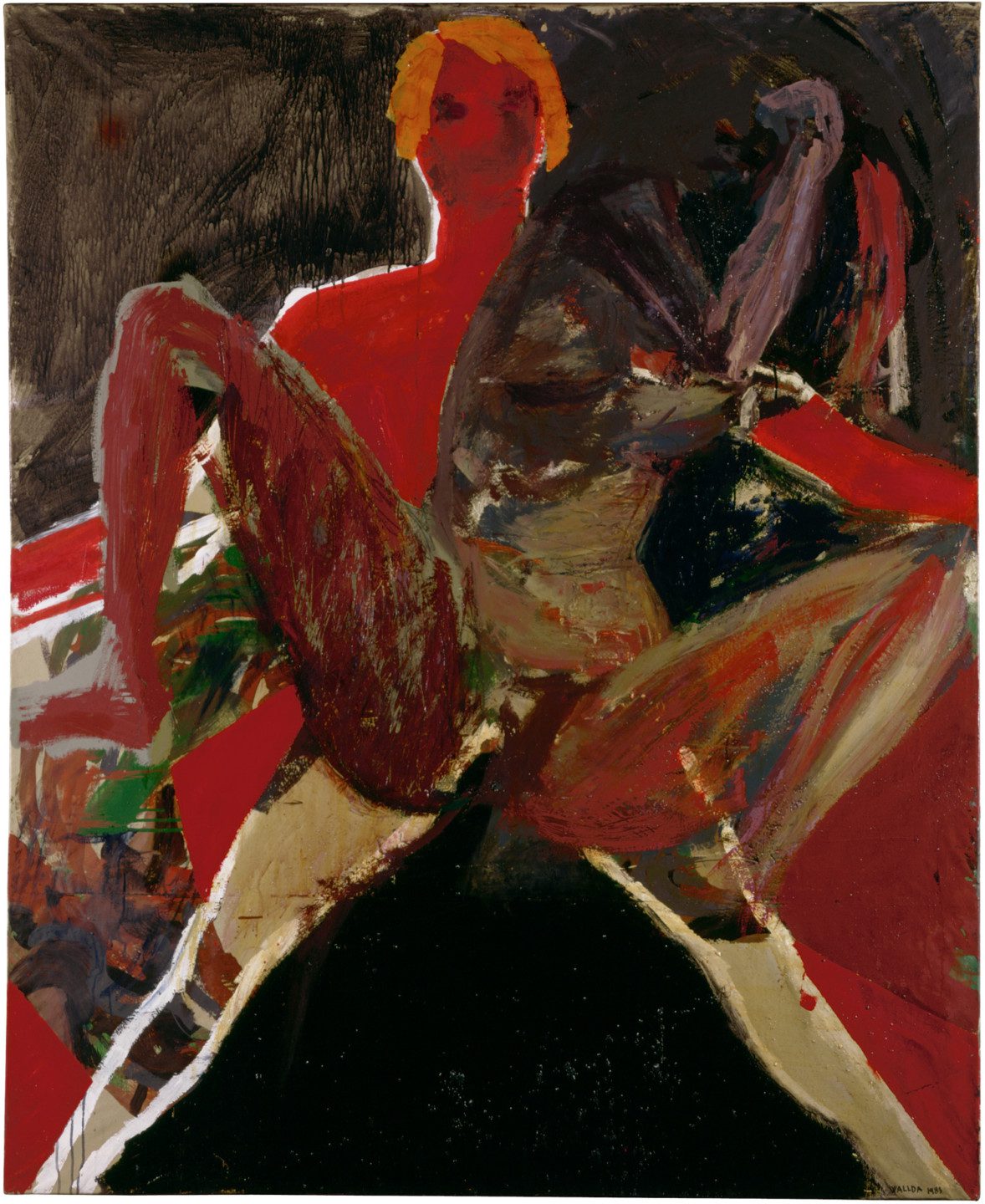

The Wallda Group

The Swedish art scene underwent a radical transformation during the beginning of the 1980s. The cultural sphere in the country had for some time been relatively isolated, and everything connected to the USA had been considered despicable. Now a new generation had arrived, one who looked beyond the borders of Sweden and who wanted to break with the dominant political narrative of the time. Although the art of the 1980s was no less critical of contemporary society than the art of the 1970s had been, the role of the artist changed. A more pleasurable, wild, but also austerely intellectual art emerged. Many artists moved more freely across both ‘high’ and ‘low’ genres and materials. At the centre of this artistic rejuvenation was the Wallda Group, and its members Max Book, Eva Löfdahl and Stig Sjölund. During trips to New York and Berlin they had been inspired by both performance art and the ‘wild’ painting. Now they wanted to create something which didn’t yet exist in Sweden. Together they experimented with performance, cabaret, painting and installations as they, in a number of self-organised exhibitions, diverted from the traditional exhibition space.

In August 1980 Boplats Otto opened at Årstafältet in Stockholm, a large area of mostly green spaces. The name of the show was a pun on the architectural exhibition Boplats 80, going on at Kungsträdgården, in the city centre, at the same time, and which examined new forms of housing and urban planning. In a similar fashion the Wallda Group had also taken their name from the health food shop that had been the previous occupant of their studio space in Årsta. The quiet area of Årstafältet was a space located in between city and suburb – a kind of no-mans land where anything could happen. Eva Löfdahl showed a series of outdoor toilet-like huts that merged abstract painting, sculpture and installation.

Boplats Otto became the first of several exhibitions shown in unconventional places in Stockholm, like, for example, industrial spaces or in the closed-down Seraphim Hospital on Kungsholmen. The Wallda Group also participated in exhibitions at museums and art institutions around the country, often with their ‘collective paintings’. At the same time the studio in Årsta became a place where, in the spirit of Fluxus, they engaged in cabaret activities. After a few intense years of collaboration the group dispersed and the artists continued to work individually. Max Book became influential during the 1980s with his large, humorous and mysterious paintings, whose poetic titles trod the line between sense and the absurd.

Fredrik Roos

One visitor to the Årsta cabarets was the art collector-to-be Fredrik Roos. During the next ten years his collection would establish itself as one of the most significant in Swedish art history. By 1980 it was still very unusual to sell your work on the commercial art market as a newly graduated artist. When Roos purchased a number of works by the young Wallda artists this was a sign of the changing times.

Fredrik Roos’ development as an art collector happened in parallel with his skyrocketing career as a financier. Age twenty-three, and after an unsuccessful investment, he began working as a broker, entering a still rather dormant Stockholm stock exchange. The oil crisis of 1973 had caused a long term international depression. At the same time the financial market had gradually become more international thanks to new technology that allowed faster and larger transactions to take place. This, in combination with the introduction in many countries of flexible exchange rates, contributed to a new financial policy taking shape in the West. With Margaret Thatcher’s ‘Thatcherism’ and Ronald Reagan’s ‘Reaganomics’ the Western world’s economic playing field was radically redrawn. Regulations on the financial market were softened and a global market economy was set in motion. Sweden resisted these measures for a long while, but in the mid-1980s regulations began to be dismantled here too. In May 1985 interest rate regulations were abolished, and in November the loan cap was too. The reform – the so-called November Revolution – meant that banks could now lend unlimited sums of money. With lucrative tax conditions it also became highly advantageous to borrow. Sweden was quickly drawn into the financial boom that gave rise to concepts such as ‘sharks’ and ‘yuppies’.

The risk-taking and fast pace of the stock exchange suited Fredrik Roos. He became obsessed by the financial market, and with new technology, which he was almost the only one to use in Stockholm, he was often one step ahead of his competitors. He brought this understanding of a good investment with him to the art world, which at this time was gaining in social prestige. Roos distinguished himself as a curious and motivated art collector, always diligent in seeing the artworks with his own eyes and keen to be in dialogue with the artists. He continued to acquire art by young Swedish artists. Apart from the artists of the Wallda Group, whom he followed for several years, he bought pieces by, amongst others, Ingrid Orfali, Ola Billgren and Cecilia Edefalk. Roos also spent a lot of time in New York galleries. At one point he owned twenty-one paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat and, like many art collectors of that period, he was particularly interested in Neo-Expressionist painting. Roos was also early in buying works by several of the artists from the Pictures Generation.

With the foundation in 1988 of Rooseum in Malmö Roos realised his vision of giving his art collection a worthy exhibition space. Private art institutions were a new, very of the moment, phenomenon internationally, but no one had yet opened such an institution in Sweden. The first director of Rooseum was the curator Lars Nittve, who during a few intense years presided over a significant program of exhibitions. Today many of the works are included in Moderna Museet’s collection.

The AIDS crisis

When Fredrik Roos passed away from the effects of AIDS at his home in Stockholm in 1991, the fear and ignorance surrounding HIV was still rife. In 1982 the first person in Sweden had been diagnosed with AIDS, but it would be a few more years until the disease was given attention in the media. To begin with doctors knew very little about the effects of the virus and how it spread, but fairly quickly it became clear that homosexual men were one group that was particularly affected. The fight for LGBTQ rights had seen some progress during the 1970s, but the AIDS crisis represented an enormous step backwards.

As fear took hold on society homophobia increased. The double stigma made many people choose not to tell about their illness. It wasn’t until 1987 when fashion designer Sighsten Herrgård became the first person in Sweden to open up and speak publicly about his illness. He got a massive response. Many celebrities openly showed their support and the fight against the disease entered a new phase. In art and culture the illness was a constant sombre presence due to the many artists and cultural personalities that passed away from it. The New York art scene was badly hit and many artists became engaged in what was considered the un-democratic handling of the crisis. Keith Haring, David Wojnarowizc and Robert Mapplethorpe were only a few of the artists who lost their lives to the disease.

Implosion – a Postmodern Perspective

The year before Lars Nittve assumed his role as director of Rooseum he had curated the much noticed exhibition Implosion – a Postmodern Perspective (1987) at Moderna Museet. Through the show Nittve introduced to a Swedish audience a selection of works from a contemporary – predominantly American – art scene, whilst at the same time connecting it with elements of early European modernism. During his studies in New York in the beginning of the 1980s Nittve had had many exchanges with the artists he now included. Other, older works in the show, by Robert Rauchenberg, Andy Warhol and Donald Judd for example, were already part of the museum’s collection. At this time the perspective on Marcel Duchamp had been radicalised amongst artists in New York. His ‘ready-mades’, which had undermined the artistic subject’s role in the creative process, were increasingly highlighted as a prelude to postmodern art. Moderna Museet’s historic collection of works by Duchamp therefore became a natural beginning for Implosion. Points of connections that ran from Duchamp and Francis Picabia via pop art, minimalism and conceptual art emerged in the exhibition.

The younger generation of artists in the show belonged to the Pictures Generation and had, by this stage, taken issues regarding representation, authenticity and identity construction to a head. Almost all were women, working with photography and video from a feminist perspective: Cindy Sherman, Dara Birnbaum, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, Sherrie Levine, Laurie Simmons and Gretchen Bender. Louise Lawler did one of her ‘arrangements’, where on a defined area of grey-painted wall she hung two pieces from the museum’s collection, one by Roy Lichtenstein and one by Andy Warhol, next to four of her own photographs. One red, one blue, one green, and one yellow. The photographs, identical apart from their colour, represented the shadows of Marcel Duchamp’s work Air De Paris (1919); a small glass ampoule containing Parisian air, which had earlier on been installed at Moderna Museet amidst a complex web of strings, tied according to the principle of the Golden Ratio.

A deliberate point of consideration in Implosion was the dislocations and contradictions that appeared between the works. It wasn’t a unified, chronological history that was presented, but rather a group of works whose mutual relationships could be interpreted in various ways. The show got a large response both in Sweden and internationally and became one of Moderna Museet’s most important exhibitions. Many of the artists shown were new to a Swedish audience. But, perhaps the biggest impact that some of these artists made was on a generation of young female artists working with photography and video, and who, during the 1990s, would come to have a strong presence on the Swedish art scene.

Text: Sanna Marander, artist and writer