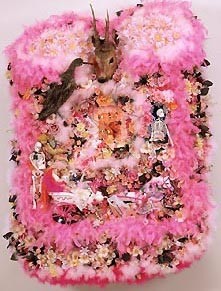

Anna-Maria Ekstrand, Box © Anna-Maria Ekstrand

Passing (Sprawl 3)

Chevalier d’Éon worked hard to compromise the ambassador, but when the Seven-Year War broke out he was transferred to the army. He played a key role in the Battle of Prague in 1757, which Frederick the Great called the bloodiest battle of all ages. At the peace talks in London in 1762, d’Éon was commissioned to secretly make contact with the Tories. After furtive bargaining, he managed to achieve a peace treaty. D’Éon was awarded the St. Louis Cross for courage in battle and was given a post as first secretary at the French embassy. But the ambassador, Comte de Guercy, never fully accepted the appointment and Chevalier d’Éon eventually felt forced to resign. Before leaving, however, he managed to get his hands on a number of compromising documents that revealed bribery in connection with the peace negotiations, as well as French plans to invade Britain. The next few years were hectic for d’Éon. The parliamentary members tried to buy back the documents for 40,000 pounds (an enormous sum in those days). Guercy sent agents to steal the documents, and even to kidnap him, but to no avail. Instead, d’Éon established himself as a wealthy gentleman in London society. He was even elected into the Masonic Lodge of Mortality, which had its temple at the Crown and Anchor on the Strand. In 1764, however, a rumour started that Chevalier d’Éon was a woman. By 1769, the rumour had won such credibility that people started placing bets on the sex of d’Éon. But betting was against the law in Britain in the late-1700s, so an insurance company was formed for the purpose, Policies of Insuerance on the Sex of Monsieur Chevalier (or Mademoiselle la Chevalière) D’Eon. The wagers soon amounted to £120,000. Betting continued until 1777, when punters finally lost interest and sued the “insurance company”. The matter could easily have been resolved with a medical examination, but d’Éon refused to cooperate, despite the offer of £25,000. The court verdict had to be based on testimonies. What spoke in favour of his being a man was that he was a decorated officer of the French army, and, above all, a Freemason. At the initiation rite the novice has to appear before the Lodge bare-chested, and women were absolutely prohibited from membership. The fact that he had never been seen to court women inferred that he was a woman. The judge, Lord Mansfield, let the matter be settled by two French witnesses, a journalist and a doctor, who swore under oath that d’Éon was really a woman.

This testimony set the wheels in motion. The French government recalled all Chevalier d’Éon’s privileges, his uniform and his medals, and struck him off the embassy’s payroll. Moreover, a royal decree from 19 August 1777 forbade him from ever wearing men’s attire. But d’Éon had already started dressing in women’s clothes before the decree was issued. He retired to the family seat in Burgundy and joined an order of nuns. In 1785, he applied to King Louis XVI for permission to travel to London to pay his debts, and having obtained permission he stayed there until his death on 25 May, 1810. He lived the last 25 years of his life in extreme poverty and always wore women’s clothes.

After his death, Chevalier d’Éon was examined by the famous French surgeon Père Elisée and his colleagues, who were shocked to find that Mademoiselle d’Éon was, after all, a man. To remove any vestige of doubt, they summoned the Earl of Yarborough and Admiral Sir Sidney Smith, who were also Freemasons, and another twenty witnesses, who all certified the sexual identity of Mademoiselle Chevalière/Monsieur Chevalier d’Éon.

Of all the romantic ideas Walter Benjamin passed on to us, his The Arcades Project (Das Passagenwerk, 1983) is perhaps the one that has had the greatest impact. Benjamin studied 19th century Paris and the dawn of modernism from the perspective of the commercial streets that were covered following the development of steel and glass building methods, and the “rites of passage” that have been a central object of study throughout the short history of anthropology. Anyone who has read The Arcades Project will agree how packed it is with observation. The arcade leads to awakening leads to revolution leads to psychoanalysis leads to conspiracy. Perhaps we should refrain from scrutinising it, but Benjamin mistakenly relates the shopping arcade to the rite of passage. This rite is a very distinct transition from one state to another. From childhood to adulthood, from peace to war. The power and mythological charge of this threshold, this triumphal arch, derives from the tension between the different states. Roman mythology, for instance, is full of threshold myths, the most well-known perhaps being the bride who is carried over the threshold after marriage. (Roman mythology was gender-neutral, however, and both the bride and groom could be carried over, either one or the other separately or both together.) The shopping arcade, or passage, was not a rite of passage, but simply a shelter against the weather. And we can toy with the thought of where we might have ended up if Benjamin had instead written about the other major 19th century capital, London, and The Mall.

In 1929, Nella Larsen published her book Passing, which immediately became a cornerstone of the Harlem Renaissance, a circle of novelists, poets and artists on North Manhattan, who suddenly advanced the position of black Americans, to the soundtrack of Duke Ellington. In the book, Clare Kendry gains entry to the white middle class by renouncing her Afro-American heritage. What is fascinating today is that she not only manages to change her culture and ethnicity, but also her skin, her race. Remarkably, this change is both literal and figurative. She has unusually pale skin for a black person, so she is passable in her new environment. Racial passage, for and against, is a central theme, especially, perhaps, in American culture and literature. Sexual passage is less common, but history abounds with stories like that of Chevalier d’Éon. It was more common, naturally, with women who were forced to pretend to be men, in order to pursue their goals, like Victoria Benedictsson – Ernst Ahlgren. But the most common form of passage is from one social class to another, to escape class oppression. There are few instances in history of the lower class rising not only to change class, but to claim the right to have their own taste. Strangely, Walter Benjamin does not mention either Nella Larsen’s book Passing or the Harlem Renaissance, even though it is an extraordinary example of a threshold that is transformed into an extensive protection against the climate.

But more often, not to say usually, or nearly always, we keep at a safe distance, outside the bars, the wall, the shop window, or below the stage, when regarding the unfamiliar. Side-shows, they were called, the circus tents with freaks. The name comes from their position slightly offside at the big world fairs. Audiences could gape at strange aberrations of nature: dwarves and giants, bearded ladies and women without a lower body, dog boys and cat girls, Siamese twins, snake women, hermaphrodites and living skeletons. Here was a threshold that we had definitely been spared from crossing. Yes, there is still a side-show today, on the outskirts of the fairground on Coney Island. Freaks put our normative tolerance to the test, but the test is to be non-passing. The boundary is clear. This is a threshold you should not cross. Only the forlorn pass through that triumphal arch. Freaks have always been subjected to close scrutiny. Science has long devoted its time to peculiarities, the study of normal phenomena is more uncommon. Long ago, in Mesopotamia (2800 B.C.) freaks were a literary theme. Then came the French categories of monstre par défaut, monsters with missing parts, monstre par excès, monsters with excess parts, monstre double, monsters with duplicate parts, making it possible to classify them: if they only had one eye or were too short, if they had too many legs or too much hair, if they had two sexual organs or consisted of two bodies stuck together. Non-passing.

Mistake or not, it is not surprising that Benjamin could relate the rite of passage to an elongated room. It is not so much the unfamiliar, the strange things we see on the other side, that frighten us. We can feel pity for it. Tolerate it. But when the boundary gets fuzzy, when those who lack or have too much start to glide away from the positions we fixed them in, they become a threat. When passing becomes visible we no longer want to see. The norm, the normal, the neutral, is not what is boring. The norm has different names in different countries but is always that which is of high class, tasteful, artistic. The Greeks called it the golden section, in Sweden we call it ‘lagom’, just right. Fanny Ambjörnsson’s book I en klass för sig (In a Class of their Own), is a wonderful description of the quest for normality (and the failure) among girls in two upper secondary school classes. The girls in the high-status academic line are constantly dissatisfied with themselves and their bodies, working incessantly on the endless project of not slipping down among the freaks. While the freaks (in this case, the girls attending the childcare programme) know they will always provide the wrong answer to the demands and questions and are doomed to have questionable taste. For there are not two ends to the scale. There is a central point, which is the ultimately desirable norm, the good, the cool, and outside the sharp boundary there are oceans of embarrassing hair, ugly or vulgar clothes, unsuitable boyfriends, intolerance and foul language.

A book like I en klass för sig, or Passing for that matter, beautifully decribes the Deleuzeian concept of deterritorialisation. But it also demonstrates how far we are from achieving it (otherwise we would not be here in this setting, an exhibition titled “Swedish Hearts”, at Moderna Museet, in the heart of Stockholm). We rarely tolerate the rhizome other than as an occasional decoration. We struggle feverishly to stay on the right side of the threshold, anything else would be tantamount to giving up, running away. It would be cowardly not to search for what David Harvey calls the spatial fix (The Condition of Postmodernity, 1990). Rarely is this as pronounced as when we talk about class. Especially when we consider that class is probably determined by codes of taste rather than by income. Unlike the Afro-American struggle for social justice for Afro-Americans, or women’s fight for their rights as women in society, with the ultimate goal of dissolving all thresholds into cascades of grey tones, the only permissible way to express class is by passing to another class. The possibility of changing class. Switching to good and safe taste. Honing down one’s dialect and intolerance. Not having to stand there on the other side of the glass and be categorised and gaped at, like all of us have experienced who have lived in the suburbs, in the sprawl: by the voyeurs, the discoverers, the big city adventurers, the taste missionaries, the artists.

Text from the catalogue by: Lars Mikael Raattamaa