Dimitrios Kiriazidis, Untitled, 1998– © Dimitrios Kiriazidis

C-print

Pågående fotoserie.

Folk costume or straitjacket?

For the spiritualist, who worked in a school, this meant she had to tell her colleagues about her activities. She described how hard that was, and compared it to how it must be for a gay person to “come out of the closet”. The episode demonstrates how narrow the margins are for what is considered normal in everyday life. Social pressures and fear of the consequences mean that many interesting phenomena remain invisible. But we also avoid talking about certain experiences out of a wish to belong. Similarly, curators, artists and critics highlight certain segments of the art scene, while playing down others. Representational Swedishness is an edited product, the result of a series of everyday selections. And these selections are ultimately crucial to the individual artist. The Swedish Hearts exhibition examines the Swedish art scene and asks what a work of art can say about what remains hidden in the closet.

A phenomenon in popular culture such as the Eurovision Song Contest is a good indicator of the changes that have occurred over the past decades. Nowadays, The Swedish selection contest for this traditional competition between different nations’ romantic songs can be won by a group such as Afro-dite (a pun alluding both to the beauty of the artistes and to their light-brown skin) in tough competition with the salsa-hip hop genre. Entries can now be in English, and the acts provoked TV presenter Siwert Öholm to launch a diatribe against how this popular event had been transformed into a gay gala. In the field of sports, Zlatan Ibrahimovic is one of Sweden’s most promising new comets. But the love of a nation is fickle. Ludmila Engqvist was our celebrated Swedish hurdles champion, until it turned out she had been doped. The media then dubbed her a dodgy Russian.

In the mid-1980s, Benedict Anderson described the nation state as a perceived, imaginary, community. With the emergence of umpteen new nations since the fall of the Berlin wall and the Soviet Union, it stands out even more clearly that the concept is a construct. National identity is not necessarily based on consensus. People’s ideas of co-existence and the feeling of community seem to find other outlets, such as religions and lifestyles that sometimes both outdate and defy the national boundaries. “Swedishness” does not overshadow everything, and the nation is inadequate as a metaphor for a set of basic shared values.

So how has the Swedish national identity been influenced over the past decades? Can we even talk of nationality as origin (the word comes from the Latin natus, born) – shouldn’t “Swedishness” rather describe the aggregate experience encompassed by the national boundaries, and even stretch beyond the boundaries, to those with memories and experiences from the country? Having remained unchallenged, Sweden has not felt the need to manifest its nationality in the way Norwegians do with their 17th May celebrations. But that does not mean it does not exist. An uncritical image of Swedish culture survives and is bandied about between various subsidy programmes in the EU and institutions of the welfare state.

Even if it is considered outmoded, the nation state does influence large portions of the contemporary art scene. The economy and careers of artists are influenced very tangibly by their nationality, since different countries make different allocations to culture. Government grants to artists determine how the particular nation state is represented in other countries, even if these grants are often given in response to specific requests from these countries.

With its selection of artists and works, Swedish Hearts asks if contemporary art could present a more multifaceted image of the society we live in. The exhibition is also an attempt to examine the collective coda and tacit national self-image of the art world.

New styles and materials

Since the 1990s, a number of exhibitions have featured the theme of Swedish and Nordic contemporary art, in Sweden and abroad. Some have confirmed, while others have aimed to revaluate, the image of Swedish contemporary art. To redefine the content of Swedishness is no easy task. We are referred to the building blocks of collective ideas, myths, lies and ideals, which are well-documented, filed in museums and academically defended. Each exhibition represents an interpretation. National representation is constantly being renegotiated on the art scene and this regeneration has only recently made a mark on cultural publications and institutions. But rarely have, say, post-colonial perspectives been applied when examining what is suppressed on the Swedish art scene.

Art school graduates have, over the past six or seven years, changed that scene, however. New art works are based on experiences that were hardly viable in the art world before, such as being in the Home Guards, or having a background in the revivalist movement. It is not so much the private aspect of the experience that is emphasised. Rather, these artists focus on experiences that tend to be kept invisible. On the margins of the traditional aesthetic field we find Valeria Montti-Colque; her performance installations borrow their imagery from revolutionary movements and popular culture. Another example is Dimitrios Kiriziadis’ works with references to the world of clubbing and an air of baroque Gesamtkunstwerk, that speak to us with sound, colour and smells. A similar form of borderlessness and refusal to conform to cultural norms is described by Lars Mikael Raattamaa in Passing (Sprawl 3). The word sprawl aptly describes the unregulated spreading and growth that is not encompassed by the city’s usual infrastructure, for instance, shacks, industrial areas and allotments.

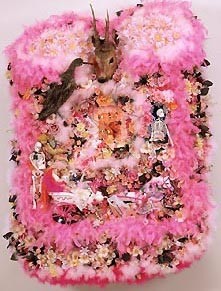

If we look beyond mainstream contemporary art, we quickly discover that this focus on private life in relation to prevailing norms is far from new. However, less marketable themes tend to make artists invisible. Obviously, international exposure does not automatically make a Swedish artist visible on the domestic scene. Anders A, Carlos Capelán and Anna Maria Ekstrand have been working to achieve a more tolerant aesthetic landscape, but have also gathered artistic sustenance outside the Swedish borders. Anders A’s work can be linked to the American west coast and Asian influences , while Carlos Capelán is firmly established on art scenes in the rest of Europe and North and South America. Moreover, Anna Maria Ekstrand’s baroquely sensual installations have been featured in exhibitions aimed at making inroads into the dominating taste. The current discussion on Swedish identity in various contexts indicates that the earlier images or constructs no longer serve their purpose. Swedishness cannot be contained by descriptions such as that in the adverts for Pripps Blå lager or the TV show Sommartorpet about refurbishing summer cottages – other experiences of Swedishness have gained critical mass, and the time has therefore come to redefine Swedishness.

Old rags

In Swedish Hearts, the searchlight is not primarily aimed at potential skeletons in the closet. Instead, the quest is on a more everyday level. The title of the exhibition comes from a line in the old Royal Anthem and from a Swedish TV series. Whereas the Royal Anthem exudes pompous nationalism, the TV soap describes the dramas and intrigues of ordinary middle-class life. Both are based on established images of Swedish identity, one national romantic, one welfare stately. But Swedish hearts contain so much more.

All national historiography strives to enhance the image of unity within the national borders. But what are Sweden’s borders in time and space? Svealand-Finland? Sweden with trading posts in the West Indies and territories in Germany, Poland and the Baltic? Or perhaps the Swedish-Norwegian union? National identity has to be continuously re-learned, but is supposed to be natural and eternal. So why are Finns regarded as immigrants in Sweden? And should the Sami people be counted as Swedes, Norwegians, Finns or Russians? There are many examples of national identities that do not correspond to national borders. The idea of what is “typically Swedish” has, to a great extent, been created by and for an external audience.

“The eternally Swedish” is a myth that encompasses contradictions and half-truths. The question is with whom we identify: the emigrants who left Sweden, or those who stayed behind. In her two-part video work, Andersonville, Kajsa Dahlberg explores the myths around the history of Swedish emigration to the USA. One part is based on Jan Troell’s film version of Vilhelm Moberg’s books about the Swedish emigrants and immigrants and the mass exodus from Sweden to the USA in the dark 1800s, and their dream of a better life in a new country. This glorification is interesting against today’s attitude to economic refugees who come to Sweden in the hope of finding a better existence. In the second part of Andersonville Kajsa Dahlberg uses her own documentary material and looks at the descendants of the emigrants in today’s Andersonville, a neighbourhood in Chicago, and their idea of the “home country”.

As we know, our idea of our origins is not based on historiography alone. Myth usually describes the indigenous people as the owners of the country, tillers of the soil, even as defenders of the household, invisible or diminutive helpers (on Gotland they were called di sma under jårdi, the small ones underground) that people had to stay friendly with. This is one starting point that Tokyo artist Tsuyoshi Ozawa exploits historiographically in My Knowledge About the Dwarf, in which he fabricates ideas about Swedish history and origins out of legends and fictitious archaeological findings.

Is this really a folk costume?

Swedes are blonde nature-lovers, we are often told. A love and respect for nature and the ecological system is good, both aesthetically and spiritually, and nature is often perceived as friendly and an embodiment of positive qualities. Annika von Hausswolff and Juan Pedro Fabra Guemberena challenge this romantic perception of nature in their pictures, where nature is associated with territory, which is defended forcefully, and with death as the ultimate consequence. On closer consideration, nature is often associated with death, in hunting, military drills, or in the idea of woman as nature, a concept Hausswolff deals with in haunting images.

Another object of national pride is the claim that Swedish women are the most equal in the world. The idea that Sweden is world champion at abolishing sexual discrimination is interesting, since the assertion, until recently, only applied to certain aspects of the public sector and participation in the labour market. It has been far less popular among Swedes of both sexes to share alike the less glamorous sides, such as unpaid nursing work and cleaning, in the private domain.

National romanticism did not only engender famous men like Verner von Heidenstam and August Strindberg. In the circle around Ellen Key, artists and radical cultural prominences discussed the role of women and men in society. In works such as Missbrukad kvinnokraft (Misused Women’s Labour, 1896) and Barnets århundrade (The Century of the Child, 1900), Key presented emancipatory ideas and proposed a revaluation of what she claimed were female characteristics (associated with motherhood and care). In the painting Springtime in Hallonbergen (1972), Anna Sjödahl has portrayed the life of women in the suburbs, paraphrasing Edvard Munch’s The Scream. 30 years later, Catti Brandelius delivers another version of women’s suburban life between screaming kids and a snoring husband. She sings, to anyone who will listen: “This was not what Ellen Key, Ellen Key, meant to say.” How much has actually changed? The tapestry by Anders A, with the embroidered slogan “Of course we need a cultural revolution now” aims an ambiguous plea at a collective “us”. Who knows where a cultural revolution, dressed in this very traditional costume, might lead us?

In the essay “We Swedes” in this catalogue, Ximena Narea looks at the career routs for artists who change their nationality, taking her current examples from parts of the art scene with links to the Spanish-speaking world. Many Swedish artists have international careers that appear to have escaped the attention of the domestic art world, possibly due to its preoccupation with development in countries such as the UK, the USA and Germany, and its representatives’ inability to read Spanish.

All the clothes are the same colour

Swedish society is often described as homogeneous. Anything else would be surprising, since the aspiration of the nation state is to fuse its population and territory into a community. In her essay “A people of ice and sunlight”, Ylva Habel presents a background to the national ambition to create a better demographic base in the 1930s, and how this required a broad and popular approach in order to ensure efficient implementation. The long process of developing a unifying national language added to the feeling of national community. With the growth of broadcasting, it became possible to reach more people and create a greater sense of community. Even people who were far from one another geographically could embrace the same ideal looks, clothes, interests, and so on. Modernity made personal development in the service of society a mass-preoccupation – a practice shared by so many people at once, that the dream of the future became a shared dream.

The Social Democratic tendency to confuse equality with likeness (jämlikhet vs. likhet) colours the attitude to what is normal, which, in turn, determines how new members are incorporated in society. Differences and variations have always existed, but have been made invisible, pushed deep into the closet, so to speak. This communal society generated a plethora of popular organisations and movements. Carl Johan Erikson’s photographs and films documenting baptistries used for adult baptism in the Pentecostal Church are traces of a dwindling community. Erikson portrays a phenomenon that many people have experienced but few talk about. It can be hard to imagine that one in seven Swedish citizens in the 1940s belonged to a revivalist church. The Christian Democratic Coalition Party, which had a large following in the Pentecostal Church, was transformed under party leader Alf Svensson into a more conventional party that is not necessarily associated with adult baptism. The subsequent changes of name and focus issues indicate how modernity has also shifted the position of religion in society.

Fia Sandlund is more critical in her study of another community, in her installation The Artists’ Club. Her recordings of telephone conversations with members of this select society demonstrate how gratuitous the criteria are that exclude women from membership. The provokingly banal replies to her questions on who is allowed to be a member expose the paradox of creating a sense of community that is defined and limited by the particular characteristics of the selected.

Chun Lee Wang Gurt’s diptych To be Transported is about family, showing how the family changes over time and with migration to different countries. The work is based on a video recording from her father’s funeral in China that Chun Lee Wang Gurt was unable to attend. Her father was a mayor and head of the police, and his crystal coffin signifies that this is an official funeral. His visibility in public life made him correspondingly invisible to his family. Opposite the video projection, however, is a group portrait where the father is the natural centrepoint of the family. It identifies the people in the video and reveals their relationships around this hub.

Moving to a new country is often associated with dreams of a better life. The magnitude of the venture in relation to the result is illustrated by Snezana Vucetic Bohm’s work consisting of two podiums shaped like bar charts, where a large cleaning trolley is juxtaposed to a small photo of the Chevrolet Impala her father dreamed of one day being able to afford. This coveted car was to be used for annual holiday trips back to the family’s homeland.

Who has the key to the closet?

Exhibitions are always created with a particular audience in mind. The average visitor is rarely mentioned in catalogues, but museums are forever training and fostering their audience with tours and events. Their efforts focus partly on the general public and partly on the professional art world. But who are the individuals that feel comfortable in, or addressed by, the museum? Just by the entrance to the exhibition – but outside the door – stand five casts of human figures. These figures were made by FA+, and they portray the hip hop heroes The Latin Kings, in company with the artists themselves. They remain on the threshold and help to mark the boundary to the exhibition. Their attitude is ambiguous: either they are just hanging out, or perhaps they are hesitant about whether this is the right place for them, if they belong here, or even want to belong.

Swedes are not known for being talkative, but their upright honesty is all the more renowned. The idea of openness and accessibility is important in Sweden. As usual, Stig Sjölund questions some of our most fundamental preconceptions: honesty as a national virtue and the museum as a reliable public institution. A museum is a public space, as critically eyed by its visitors as it is eager to be there for everyone. Sjölund has planted a pickpocket among the museum hosts. No one can be sure that their ID- cards or crumpled love-letters won’t be incorporated into the museum collection. In the same vein, Charles Esche’s essay in the catalogue compares the image of Sweden that was embraced by members of the British radical Labour movement, and the Sweden he encountered as the head of the Rooseum Center for Contemporry Art in Malmö. The dream of an open society was set against the downsizing of the welfare state in the 1900s.

Is this a men’s suit?

Clothes are a signal of social boundaries, ambitions, professions. Who knows, maybe our closets hold unexpected accessories – such as a pair of high-heeled shoes size 44. Is it possible to know for sure whom the clothes belong to? Mattias Olofsson’s installation is inspired by Stor-Stina (Big Stina), Christina Larsdoter, an unusually tall Sami woman who was exhibited as a curiosity throughout Europe. Identifying himself with her outsidership, Olofsson has appeared in various events as a woman in Sami costume and let himself be photographed at audiences with officials in places as widespread as Tonga, the Vatican and Jokkmokk.

Standing our expectations on their head through contextual change is one theme in the works of Loulou Cherinet. Her White Man Series consists of photos of a white man on a visit in Awasa, Ethiopia. He is portrayed in various cafes and bars, at shoe-shiners and in marketplaces, as the artist plays with the concept of the Other. Regardless of setting, the scenario is always the same, the man is the obvious and exotic projection surface in all the pictures. Jannicke Låker’s video 9½ Minutes reflects a more drastic, terrible and comic image of a Norwegian woman, airing her worst prejudices about the Other, and thereby exposing herself.

Many jokes in the former Soviet Union were levelled at the totalitarian regime. In one of these, someone asks rhetorically whose fault it is that things are so bad. Somebody suggests “Stalin?”, and then “Lenin?” and then tries with “Marx?” “No,” the first guy says, “It’s all because of Peter the Great. If he hadn’t defeated King Carolus XII we would all be living in Sweden now.” The joke is a cynical comment on how alliances change. Dejan Antonijevic’s works deal with national boundaries, for instance in the blow-up of an American visa in his Yugoslavian passport with a note stating that he is travelling with his Swedish girlfriend. After September 11, 2001, this would no longer be as obvious an advantage – a Swede is no more reliable than any other European when entering the USA. In Torgny Nilsson’s interactive computer installation the viewer is faced with an equally unpleasant social interaction, in the encounter with various authorities (by inference, this could be the family or the state) that aim direct instructions at the viewer, who can neither guess what is expected of him/her, or create any form of alliance.

Who would wear trousers like these?

Like the rest of the world, parts of the art world are strongly internationalised, and the avant garde of contemporary art sometimes seems to be spread all over the world. Carlos Capelán conveys something of the long-haul traveller’s experience of shifts in time and place in his text-based work Jet Lag Mambo. The feeling of going with the flow, and partially lacking control or belonging, is perhaps a bit frightening, and yet not entirely unpleasant.

So, where do we find the words to describe our identity? Katya Sander has studied the collective spirit in Stockholm’s public toilets by compiling the various appeals, messages and names that have been scribbled on their walls. Perhaps the graffiti collected from these public, yet very intimate, conveniences reveals an underlying self-image.

We all need to go to the toilet, and we are all going to die. Most people grow old first, but since death is taboo in our society, we make old age invisible, to avoid being reminded of death. Ibrahim Elkarim’s black-and-white photographs show old people in their homes. His work in progress, The Autumn of Life, tenderly portrays faces and environments that relate widely different life stories. These pictures do not represent the standardised IKEA homes that one might think all Swedes inhabit. Instead, other patterns emerge, patterns that perhaps engendered IKEA once upon a time. The photos demonstrate that the rooms we live in are an extension of our identity.

Closet – from the French

Anyone who has lived in a country without knowing the official language knows how closely language is linked toidentity. In If You Could Speak Swedish. Esra Ersen focuses on this by asking people at a course in Swedish for immigrants to write down what they would like to say if they could speak Swedish. A video shows the students reading out their sentences after they have been translated into Swedish. In the background we hear the teacher’s voice, correcting their mistakes. Jonas Hassen Khemiri’s piece, National Anathema is a play with this insight into the significance of language. It consists of voices with different dialects and accents that portray various individuals living in Sweden. This polyphonicdrama demonstrates how language conveys identity; no introduction is needed for us to recognise the characters by the way they talk.

Coffee and potatoes, what could be more Swedish? But the image of Swedishness in art is formulated, as this exhibition reveals, not only by Swedish artists. National symbols are notoriously fickle, and are rarely indigenous – on the contrary, they are often imported, as Ximena Narea points out in her text. Traditions stem from so many different places around the world, and from so many social strata, that it appears only practical to institutionalise such a generous mixture, so everyone can feel represented by some little part.

The finale of the exhibition consists of Måns Wrange’s coffee fountain Monument, which ceaselessly pours out coffee for everyone. Like the other works in Swedish Hearts, this is one piece in the constantly changing scenery of what is Swedish. The work also embodies the overflowing diversity of Swedishness and all the experiences that are embraced by the nation’s borders. All you have to do is quickly stretch your cup out to the cornucopia in order to partake of the never-ending flow.

Text from the catalogue by: Charlotte Bydler, Rodrigo Mallea Lira and Magdalena Malm