Swedish Hearts

Swedish Hearts

12.6 2004 – 15.8 2004

Stockholm

Experiences such as being in the home guards or the revivalist movement are not unusual today as the starting point for a work of art. The fact that these phenomena were not valid in the art world before simply proves that we have narrow margins for what is considered normal. These restrictions mean that several interesting experiences remain invisible, since we choose not to talk about them. The silence is not due to censorship but stems from a vague yearning to belong.

The words of the Swedish Royal Anthem, “Ur svenska hjärtans djup en gång.” (From the depths of Swedish Hearts.) written in 1844, convey a solemn nationalism, while the TV series Svenska Hjärtan (Swedish Hearts) describes everyday middle-class life, with its dramas and intrigues. Both are based on established perceptions of Swedishness, be it the 19th century romantic or 20th century modernist kind. But don’t our Swedish hearts harbour more than that? What love, and to whom, and what can be expressed and what is hidden in the depths of our hearts?

Snezana Vucetic-Bohm portrays the dreams vs. reality of a Yugoslavian family who came to Sweden as immigrant workers in the 1970s. With his photographs of baptistries in Sweden the artist Carl Johan Erikson tells of his own upbringing in the Pentecostal Church.

All around Sweden we see artists who engage in a different aesthetic that is neither fastidious nor minimalist, for instance Valeria Montti-Colque or Dimitrios Kiriazidis. These manifestations are obviously nothing new – artists such as Anders A and Carlos Capelán have long been campaigning for a more tolerant aesthetic scene, but have not fitted into the official concept of Swedishness. The emerging discussion concerning a new perception of Swedish identity stems from the fact that experiences of Swedishness other than that of the Pripps Blå beer ads or the DIY TV show Sommartorpet (The Summer Cottage) have gained momentum, and no longer constitute mere exceptions.

On looking closer at romantic depictions of nature, such as the works of Annika von Hausswolff or Juan Pedro Fabra Guemberena, we find another story, one of violence and death. Fia Sandlund’s works demonstrate that the community of various groups relies on the exclusion of certain individuals.

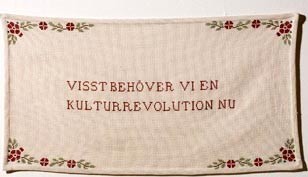

Anders A

© Anders A.

Dejan Antonijevic

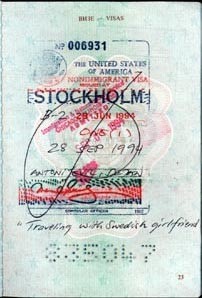

At first glance, Dejan Antonijevic’s works appear plain and simple. The presentation is often terse and the media used is always some form of photography; spatial installations or simply photos mounted on a wall. Looking more closely, however, the pictures themselves prove to be highly complex and reveal a restrained and controlled world full of contradictions.

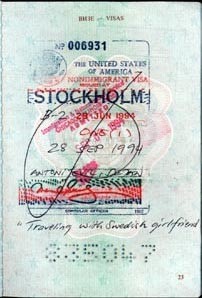

Travelling with Swdish Girlfriend, 2004

© Dejan Antonijevic

Dejan Antonijevic attacks the preposterousness on which we found our preconceptions. He exposes their weakest links and breaks them down into absurd and isolated phenomena. An enlargement of his Yugoslavian passport shows a large American visa issued in Stockholm on 28 September 1994, with a hand-written comment by the embassy official: “Travelling with Swedish girlfriend”, just below the visa stamp. What does this mean? In 1994, when the visa was issued, the interpretation would have been different from today – and this is what the work is about. In 1994, the note would have served as a slightly bizarre assurance that the traveller would not defect to the USA. This enlarged visa would have indicated a tacit agreement between the USA and Sweden, a Western hegemony to which the artist/passport holder did not necessarily have access. His Swedish girlfriend did, however, and this circumstance is what the picture reveals.

Looking beyond what is revealed in the picture, it is not only about a certain type of exclusion that affects the individuals barred from the Western hegemony. The work dates from 2002, the year after the terror attack against the World Trade Center in New York. This is the context of the work, in other words. Today, having a Swedish girlfriend is no longer a guarantee for the reliability of the traveller, simply because she herself is not necessarily eligible for a visa to the USA on account of her Swedish citizenship. Power structures change, and with them the threat scenarios and demarcation lines for the other.

Page A2 Dagens Nyheter 12 September 2001, a work from the same year, raises the question of what choices lay behind the layout of the first spread of the broadsheet the day after the terror attack. A picture where one of the WTC towers is penetrated by an airplane is shown alongside an advertisement with a smiling woman mixing pancake batter in a nostalgic pastiche on an American domestic 1950s setting. Here, Dejan Antonijevic points at the absurd correlation with an actual condition: The picture of the tower and the advertisement form two columns with proportions resembling the twin towers. The equation obviously does not tally and reveals the fragility of our perception of the Western hegemony and the remarkable constructs of identification on which it rests.

Rodrigo Mallea Lira

Catti Brandelius

The use of humour and fond observation to reflect the discrepancy between our dreams and the reality we live in is typical of Catti Brandelius, alias Miss Universe. What was Ellen Key thinking as she sat in the Strand manor and wrote down the ideas that have so profoundly influenced the situation of women in Sweden? What were her dreams and hopes for the future? Miss Universe walks with her pram through a Stockholm suburb and considers the contrast to her own life with screaming kids and a snoring husband, and has to admit that “This was not what Ellen Key had in mind.”

Performance on ferry between Karaköy and Kadiköy, Istanbul, 2003

© Catti Brandelius

Photo: Fatos Ustek

Miss Universe was created when Brandelius was at the University College of Art, Design and Crafts in Stockholm, and soon developed into the female role model she lacked. Miss Universe rules the world, not passively by being elected on account of her beauty, but by electing herself the ruler of the universe who refuses to be nice or say the right things at the right time. She is a self-assured woman who makes no apologies for pointing out injustices, nor, for that matter, for straying beyond the borders of political correctness. Just as her subjects can vary from suburban life to major political events, Miss Universe also uses any means she finds suitable, with a predilection for things that are readily available. Her humour breaks through the barriers between art and audience and helps to tear down the wall raised by exaggerated veneration for art or museums. She creates a composite form of music, performance, spoken word, tap dancing and agitprop. The Ellen Key video and other songs such as På tunnelbanan (On the Underground) evolved out of these performances, as a kind of music videos for her own tunes. På tunnelbanan is a comical and moving portrait of the people on an underground train, uncensored and reflected in Miss Universe’s stream of consciousness.

Brandelius applies a similar humorous and respectful approach in the star portraits of her Hero Suite (2001). These framed, diary-like, illustrated texts celebrate selected role models such as Elvis, Jesus, Selma Lagerlöf and the actor Reine Brynolfsson.

Magdalena Malm

Carlos Capelán

Carlos Capelán is a link between the Swedish art scene and the artistic preoccupations and trends of the international avant-garde. Born in Montevideo in 1948, he is one of the artists who in the 1980s turned towards a broader international context. He has been represented at numerous international exhibitions in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the USA and Europe, including the biennials in Havana, São Paolo and Kwangju. In the context of international shows, his works are obvious contributions to the debate on globalisation, international communities, language and power. His change of scene probably made a virtue of necessity: Sweden’s art scene was too preoccupied with scrutinising Swedishness and launching it abroad, to perceive Capelán’s questioning of the claims and demands of the national state on the individuals living within its borders.

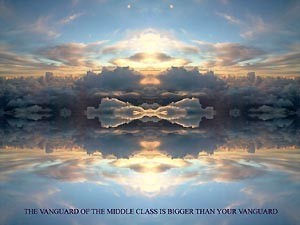

The Vanguard of the Middle Class is Bigger Than Your Vanguard, 2004

© Carlos Capelán

The environments – including museum halls, living rooms or darkrooms – that the artist has used are literally or figuratively places where we develop pictures of people. His shows consist either of pictures of bodies, or the knowledge that these environments represent. The imagery of the institutions obviously has a favoured position in relation to society’s image of itself, the national identity. Museum art collections are the collective value of science to the nation. Who, and whose values, are prioritised in the nation’s cultural budget? One should never underestimate the recognition implicit in finding that one belongs to an ideal target group, in recognising artists and aspects of the taste promoted by museums and concert halls. Capelán justifiably criticises the image that institutions present to audiences to identify with. People’s self-image is only partially of their own choice, and the weight of the official culture adds to other pressures on that part of the individual’s identity that other people attribute to her.

Equally important, but less obvious in public debate, is the division between collective commonsense and individual feelings. This order is maintained in daily life within the domestic sphere in concurrence with the public and collective sphere. This has been focused by Capelán in various contexts as an artist, curator and writer. The contrast between Capelán’s printed texts in catalogues or anthologies, and works written by hand with body fluids, could serve to demonstrate the material base of conveyed knowledge. Anyone who rhetorically wishes to present the current state of affairs as the natural state, readily employs nature in a literal sense. Biological arguments often form the base for absolute claims on territory and cultural identity. Since the very birth of a person can be cited in demands of that kind, it is only logical that Capelán uses materials such as breast milk, water and earth to demonstrate how negotiable blood relations and birthright actually are.

Charlotte Bydler

Loulou Cherinet

A documentary and biographical tone pervades in the works of Loulou Cherinet. They always include actual people in more or less arranged situations. She makes no secret of the fact that the situations in her films and photos are constructed, but the difference between reality and image is not that great. The actors in her films always play themselves, even if the situation is arranged, but it may not differ much from the situations and the parts they – and the viewer – normally have in the social space.

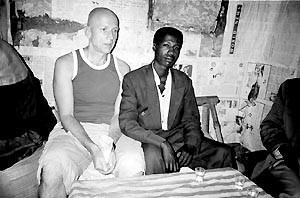

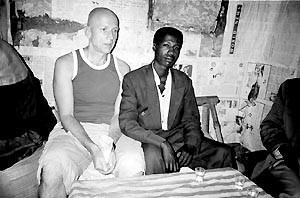

White Man Series, 2000

© Loulou Cherinet

In the video White Women (2002), for instance, the setting is a dinner at a large table where all the guests, all men of African origin, are filmed with a rotating camera in the centre of the table, as they sit dressed in striped sailor tops discussing their experiences of white women.

In the serene and remarkably charged photos of her MAN SERIES (2001) the subject is instead a white man whom Loulou Cherinet happened to meet in Ethiopia. She takes him along to various cafes, arakebets (bars that serve home-made liquor), zukens (kiosks), shoe-shiners and marketplaces in Awasa, where he is the indisputable centre of attention for all the others. Regardless of place, the scenario is always the same, an electrified atmosphere surrounding this white man. In the pictures he is the dazzling, obvious and exotic surface for their projections.

In both White Women and the MAN SERIES, as in most of Loulou Cherinet’s works, it is significant that the relationship between the depicted people and the viewer feels unsevered. You can never really say that the artist’s presence is noticeable in the image, since the depicted appear to ignore the camera, and therefore, the viewer easily slips inside the picture. It feels like getting very close something the artist wants us to see or hear, but which she does not want to present herself or state out loud. Through these unexpected openings into the pictures, created by documentary dramaturgical means, she opens up the situations that the pictures relate to the viewer. This is an equilibristic play with shifts in perspective and perception both within and outside the picture, two positions that, in Loulou Cherinet’s case, always seem to be two sides of the coin.

Rodrigo Mallea Lira

Kajsa Dahlberg

Kajsa Dahlberg’s works focus on the relationship between the narrative structure and the material she uses (almost always film of one kind or another). In Andersonville (2004), a video work in two parts, Kajsa Dahlberg explores a community constructed on the idea of national heritage. Andersonville is an area in north Chicago with a Swedish museum and many shops and restaurants offering various forms of “Swedishness”. Like so many cities in the USA, Chicago is divided into several territories characterised by different nationalities. Chicago is a nation of nations, where the Swedish nation also has a given place. This is only to be expected, in view of the fact that there were more Swedes in Chicago than in Gothenburg around the turn of the previous century.

Andersonville, 2004

© Kajsa Dahlberg

Videostill

In Andersonville Kajsa Dahlberg looks at the perception of the “home country” among emigrants and their descendants. In Wilhelm Moberg’s novels the emigrants are always pining for the mother country. Is it the same in Andersonville today? In the first part of the video work Andersonville Kajsa Dahlberg has used material from Jan Troell’s film of Moberg’s The Emigrants, to make a short trailer. In The Emigrants the fiction visualises a story that is familiar to many. But neither Moberg nor Troell are able to summarise the entire emigration. The 1850s emigrants are very different from those of the 1930s who got jobs through agents on the large transatlantic ships. Using the trailer format, Kajsa Dahlberg gives this sprawling experience an exciting and dramatic form. The trailer is an interesting format in itself, which sums up a story without conveying more than a hint. The Andersonville trailer is a signature for the mass exodus to the USA, and plays with the image presented by The Emigrants and how the event is perceived in Andersonville.

The second part of Andersonville, also a short film, is based on Kajsa Dahlberg’s interviews with people who earn their living in one way or another by being Swedes in Andersonville. The film format mimics the credits section that usually concludes a film. The frame is divided, one half showing excerpts of interviews following on one another, while the other shows the title of the work and the names of absolutely everyone who participated in it – all the interviewees, and those who were edited out. It serves as a space for everything that was not included in the film, in real life, anything that was not sufficiently relevant, interesting or important – this is the reality that falls outside the certified version of history.

Rodrigo Mallea Lira

Anna-Maria Ekstrand

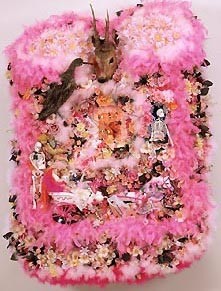

Anna-Maria Ekstrand (b 1966) lives and works in Gothenburg and belongs to the generation of artists who started exhibiting in the mid-1990s, a time when many (women) artists were described as “girl’s room artists”. This soubriquet pointed to the way in which they identified certain materials, colours and themes as having a strong impact on children’s upbringing, and especially on the formation of gender identity. Later artists have used pink, soft, childish and erotic princess accessories in performances and enactments of their artist persona. Anna-Maria Ekstrand does not necessarily belong to this category, however.

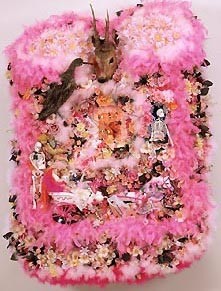

Box, odaterad

© Anna-Maria Ekstrand

In a work titled Anna-Maria Marries Poseidon (1993) she took on the muscular and archaic sculpture of Poseidon by Carl Milles which stands in a fountain at Götaplatsen, in the midst of some of Gothenburg’s most prestigious cultural institutions. In a combined happening and installation under a marquee, the artist and the god appeared in clothes fit for a royal wedding (or carnival). So, was this a recycling of the symbolic power of the classic myth, a satire on the self-image of Gothenburg’s highbrow cultural elite, or (and?) a feminist enactment reclaiming the public arena? This is typical of the ambiguous economy of desire in Anna-Maria Ekstrand’s works: it is never clear if the aesthetic belongs in a particular context or norm, or in the service of either sex. Sexuality is linked with death, love with violence, femininity can be expressed as something tiny and warm, or just as readily as something hard and ragged.

Some of her works sprawl with a myriad of objects as though in a parade or an intricate plantation. The cacophony of rearranged fleamarket bargains, ornaments and toys that are nonetheless inserted in a structure, resemble baroque altar arrangements or votive images, objects used to placate the higher powers. Erotic key words such as “Foxy Lady”, skeletons and maimed dolls lavishly applied with blood red place the compositions firmly among the wicked clowns and androgynous vampires of horror movies, although with a sharply dissonant tone of cuteness.

Anna-Maria Ekstrand is an important counterweight to the blonde minimalism of Sweden’s official image. She appeared in this role for instance at the exhibition Swedish Mess, when Stockholm was Cultural Capital of Europe in 1998. Her imagery conjures up a new world – a limited context in which both the representative and shady sides of our common world are subjected to new laws and rules. The new world logic is not entirely clear among all the shifts of significance in the pandemonium of colours and shapes. But in the confusion and mass effect, this Utopia grabs our attention, disturbing and imposing in thousands of ways. The countless repetitions become a yardstick for the urgency of the matter.

Charlotte Bydler

Ibrahim Elkarim

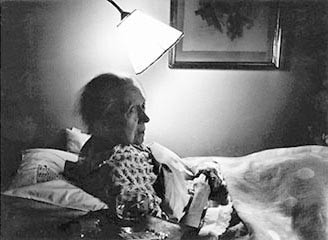

A photographer who documents people’s lives with a social agenda is not entirely unlike the anthropologist who travels to and returns to the same place at certain intervals. In that sense, the photographic works of Ibrahim Elkarim belong to a genre that includes the film-maker Stefan Jarl’s trilogy about Stockholm’s mods, Jens Jensen’s photo books about Hammarkullen in Gothenburg, and Stig T Karlsson’s Sverigeresan: ett sommaralbum från 1980-talet (The Sweden Trip: A Summer Album from the 1980s). The tension between traditional life and modernisation are central to this genre. That does not mean, however, that it is linked to a specific nation: Elkarim started his art studies in Darmstadt in West Germany (1964-65) and later went on to the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm.

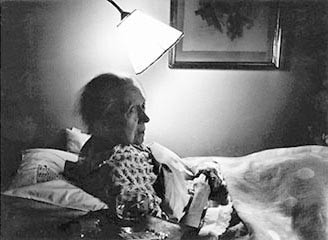

From the series The Atumn of Life, 1984-85

© Ibrahim Elkarim

Judging by the image flow of the mass media, one could easily get the impression that a person who is not visible in working life does not exist – giving retirement an ominous ring. On the whole, old age and the need for assistance do not fit in with modern society. The rational industrial sector – not to mention the rational society – sees no innate value in having long professional experience and knowledge, that’s how fast technical change takes place in working life. Life in another, less urbanised and pre-modern Sweden is a thing of the past that is removed from contemporary life like a strange museum exhibit. One media context in which older people do figure, however, is in reports of neglect, a result of how responsibility has been delegated away from the family, without being taken over by society.

Ibrahim Elkarim’s photos do not focus on that kind of disastrous occurrences; on the contrary, they exude an intimacy with the motif. House fronts, faces, interiors and parks have not been monumentalised by being blown up to exaggerated proportions or depicted with extreme sharpness. Yet the attention to the motif has given them the status of historical monuments – or anti-monuments.

The domestic interiors is, of course, a genre in itself. Common varieties are the artist’s home, or the family idyll, or the home that guarantees that the inhabitants are typical representatives of a certain cultural stratum. In a biographical interpretation, the interior relates the inhabitants’ resources and taste. The home serves as a representative showroom, the result of decorating, a redecorating project in a TV show. Official public taste gives way to private taste in the private sphere. The domestic environments and people in Elkarim’s pictures are far from being the paragons of good taste and aesthetic education that Svensk Form and IKEA prescribe. The photos do not aim any criticism at these institutions – but they do demonstrate that the Swedishness associated with these companies is out of touch with large parts of the Swedish population.

Charlotte Bydler

Esra Ersen

The Turkish artist Esra Ersen was born in Ankara in 1970 and now lives and works in Istanbul. Her works often deal with identity, how it is created and changes. She employs various media, from photography and video to installations, and a feature of her work is that she bases it on the place where she happens to be.

If you could speak Swedish…, 2001

© Esra Ersen

DVD

In her work I Am Turkish. I Am Honest. I Am Diligent (1998) Ersen worked with a group of pupils in a school outside Münster in Germany. The children wore Turkish school uniforms for a week, and meanwhile wrote down how they experienced wearing this different costume. Their notes were then transferred directly to the uniforms and exhibited in the school. In this work the change of identity and experience is then conveyed to others by being exhibited.

Ersen’s works often express her social commitment. In This is Disney World she filmed street children in Istanbul. As in most of her works, however, she is not a detached reporter but participates in the process by making contact and directing the questions, although without appearing personally in the photos. With her presence and sensitivity Ersen portrays people and situations and brings us closer to those we are looking at, while conveying an understanding of the situation in which they exist.

In 2001, Ersen was living in Stockholm, where she produced the work If You Could Speak Swedish. She attended a course in Swedish as a foreign language and asked the other participants to write in their own language – be it Chinese, Russian, Bengali or Arabic – what they would say if they could speak Swedish. Their responses span from political statements to emotional outpourings. Their sentences were then translated into Swedish, and the work consists of a video that shows people reading their own sentences in Swedish. Off-screen we hear the teacher’s voice correcting their pronunciation.

If You Could Speak Swedish. demonstrates the problems of translating, and the vulnerable state people are in when they come to a new country to live, but can’t express what they want. Set against the fragility and honesty of the replies, the correcting teacher’s voice appears almost brutal. The work gives an insight into the enormity of the task of building a new life for oneself as an adult.

Magdalena Malm

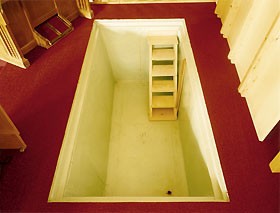

Carl Johan Erikson

Carl Johan Erikson’s works spring from his experience of small town life, and, more specifically, from the artist’s own past in the revivalist movement. He belongs to a relatively young generation of artists who use their own experiences in their work, but not so much in the form of diaries as in more universally relevant discussions. Erikson transforms his personal history into works that are both quirky and analytical. Just as people often keep quiet about their rural background when they move to the big city, it is no secret that Christianity has not been a particularly popular theme in the upper echelons of art.

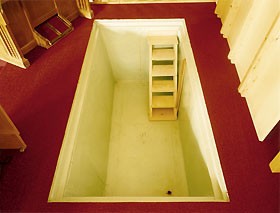

Tank nr 27, 1999

© Carl Johan Erikson

A few years ago at Arlanda Airport, one could see a small, home-made sign with blue neon letters proclaiming: Wake Up (1999). In the profane, anonymous airport environment this message had a more general meaning, but it also incorporates the revivalist voice that emerges through the noise. The following year, another sign hung near the exit, with the reassuring message He is coming soon (2000). This could signify a brother, son or lover returning from abroad, but beneath the surface, of course, is the message of the return of the Messiah. It appears slightly surrealistic that he should turn up at Arlanda and come to us after passing through “Nothing to Declare”. In this way, Erikson juxtaposes revivalist faith with the ideal modern secularised society, while leaving room for more everyday interpretations of his works. But if the coming of the Lord may appear distant in the meeting-point between the 20th and 21st centuries, it has not been so for long. In the 1940s, some 13 per cent of Swedes belonged to one of the revivalist churches. In no other part of the world has it gained such a strong foothold as a popular movement.

In the photo series Tank No 1 – Tank No 44 Erikson had developed the revivalist theme while conducting a veritably archaeological study of a culture in decline. The series portrays a number of baptistries used for adult baptism. To anyone who has been involved in this tradition, they probably appear familiar, but to those with other terms of reference the images also hold an element of terror. The lids over the pools are leaned against the nearby wall, and the pictures contain a threat of being closed in and left to one’s fate in one of those abandoned “graves”. But this fear also says something about our fear of the unfamiliar. Although a large proportion of Swedes have belonged to the revivalist movement, the baptistry is an unfamiliar image. Erikson reverts here, as in earlier works, to highlighting something that is both well-known and hidden.

Magdalena Malm

FA+

Today, many artists engage in luring their audience to see their surroundings in a new light, perhaps to take a closer look at their neighbour or their usual supermarket. The focus of this relational aesthetic is on the framework, the actual familiarity, or the enactment of what we call art, rather than a particular object or monument. In the 1990s, more and more artists started working on object-less projects financed by more saleable art, day jobs or grants and scholarships. When FA+ embarked on this road it was not particularly wide-spread in Sweden.

TLK, 2004

© FA+

Photo: Gustavo Aguerre

In various group projects under the FA+ signature, the artists Ingrid Falk (b 1960 in Stockholm) and Gustavo Aguerre (b 1953 in Buenos Aires) have seized the contemporary art stage, not least with the aim of problematising the concept of the lone genius and the Great Artist. These pioneers in the field of site-specific art have often applied a provocative, activist approach. At a release party for the magazine Tidskriften 90tal (1997) FA+ organised an admittance where guests could choose between a VIP lane for “Stockholm’s cultural elite” and a lane for “immigrants/ordinary people”. Both queues led to the same door and box office, but those who considered themselves to belong to the cultural elite were questioned by the bouncers about their origins, income and occupation. Those whose answers were not up to par had to join the “ordinary” queue. At the Italian pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1999, FA+ presented a lunch on the theme of Contagion – an international, cross-disciplinary project that had been launched in 1995 to besmear national purity and delete it in various joint projects.

The rumour of the death of political art is greatly exaggerated, as the work of FA+ over the past 20 years serves to prove. FA+ has examined social charity, humanitarian aid and the effects of the European Union on Swedishness and other identities. In 2001, they took part in the Biennale in Buenos Aires with The Toaster, a title that alluded not only to the motif and material – toaster and toast – but to electric torture. It is in the nature of things that commitment to specific issues is not considered cool, and can therefore be hard to express in an artistically detached manner. Irony and humour, however, can lead to a certain detachment, albeit at the cost of coolness. With these means FA+ puts the integrity and dignity of both artist and audience to the test. Their challenge demands a response.

Charlotte Bydler

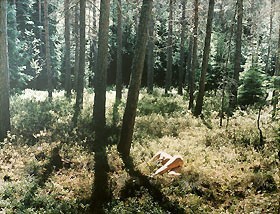

Juan Pedro Fabra Guemberena

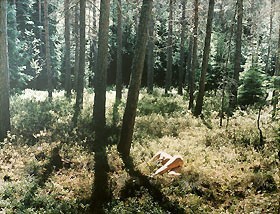

Nature is undeniably presence in all Juan Pedro Fabra Guemberena’s works. Everything that takes place in the pictures, all enactments in his video works and photos, are set in the countryside. He leads our thoughts to national romantic ideas of soulful nature imbued with meaning. But while nature is an immense projection surface for longing, dangers are lurking in the impenetrable dark forests, the oceans and overwhelming vast expanses. Nature is a mighty challenger that provides only temporary refuge, it never ceases to put up resistance, while simultaneously waiting to be conquered and explored. In these landscapes, Juan Pedro Fabra Guemberena places his figures. In the video work “True Colours 2” (2004), little scouts are seated round a campfire, alert and fully engrossed in making tools that appear to be crucial to their survival. Now and then, their concentration is interrupted by an almost inaudible noise coming from somewhere in the surrounding dark forest, they stop what they are doing, only to quickly resume their task.

True Colours, 2002

© Juan Pedro Fabra Guemberena

C-print.

Courtesy Brändström & Stene.

The video work “True Colours” (2003), precursor to “True Colours 2”, includes real soldiers in uniform and full gear. All they seem to do is wait quietly – as they appear to merge with the bleak Gotland landscape. They sink into the dense undergrowth of the sloping chalk cliff and move with it as it sways in the wind. The purpose or task of the soldiers seems unclear, at least it is impossible to see what they are doing. They sit, they stand, they lie down. But are they on alert? Are they waiting for the enemy? Is the countryside around them theirs? Have they invaded it? They appear slowly and almost imperceptibly to become one with the landscape surrounding them. Nature gobbles them up ruthlessly, until, as in fairytales, there is no difference between the living and the dead. The soldiers increasingly resemble some kind of phantom figures of the forest, like trolls or spirits.

The relationship to the romanticist exploitation of nature is complex in Juan Pedro Fabra Guemberena’s works. He obviously has a fascination for, and a profound knowledge of, the imagery it has produced. At the same time, there is a sharp criticism against romanticism and its contribution to the construction of nation and the resulting perceptions of identity and belonging. Juan Pedro Fabra Guemberena gives nature, or territory, a frightening body that needs to be both defended and conquered with violence.

Rodrigo Mallea Lira

Annika von Hausswolff

Annika von Hausswolff is one of the Swedish artists who won broad international acclaim in the 1990s. She works with meticulously arranged photographs, often using the body, imprints of the body or memories that can be related to physical experiences as her subject matter. Hausswolff takes familiar motifs and imbues them with new meaning. Therefore, when we see one of her pictures for the first time, we sometimes think we recognise it, that we’ve seen it before, but something isn’t quite right, a detail shifts the expected association and twists the image into something else. Hausswolff once said, “My images are a platform for projection, a tool.”*

Back to Nature, 1993

© Annika von Hausswolff

Photo: Alf Pergeman

The series A Study in Politics (1993) is one of Hausswolff’s earliest works. It consists of six photographs of battered women, or close-ups of bruises from forensic reports. The pictures are cropped into ovals, to signal that they belong in the genre of family portraits, and the people in the photos are masked.

In her next work, Back to Nature (1993), Hausswolff moved on to working with arranged photos. This series shows more or less undressed female bodies that lie scattered in nature. The photos were produced while Hausswolff was at the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, and are strongly influenced by thoughts and ideas on feminism and social power structures in society. These pictures, together with the title, are an (abominable) critique against a culturally more or less explicit way of regarding woman as nature. In Back to Nature woman is reunited with her element. These photos have become veritable icons of Swedish 1990s art, with their clear references to art history (e.g. Women in a Landscape by Richard Bergh) twisted into a scathing criticism against the way women are portrayed. The fact that this series has become so famous even though it has only rarely been exhibited, is probably because it reveals something about the romanticised notion of Swede’s relationship to nature, where the longing and nearness to nature represent both a temptation and a threat.

In many of Hausswolff’s later photographs people are entirely absent or shown with averted faces. This does not signify that the artist has abandoned her explorations of human conditions or relationships, however. Instead, there are traces of people’s activities, in the form of everyday items such as chairs, doors or dust, or in the form of memories, as in the work The Memory of my Mother’s Underwear Converted into a Flame-Proof Curtain (2003). The absence is so compact that it materialises into an unavoidable presence.

Magdalena Malm

* From an interview by Marianne Torp, in the catalogue Room for Increased Consciousness of the Parallel Day, Statens Museum for Kunst, 2003

Dimitrios Kiriazidis

Dimitrios Kiriazidis is based in Gothenburg and graduated from the Valand School of Fine Arts a few years ago. From an early age, drawing was his crucial means of handling major changes in life as he moved between Greece and Sweden. His way into art went via graffiti, which got him interested in getting his message across. His works demonstrate a strong desire to communicate, an unusual element in Swedish art. Unlike the more minimalist art tradition which is deeply entrenched in the official Swedish art taste, Kiriazidis is never afraid of approaching the baroque or the sentimental, but without losing his sharpness.

Untitled, 1998-

© Dimitrios Kiriazidis

C-print

Pågående fotoserie.

It is no coincidence that Dimitrios Kiriazidis, aside from being an artist, also works as a DJ. Kiriazidis involves the audience in an experience based on rhythm and a perception of space, where viewers gradually come to reflect on what they are encountering. One of his works consists of low-frequency noise in a tunnel (1999) – most of his works are untitled – something that is experienced equally with the body and the ears. In one of his most beautiful and most theatrical works (2002), the viewer enters a darkened room with a dramatically lighted heart made of real roses in the middle. The room is filled with music from an unidentifiable source, and the division of the room makes it resemble an orthodox iconostas. The work balances on the brink of kitsch, but dares to hover there, and in that way achieves an effect that deeply affects the viewer.

In another work (2001), where Kiriazidis has filmed a contact print of photos from his life, rhythm is again central. Like an eye, the camera pans the pictures from parties, travels and daily life. It stops at details, returns to the previous picture, and so on. The video is projected on a wall in a small room where the viewer becomes a part of the picture space and is almost physically carried along by the camera movement. The viewer is invited to enter another person’s memories and private experiences.

Magdalena Malm

Jannicke Låker

Jannicke Låker was born in 1968 in Drammen, Norway, and lives in Berlin. She works primarily with video, describing embarrassments, painful situations that we try to avoid and do our utmost to suppress when they nevertheless arise. She reveals them fearlessly to the camera: a male actor’s pathetic inability to act angry and menacing (Sketch for a Rape Scene, 2002), or a Norwegian businessman’s candid and conceited racist prejudices (Beautiful People #1, 2002). Låker’s frequently ruthless stories make audiences squirm in their chairs when she includes them in the narrative and shows them exactly what they don’t want to see. With wry humour she presents people in cruelly manipulated and unpleasant situations. She is not only an observer, however, but often participates in the story and thus cannot remain an impartial critic.

9 1/2 minutt, 2000

© Jannicke Låker

Videostills.

Jannike Låker’s video works borrow their aesthetic and composition from the home video and the documentary. Her work No 17 (1997) exists at the very intersection of these genres. A woman picks up an American tourist in the street and asks him to come home with her. He accepts, and agrees to let her film him all the time. Mixing flattery with commands, she gets him to take off his shirt and dance for her. When he eventually protests she throws him out on the street with no further ado. From a Scandinavian perspective, this excruciating film nevertheless delivers a refreshing contrast to the stereotype image of Swedish women that we encounter all too often. Interestingly, when the work was shown at the Whitney Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, it was the complete naivety of the American that became the focus of interpretation.

9 ½ minutes is a Norwegian woman’s video letter to her husband who is an international aid worker in Africa. The video starts with beautiful images of the Nordic countryside and goes on to show an interior with a dinner table set for two. The camera is placed on the husband’s side of the table and the woman speaks lovingly to the camera, to her husband, but also to the audience. Låker plays with perspective, and we become both onlookers and peeping-toms, watching something that isn’t intended for our eyes. After a few glasses of wine, her real feelings start to come out. She is jealous of a black woman her husband has mentioned that he has met. The woman gets more and more aggressive, loses control and reveals her desperate jealousy and her racism.

The brutal humour of 9 ½ minutes exposes what must not be said. The loss of self-control is central, and this is what makes us involuntary voyeurs laugh even though we wish we hadn’t been watching.

Magdalena Malm

Valeria Montti-Colque

Valeria Montti-Colque completed her studies at the Royal University College of Fine Arts in Stockholm in 2003, but her work is almost entirely free of influences from the art world that the school represents. Montti-Colque’s works reside in a borderland between performance and capoeira, a Brazilian martial art dance. Her imagery uses multi-layered graffiti, spiritual symbols, the Rastafarian colours yellow, red and green, and portraits of heroes and spirits. Titles such as Samba duro, Where doves fly and I know a place describe this borderland between dreaming, dance, music and resistance. One of her recurring metaphors is the soldier, the image of a fighter who shows the way to the promised land, which might be possible to reach in this life, or sometimes only hinted at as a possible redemption, a salvation beyond death. Other metaphors taken from history are the never-colonised Abyssinia/Ethiopia, and, not forgetting, all those who have demanded respect for their human dignity in the face of the transatlantic slave trade.

Comiendo gemelãon, 2001

© Valeria Montti-Colque

Teckning

On the pedigree chart of modern society – and avant-garde art – the French Revolution and the Enlightenment are often upheld as basic experiences and origins. The ideas of liberty, equality and brotherhood formed the principle of the equal worth of all human beings regardless of origin, assets or sex. It also became the basis for a modern concept of art that made it possible, as in other areas of society, for everyone to discuss and evaluate artistic work.

But there are still revolutions waiting to be fought, postponed by the Euro-centric Enlightenment, and by its critics. Colonial politics are only one example of the reluctance to respect the democratic rights of all people in practice. To give the impression that things have changed for the better, the colonialists and historians have excluded people and cultures that were not considered representative of democracy and high civilisation. If an artist cannot afford to use expensive techniques or travel and work abroad, she does not fit into the local modern art institutions’ idea of essential art and is thereby excluded from the historiography. And since the Swedish art scene has centred on the prevailing historiography – the rationalism of the Enlightenment and national romanticism – it was hard to get anyone interested in issues of racism and colonialism.

Against this background, the various historical warriors and camouflage patterns in Montti-Colque’s paintings are part of a general strategy to gain recognition for cultural liberty and rights. The camouflage costume represents a de- and re-identification. Here, a martial art can look like a dance, and the names and appearances of western and central African deities can merge with Catholic saints. In this way, freeloaders sneak in under a historically legitimate guise.

Charlotte Bydler

Torgny Nilsson

A red thread runs through Torgny Nilsson’s work, often tainted by his black and bizarre humour, his questioning of authority, be it a government agency, a workplace, a group, or the family. His works always relate to society in one way or another, either by describing how it functions, or by actually letting it interact with his work.

Gallery as Pigsty, 2003

© Torgny Nilsson/BUS 2004

Photo: Torgny Nilsson

In an untitled interactive work from 2003 (most of his works are untitled), Torgny Nilsson lets four colossal faces, like genies from the bottle, float freely in space and address the audience in different ways. These spirits seem to demand to be obeyed at any price and try to capture the viewer’s attention with various questions and statements that all relate to three light bulbs, one red, one green and one blue, on a podium between the viewer and the giant spirit face that is currently speaking. The face orders or requests the viewer to press a certain light bulb, or not to press it, but the moment the viewer acknowledges the request (whether or not the request is fulfilled) the face changes into another of the three, and the viewer is held accountable for his or her choice. Suddenly, what appeared to be a simple situation with a predictable chain of events is not so simple any more. There is an answer to every button pressed, and they are evaluated not only in terms of good and bad, right and wrong, but with opinions about the viewer’s features and character. The object that a work of art usually is, here becomes the subject, while the viewer becomes the object and is subjected to an incoherent chain of orders following on orders that he/she is predestined to fail to fulfil.

In Torgny Nilsson’s solo exhibition at Galleri 60 (the student gallery), just before he graduated from the Academy of Art in Umeå in 2003, he rebuilt the gallery into a fully functional pigsty, as a comment to the situation that the art world offers the artist. The result was a bizarre play with association. The Swedish expression to “work like a swine” here became a description of the work an artist invests but which is never justly rewarded. Similarly, the saying “cast pearls before swine” describes the unfairness of the relationship between the artist’s work and how it is received in the social space. The situation surrounding art is not only a place where Torgny Nilsson positions his work but becomes a way into and out of it, the work becomes an extension of the social space and the structures on which it is built.

Rodrigo Mallea Lira

Mattias Olofsson

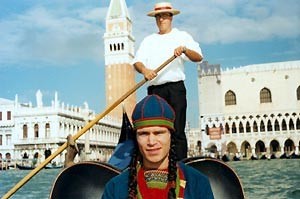

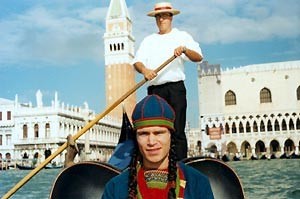

Christina Catharina Larsdoter never stopped growing. She lived between 1819 and 1854, and her life and experiences of being exhibited throughout Europe have been documented by Åke Lundgren in his book Långa lappflickan: sägnen om Stor-Stina (The Tall Sami Girl: The Legend of Stor-Stina, 1981). Stor-Stina, as she was called, has also inspired Mattias Olofsson’s (b 1973) series of performances and photo documentations. In false black plaits and a Sami costume bought at an auction, he has borrowed her identity to explore the outsidership of having an unusual appearance. He has travelled in the guise of Stor-Stina to places such as Tonga, Copenhagen, Venice and the Vatican and requested audiences with secular and spiritual leaders.

Venezian Style Stor-Stina – Gondola Ride, 1999

© Mattias Olofsson

Photo: Mårten Åhsberg

The deviant attracts attention and occasional sympathy, but is usually interesting only to the extent that the deviation from the expected serves to confirm the norm. The artist’s personal biography and his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Umeå do not help to explain his choice of alter ego – it is not a quest for authenticity in relation to his ethnic roots. But one does not need to be of Sami origin to feel an interest in her fate. However, an extra dimension in Mattias Olofsson’s project is that it engendered a co-operation with the artist and Sami craftsman Lars Pirak in Jokkmokk (2003). Out of this co-operation Mattias Olofsson has developed his own narrative imagery.

The artist role itself belongs in a gallery of odd characters and roles. The idealised image of the creative genius incorporates elements of outsidership and exoticism, a life poised between social acceptability and inspired madness. To the extent that income, dress style, working hours and family life can be controlled, an artist can nevertheless choose the degree of outsidership. For people like Stor-Stina, her body barred her from that choice. Religion or sexual preferences, the things that influence what we do and what we think, may seem to be less visible parts of our identity. But these things are revealed to the people around us in the way we arrange our lives. That is when we encounter attitudes relating to “abnormal behaviour”.

Those who defend a normative taste and lifestyle may even feel threatened by discovering that outsidership can also unite people, engender new communities. It is one thing to be odd in a permanent way. But it also causes uncertainty among people when someone like Mattias Olofsson refuses to choose things like the colour of his clothes, his sexual identity or place of residence. That is also a way of exceeding the limits and norms for what is reasonable and to go too far. To say yes to more than what is strictly necessary is perhaps to indulge in excessiveness, but the very multitude encompassed by normality also demonstrates that it is anything but natural or eternal.

Charlotte Bydler

Tsuyoshi Ozawa

Many works by the Japanese artist Tsuyoshi Ozawa (b 1965 in Tokyo) refer to the concepts and history of art. Several of them develop and change in the course of an exhibition, and eventually consist of their aggregate history. He has been involved since 1993 in the Nasubi Gallery project, a mini-gallery that fits into one of the small, white crates used to deliver milk in Japan in the 1960s and ’70s. He describes the gallery, where he has produced nearly one hundred exhibitions of works by himself and others, as “the smallest mobile gallery”. It contains everything a normal gallery has, and when he puts on an exhibition he places it in a street, sends out invitations, has an opening, and occasionally even employs the homeless of the area as gallery guards.

My knowledge about Koropokkuru (detail), 2004

© Tsuyoshi Ozawa

Photo: Naoki Takeda

Ozawa has also worked on more large-scale projects, such as the Museum of Soy Sauce Art, a humorous take on Japanese art history. In recent years, the interactive element has been further developed. His work Sodan Art Cafe, which is part of the Sodan Art series, consists of a cafe where visitors can submit their ideas on how the cafe could be changed. Out of the large number of suggestions he assesses what is possible, financially, spatially and morally, and then implements the changes in the course of the exhibition, so that the cafe takes on a new form daily. One version, Sodan Art Cafe Manga, was shown at the latest Berlin Biennial.

Another work where the audience is directly involved is the guide book Ozawa made for his own art. This colourful book in several chapters guides visitors through his artistic oeuvre. At the Venice Biennale in 2003, Ozawa participated in the Dreams and Conflicts section, showing his Capsule Hotel Project, a variety of the Tokyo hotels where people who can’t make it home in between two long work shifts can stay overnight in a little capsule. In Ozawa’s version, visitors can also lie down in the capsules, but the work has a political undertone, since it also alludes to the temporary dwellings of the homeless who live on the streets of Tokyo and other cities.

One of Ozawa’s latest projects, Vegetable Weapon (2003), consists of photographs of people holding models of weapons made of vegetables. He created the work by asking people to prepare the most common dish from the region where they live. He then assembled the ingredients to resemble weapons and photographed the people together with the weapons. This is a game with a serious underlying message about how differences in (food) culture can turn to weapons in our hands.

Magdalena Malm

Katya Sander

Katya Sander (b 1970 in Denmark) belongs to a young generation of Danish artists with a strong interest in social issues. Apart from being an artist, Sander also works as a writer and editor of the magazine Øjeblikket and other publications.

My knowledge about Koropokkuru (detalj), 2004

© Katya Sander

Photo: Naoki Takeda

Katya Sander’s works revolve around themes such as the private and public domains. She explores language, identity, urban planning and democracy. One element of her fascination with public spaces relates to the public space of the news media. In her works, the viewers, or, more specifically, the people who are affected, are involved actively. She bases her works on specific situations, and the people engaged in the situation participate in the work. Katya Sander says that she is not interested in what art is but in what art or the artist can make out of the existing possibilities. Therefore, it is only logical that her projects almost always take place outside the gallery sphere, or take their material from more everyday spaces.

A considerable part of the public domain and common ground consists of language. When it comes to belonging and identity, name-giving is a crucial component. In the project If I Give You a Name, Will You Give Me One? Sander examines name-giving in relation to spaces. She collects graffiti from public toilets in Stockholm and reproduces the names she has found there on the gallery wall. In the museum toilet we find a graffiti quote from Judith Butler’s book Excitable Speech (1997): “And what if one were to compile all the names that one has ever been called? Would that not present a quandary for identity? Would some of them cancel the effect of others? Would one find oneself fundamentally dependent upon a competing array of names to derive a sense of oneself? Would one find oneself alienated in language, finding oneself, as it were, in the names addressed from elsewhere?” The text asks how anyone or anything external, or any language, can convey a person’s identity.

The public toilet is both a public space and a very private one at the same time. The names and appellations scribbled on the walls tell us something about the person who wrote them, and the people they refer to. They form a kind of gridwork of all the people who use the toilets, and the individuals who people their imaginations. Perhaps the list of graffiti on the wall is the sum of the names, of the identities, of the people living in Stockholm?

Magdalena Malm

Fia-Stina Sandlund

Fia-Stina Sandlund’s works often analyse various forms of social oppression and inequality, sometimes developing into direct actions. The group “Unfucked Pussy” which consisted of Fia-Stina Sandlund and Joanna Rytel, attracted attention with an action against the Miss Sweden pageant, which they picketed with a banner bearing the word “gubbslem” (Old men’s slime).

Afghanistan, 2001

© Fia-Stina Sandlund

From the photoseries Images of Fall

The feminist perspective is an element in Sandlund’s democratic pathos that she expresses in a variety of ways: she succeeded, for instance, in getting a place in her home town named after her mentally handicapped brother, and had a statue of him erected there. Why should only people who are obviously successful or powerful be honoured with monuments? A feature of Swedish identity is that we are one of the world’s most egalitarian countries. But how egalitarian is Sweden really, and how does the Swedish art scene reflect values relating to gender and democracy? Contemporary art is often related to something radical that wants to challenge innate conventions and established power structures. In the work Konstnärsklubben (The Artists’ Club, 2003) Sandlund examines one of the more secretive institutions of the art world. Konstnärsklubben is a club for artists that has held monthly meetings at Konstnärshuset in Stockholm since 1856. The club is a select member forum for informal encounters, lectures and dinners for the elected members, and also awards scholarships. By tradition, only men are eligible for membership.

To create the work, Fia-Stina Sandlund called up and recorded her conversations with members of the club, asking them how it works, what they do, and why women are not allowed to be members. She gets various answers, with interesting explanations as to why it would be unsuitable to have women in the club. None of those she speaks to intend to resign from the club because it excludes women. The work poses interesting questions about how old structures are perpetuated and whether people can be considered responsible even if they only participate passively. While the work deals with the issue of equality between the sexes, it also reveals features that are common to all kinds of informal or formal societies, how they create their own rules and therefore can preserve old-fashioned values long after society in general has changed.

Magdalena Malm

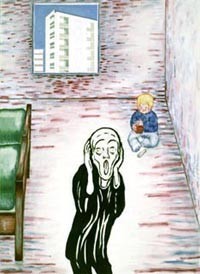

Anna Sjödahl

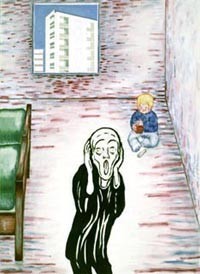

Anna Sjödahl (1934-2001) was an early pioneer for artists with a feminist agenda, an artist who insisted on the personal being political. Her art could consist of setting a table with shiny plastic plates with the characteristic 1960s industrial finish, or portraying family life in the realistic, everyday manner of the 1970s. In the late-1990s, she added scenes and themes from classic Greek mythology to her narratives. Anna Sjödahl was a sculptor and exhibited domestic suites of furniture with children’s clothes hanging out of drawers and scattered on the floor. She was also a painter and gave Edvard Munch’s The Scream a contemporary reinterpretation. In Spring in Hallonbergen (1973) the angst-ridden figure with the gaping mouth has moved to a Stockholm suburb with the usual anxieties relating to the demands and stereotypes of family life. Today, this theme has a given place among the cries of protest from the art world, where a perfectly natural phenomenon such as children does not fit in.

Springtime in Hallonbergen, 1972

© Anna Sjödahl

When Anna Sjödahl made Spring in Hallonbergen, women and everyday life were not obvious motifs in art. It may seem that art history indiscriminately links generations of artists by pointing to the influence that so-and-so has exerted. In that sense, art history resembles an archive of the artists who were the first to do a particular thing. Since there were obviously women artists even in the past, however, the historiographers ought to explain why women are so rarely included in the list of great artists. Anna Sjödahl was one of the artists who turned that around. Artistic progress is usually not about making discoveries of the kind one usually terms as “inventions”, i.e., things that benefit mankind and facilitate life for the artist and audience as a collective. It would be more correct to use the word recognition when describing ground-breaking artistic efforts. That would clarify the fact that “pioneers” are created first when their “followers” are successful.

Sjödahl’s images express a vision of equality in historiography, as in life outside the sphere of art. Equality requires that all parties have access to, and are evaluated according to, the same context (which does not mean that the yardstick is the same). Women artists must be recognised in the same forum that their male colleagues turn to for their resources. Would Munch’s Scream be as great with a crying infant sitting on the floor? Does the reverence for traditional genres and motifs help to preserve the current inequalities? Anna Sjödahl contributed to making graphic art and oil painting move over and give room for installations of ordinary furniture and materials associated with commerce and popular culture, as transient and tempting as boiled sweets.

Stig Sjölund

For decades, the discourse on art has been dominated by an analytical and objective exploration of social and symbolic structures, both contemporary and historical. With aesthetic tools we have approached and scrutinised various ideas and conventions. But until now, no one has seriously attempted to approach, and perhaps even less to scrutinise, that which is hidden on the absolutely and implacably silent and eternal other side.

Finally Some Good Assholes, 2002

© Stig Sjölund/BUS 2004

Performance i utställningen Fundamentalisms of New Order, Charlottenborg, Köpenhamn.

Courtesy Brändström & Stene

In The Scanning, however (Uppsala Konstmuseum, 2003), this is exactly what Stig Sjölund attempted to do, with the aid of spiritualist Birgitta Tholander. Few works of art have, like this amalgamation of Gesamtkunstwerk, exhibition, installation, phenomenon or happening, depending on how we choose to regard The Scanning, so distinctly sought to approach the other side, the supernatural, and our ambivalent relationship to it. Stig Sjölund is undeniably an artist, but he is one who unremittingly demonstrates what the work methods of different artists can be like. In that sense, his artistic projects are always more or less unpredictable, but they are also very precise and specific to the situation. His art resides in the wide field that usually goes under the name of relational aesthetics, a field that is not that simple to describe as a specific genre but more as a set of parallel, but not necessarily congruous, practical and theoretical explorations of the social domain.

These socially orientated explorations now seem to be approaching the extreme outer boundaries of the social domain. After Documenta XI in Kassel in 2002, curated by Okuwei Enwezor on the theme of globalisation, there no longer seems to be a corner of the world that has not been studied in detail. It is perhaps less surprising, in that light, that Stig Sjölund took the step over to the other side, where he tries to scan the supernatural, the unexplored worlds that could, paradoxically, contain the answers to all the questions we have asked in the world we already know.

The world that Stig Sjölund reveals together with Birgitta Tholander is ultimately about the rules and norms of the social domain. What is acceptable within the limits of normality? And where is the boundary between fact and fiction? Here, as in previous works, Stig pursues his examination of crucial questions about norms and values.

Rodrigo Mallea Lira

Snezana Vucetic-Bohm

Snezana Vucetic-Bohm based her early works on a tradition of feministically influenced images where the arranged photo played a crucial role, especially the fictive self-portrait as an instrument of examining and criticising primarily cultural female paradigms. In this vein, she produced Self-Portraits 1991-1994, a series of photographs where she places herself, in different guises, in authentic settings in the Balkan, Germany and Sweden, and poses questions around dual identities. Gradually, however, she has adopted a more directly documentary approach, using a more conceptual style of photography to explore the world that forms the framework of her life and history – a rather dry, descriptive work in which she shifts the perspective.

Self-Potrait, 1991-94

© Snezana Vucetic Bohm

Although the arranged photograph has been an effective device in an art historic perspective, the method also incorporated an avoidance of the personal perspective or personal relationship to the role and the setting. The analysis and criticism of how gender roles and identity are reinforced took place in various enactments, highlighting the fact that it is possible to alternate between, and reject, roles, and thus, to demonstrate that identities are not hereditary or inherent.

In Snezana Vucetic-Bohm’s work the examination of how identity is created has also been central, but her method has always been to go via her own personal sphere while maintaining a critical perspective. In the photo series Bratstvo Jedinstvo 23/Brotherhood Equality 23 (2000-3), an ongoing project, she documents an apartment block and the people who live in it. The block was built by her father and his three brothers in Montenegro, and Bratstvo Jedinstvo 23 is simply the street address. The brothers built the house primarily for themselves and their families and grandchildren, sharing a dream of being reunited and living together in one and the same place.

When Snezana Vucetic-Bohm studies the building, it is basically her own history she is examining. For years, she has been revisiting this house, together with her parents. She is interested in how the relationship to, and preconceptions of, one’s homeland form one’s construction of belonging and identity. She explores how different generations, and those who stayed behind and those who left, have different perspectives and opinions about the homeland. Another perspective focuses on the symbolic meaning of the building and its address, as monuments to the dream of the extended family.

Rodrigo Mallea Lira

Chun Lee Wang Gurt

Chun Lee Wang Gurt (b 1957) belongs to a generation of Chinese artists who have pursued a career abroad. Starting in the late 1970s, she studied in Beijing, Stockholm and New York. While most north-east Asian artists who go abroad choose to settle in France or the USA for historical reasons, Chun Lee Wang Gurt’s personal relationships took her to Stockholm via New York. She has maintained her interest in communities, social constellations, constructions or constitutions. Encounters between people are coloured by lasting visual impressions and audible traits – including dialect, physical appearance and dress – and a myriad of invisible experiences and features. All these serve as a mould that more or less permanently impresses the rules of the community and its reverse side: exclusion. Chun Lee Wang Gurt demonstrates how various communities perpetuate a model of themselves, both in the shape of historical monuments of the usual kind, and in the form of daily habits that grow into social monuments. In the exhibition I Wish You Were Here (2002) she used different languages, spatial constructions and group portraits to reveal the alternately physical and immaterial frames of community.

Reunion, 1994

© Chun Lee Wang Gurt

This field of interest also underlies the artist’s work as head of the graphic art school Grafikskolan in Stockholm (1998-2004). Heading a non-commercial cultural institution was a full-scale relational artwork. In prevailing cultures of artistic leadership and political decision-making processes she could apply resistance as a tool for building bridges between how she perceived herself and how she was received by others with regard to language, authority, change and artistic tradition. There was no back-door escape route via the relational art concept (as when artists construct a defined situation relating to the question “what happens if I do this?” and present the results to the already initiated art audience). Her intention was to devote a couple of years to realising the school’s artistic ambitions. But Chun Lee Wang Gurt stayed in the situation and took the consequences of her post as head of the school for six years.

The video and photo work To Travel (2004) can be regarded as a double group portrait that stretches out the portrayal over time. The genre of group portraiture emphasises the similarities, belonging, naturalisation and family ties of the depicted – also in a broader sense. The family album’s snapshots of weddings, funerals and children have now been joined by the video which even more convincingly conveys the feeling of closeness to people remote in time and space. But outside the environment that the group portrait was intended for – the family album, the club or the boardroom – it loses its relevance. We always need to know something about what links the depicted people. Chun Lee Wang Gurt’s suggestions of what brings them together make both the family likenesses and unlikenesses stand out.

Charlotte Bydler

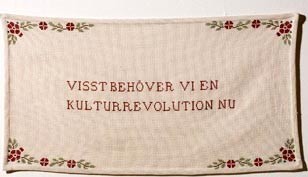

Måns Wrange

Måns Wrange’s work could be described as an intricate network of processes. It frequently consists of major socio-political studies that span several years and resemble research projects more than anything else. Looking at the choice of subjects and his method of approaching them, we get the picture of an artist with a social commitment above all. However, Måns Wrange devotes enormous attention to every separate part of his work, be it the drawn-out processing of the subjects or the spatial presentation of the works.

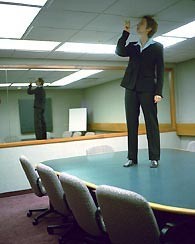

Monument Over the Average Citizen Marianne, 2001

© Måns Wrange

Schirn Kunsthalle i Frankfurt, Photo: Måns Wrange

In Ombudet – Institutet för samhällsförbättring (The Representative – Institute of Social Improvement), his most extensive mosaic of works, including Medelmedborgaren (The Average Citizen), Måns Wrange launches a challenge against aesthetic boundaries and the artist’s role. Together with the architect and designer Igor Isaksson, Måns Wrange founded this organised network of culture and research which serves as a combined exploratory think-tank and political lobby organisation, aimed at publicising and formulating proposals on how to solve various problems in society. This institute can be added to the long chain of institutional works signed Måns Wrange, that stretches from Revolution in the late 1980s, to the well-known Misslyckandets encyklopedi (Encyclopaedia of Failure) in the early 1990s, in which Måns Wrange’s alter ego Professor Severin B Johansson (who developed the encyclopaedia) erodes the boundaries for the artist as originator. One of the things revealed in this tender study of failure was the many aspiring artists who nearly succeeded in becoming “immortal” but instead disappeared into oblivion.

Although the professor himself was fictitious, the encyclopaedia promoted an operative interpretation of reality that could be applied when examining society and its structures. The Average Citizen is a work in the same vein. Måns Wrange has studied how statistical averages influence and govern our everyday lives. With help from Statistics Sweden (SCB), he deduced the statistical profile of the average Swedish citizen. The result was a 40-year-old woman who lives in a one-bedroom apartment and has an annual income of 180,000 kronor. Through a media campaign, Måns Wrange made contact with a person who matched these criteria exactly, and by interviewing this person, whose name was Marianne, put normality into perspective. As in so many of Måns Wrange’s works, this was an analysis of the means by which society is described and indirectly normalised. The Average Citizen poses questions about the relationship between mean averages and representations that can shed light on how the welfare state, in its striving for equality, through the simplifications of statistics, might contribute towards certain groups being perceived by others as deviants.

Rodrigo Mallea Lira