Esra Ersen, If you could speak Swedish..., 2001 © Esra Ersen

DVD

What next?

Let’s not forget, as we look at its ruins, that the torch of Swedish social democracy once burnt brightly, not just at home but also in the minds of progressive thinkers across the world. In the 1960s, 1970s and even early 1980s, its system was perceived as the future that could work – combining socialist compassion with individual rights, economic growth with working class solidarity. As a young socialist growing up in Thatcher’s Britain, I looked on the ‘Middle Way’ with wonder. Though coined in the 1930s, for us the phrase was still shorthand for a successful political utopia, where the unimaginable happened and the state really was on the side of the people. Even in 2001, when I moved to Sweden, the ‘national myth’ from which Gyllenhammar desired liberation was still evident in the valedictory comments of my Scottish friends: ‘you’re lucky to be going where society still exists’ being the gist of their understanding. Knowing Sweden a little bit even then, I was slightly taken aback. ‘You still believe that’s true’, I said, and they replied that yes, they did, but they ‘hadn’t thought much about it recently, to be honest.’ That ‘our national myth’ persists in relatively affluent and informed Scotland might also be an indication of how Sweden continues globally to be a beacon of social welfare and personal freedom to thousands of emigrants looking for a place under the Western sun.

After three years of living in 21st century Sweden, I have had a chance to see how that Swedish Model holds up internally. It seems to me that on one level, the Model was an extraordinarily successful international marketing campaign. If failing post-industrial cities tried to re-brand themselves in the 1990s as cultural capitals, then Sweden had done a similar exercise in the 1930s, thanks in part to Marquis Childs’ US publication of Sweden: The Middle Way and in part to a desperate European desire to have one national state where the basic principles of socialism led to apparent social cohesion and economic growth. Certainly, the appearance of the ‘Middle Way’ once had a substantial basis in reality, with an identifiably different political and economic programme. If we are to rethink the Swedish Model in any optimistic sense, we have to begin by acknowledging the real and significant achievements of Swedish society before the late 1980s. Indeed, they are one of the compelling reasons for living here – still. It is only that my experience of those days has been largely through the nostalgic memories of disaffected social democratic friends, or a hard critical appraisal of the ‘strong society’ and its ultimate failure. Aside from those reactions, it has been sadly, though perhaps inevitably, difficult to find a political discourse here that differs markedly from any globally integrated nation state.

Yet internationally, Sweden’s reputation has largely survived the planetary changes that first weakened its integrity and then fully normalised its society to the capitalist mainstream. Now, through a complicated course partly charted by the hopes of new migrants and succoured by a popular blind faith in the immortality of the ‘national myth’, the survival of that older reputation feeds back into what remains of Sweden’s sense of its national exceptionalism. It is a comforting phenomenon for both politicians and voters, but increasingly it denies the evidence in front of our eyes and makes it all the harder to imagine what may lie beyond or to the side of globalisation the neo-conservative way. This same sense of a political discourse suspended by its own past struck me most recently when thinking about the reaction to Anna Lindh’s murder. In many ways it was understandably just as traumatic for Swedes and the world as Olof Palme’s death nearly 20 years earlier. For a moment, to an outsider like me, it felt like nothing had changed in the period between – Sweden’s uniquely consensual, ‘open society’ was once again under threat but any real change to social behaviour would be resisted once again. I agreed, I sympathised, and yet, and yet . I can’t help thinking that there are real differences. Lindh was killed when she was campaigning not for Sweden’s uniqueness but for full integration into the European economic system. She died by the inexplicable act of an immigrant to Sweden, a group in this society that are usually considered only in terms of integration and not as a challenge to the culture of social democracy and its history of consensus.

To try to explain my understanding of this state, I have to resort to metaphor. Let us imagine for a moment that what happened in the late 1980s was not a relatively simple political change but something much more psychologically profound. Let us say that what we are living through now is akin to the condition of a society and culture following an earthquake. The social democratic Sweden that forged the myth we speak of, was built high and shining on the back of a compromise between the extremes of an untrammelled free market and a repressive communist dictatorship. The end of European communism heralded the first tremors of the earthquake and the end of any possible ‘middle way’ politics. The floodtide of free market fundamentalism that followed in its wake undermined the most of the structures that had already been built. Today, 15 years on, many of the edifices that made up the social landscape of social democracy are still erect, though there is an unspoken expectation that they too may crumble. In fact, the props and scaffolding keeping them standing are some of the most reassuring new features we see. But more than changes on the surface, it appears that fault lines have opened up below ground level. These fault lines were never expected by the prophets of the catastrophe, and the new canyons and rivers they have created stretch far beyond Sweden’s national borders. These fault lines also serve as highways connecting places that were never previously related. Along them appear figures, groups of individuals who gather under convenient flags labelled ‘refugee’, ‘migrant’ and ‘asylum seeker’. These figures, whose arrival is a consequence of the earthquake but not its product, have no inherent knowledge of the history of social democracy, though they might share some notion of the ‘national myth’. If they seem ready to repair the buildings or shape a new landscape, it is unlikely to bear much relation to the old familiar one. The awkward choice for those with the memory of the old system and the consequent sense of loss is: ‘Do we work with them, however inadequate the results may be?

We can choose to call this metaphorical earthquake by different names: globalisation, ‘the post-political consensus’, or multiculturalism depending on whether we emphasise the change to economics, politics or culture. For, though ultimately connected, the distinctions between these three are very significant to understanding what and how we can think beyond the current situation. The first psychological consequence of any earthquake is trauma, a reaction that lasts long enough to overcome the horror of everything that has happened. We saw that vividly during the nineties in the bewildered looks of trade unionists, politicians and old social democrats as well as through the cynical adjustments made by the ‘early adopters’ to the new situation such as Gyllenhammar. Today, Swedish and European social democracy could be seen as post-traumatic, suffering from stress syndrome in some areas, but starting to ask the simple question – ‘what next?’ The answer to that question depends in part on your approach.

Let’s stick to our economic, political and cultural subdivisions. From an economic and political point of view, there might be the beginning of attempts to imagine internationalised labour movements and political action. The World Social Forum and other supra-national attempts at creating a political discourse that sees through the fog thrown up by global free market democracy. But the journey from imagination to the reality of global self-government seems longer than the lifetime of this generation. In cultural terms, the shock of the 1990s to a society as successfully integrated and socially (and ethnically) coherent as Sweden has been exaggeratedly severe. Because the shockwaves opened up fault lines that were not previously visible, it undermined some of the most basic ground rules of the ‘strong society’. Where the force of consensus had assumed that the role of culture was settled across society, now it comes under searching inspection. Where culture and specifically visual art had always held a simple functional role in social democratic thinking, it now becomes a battleground for competing understandings of the representation, power and tradition. Where art without a clear social function was seen as outside the terms of the political system and therefore marginalised as decadent and weak, it now becomes, I would argue, one of the tools to view the consequences of the great changes we have experienced and start to propose alternatives.

So, while the symptoms of destabilisation are visible across Europe in different ways, it is in Sweden that some of the most deeply held cultural values of the political system are stretched to the limit. Precisely because of the continuation of the ‘national myth’, the challenge of the earthquake is greater than almost anywhere in the Western capitalist world. That challenge is to the reasons that Sweden is ‘Sweden’ in the eyes of itself and the world. It is a shift in the basic conditions that allowed social democracy to work its magic wand of socially contracted peace and prosperity. And this challenge is made in cultural terms, not only because of ethnic difference but also in the private and public conceptions of how and why a society and its individuals work, spend, pray and consume their leisure.

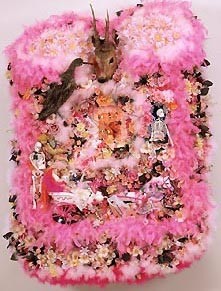

Is there any room for optimism in this picture of post-traumatic adjustment? I believe there is, but it is only at the small-scale and intimate level of cultural exchange. I can see changes at the micro level of artist-run organisations and artistic projects working in the flux of social change that point the way more firmly towards a post-post-earthquake condition – one that understands and embraces the new landscape and could not survive without it. Though the kind of exchanges that some contemporary art projects knowingly cultivate are long-term in terms of any social efficacy, they can be seen and made real today, albeit for few people and for a limited period of time, rather than postponed to an eternally delayed ‘utopia’.

To propose that small, local and independent cultural initiatives are a part of the way beyond simple adjustment to the earthquake might seem absurd, or at least privileging an activity that is powerless in the face of such dramatic shifts in the dominant system of values, but that is (arguably) their very condition of possibility. Many of the initiatives I am thinking about, which happen across the world in different guises, have sought ways to question current conditions, avoiding the overt oppositional critique of the anti-globalist protestors and refusing to rely solely on the power of individual self-expression in the tradition of classical art. Instead, their projects work through discussion, dialogue and a tangible ‘play’ with the very mechanisms of globalisation. The groups are engaged with their locality and with individual social actors within them, and in doing so they naturally propose changes in social and economic relations through art. This intimacy with a particular environment acts as an antidote to the utopian tendency in art today. Utopias are dangerous in many ways, not only if they are made real but even as a proposal, when they seem too often to lead to a kind of lazy disinvestment in the existing situation. Contrarily, there is always a danger of romanticising the local in which only indigenous protagonists can act with legitimacy in the immediate environment. This tendency can be tempered by a global exchange between different localities that acknowledge pluralism and promotes reflexive criticism.

To be a little more specific, let me use my home base in Malmö as an example. The political situation is rather static; a long-standing social democratic administration seems to want to avoid the hardest questions of social change. Recently the ‘strong man’ of the city council has demanded a halt to all economic migration of non-Swedes and yet up to 25% of the population (depending on how we are counted) is already connected to another culture. Economically, the old warhorses of the Malmö economy, shipbuilding and engineering, have almost disappeared, ironically leaving the promise of a Danish-led foreign investment boom as the main source of hope. Yet in terms of visual culture, Malmö has rarely been more interesting. A combination of institutions ranging from the art academy to Signal artists’-run space and including Rooseum, Konsthallen and Konstmuseet support not only a series of international projects but genuine ‘grassroots’ activity that springs from the very questions of migration, industrial collapse and social democratic inertia that define politics and economics. Artists such as Luca Frei, Runo Lagomarsino, Maria Bustnes, Ylva Westerlund and Per Hasselberg are all working on Malmö and the specifics of it in one way or another. Their projects include an investigation of the plans of a new city hall (Hasselberg), the street market culture (Bustnes) or the anti-EU riots (Lagomarsino) and are all local and global in their focus, drawing as they do on the ‘local globalisation’ evident on the streets of Möllevången or Rosengård. In contrast, a Frei uses his (outsider) understanding to take certain social democratic educational theories to a school in Latvia and Westerlund looks more abstractly at the very processes of consensus negotiation themselves. In Rooseum, we have been running a programme called In 2052 Malmö will no longer be Swedish that aims to raise the issues of ethnic and national identity and the problematics of integration policy by inviting artists from outside the city to spend up to six months working with communities and individuals in Malmö. Artists have, for instance, developed comparative studies of the migration of continents, birds and people (Lyn Löwenstein) or looked in detail at the city propaganda publications and compared it with her individual experience of Malmö (Esra Ersen). Such projects often pose more questions than answers, but they look at Sweden following its earthquake moment with eyes that do not judge so much as try to find a path through and along the fault lines that have seemed so threatening.

It is important to take advantage of this moment to emphasise not only that ‘foreigners’ are making art in Sweden but also that Sweden itself is being changed by that activity. In small, uncountable and often gentle ways, the old truths of ethnic homogeneity leading to social consensus are breaking down. A stark choice may face us in the future: either to let go of the ‘national myth’ and join not only Europe but every citizen of the world – and to understand how damaging that may be to tradition, custom and identity; or to close up and defend the existing state as it is against all forms of globalism. Neither future is very comfortable for old school progressive politics it seems. Rather it is in the cultural field, and visual culture above all, that we, as a society, can start to see the outlines of a way of living together as individual citizens bound by no more than our own self-adopted sense of belonging.

Text from the catalogue by: Charles Esche