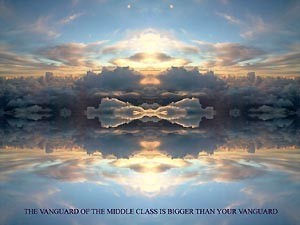

Carlos Capelán, The Vanguard of the Middle Class is Bigger Than Your Vanguard, 2004 © Carlos Capelán

We Swedes

We often hear of “our immigrants”, that is, a sort of property that “We Swedes” have to do something about: an “us” and “them” situation. In this essay, I will look at different ways of seeing or not seeing the Other. From this perspective I will also look at Swedishness, and how immigrants attempt to approach Swedish culture.

The eternal dichotomy of the Self vs the Other

The identity issue always comprises a subject and an object who interact: the Self, and the surrounding, the Other. Both are subject and object. The Self defines itself in relation to the surrounding, while defining the surrounding. The surrounding, in its turn, as a collective subject, defines itself and the individual, the Self. But how does this take place? Against what background do they define one another?

In his book The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other, the Bulgarian semiotician Tzvetan Todorov analyses two ways of “not” seeing the Other, through Christopher Columbus on the one hand, and Hernán Cortés and Bartolomé de las Casas on the other. The first is based on the evaluation of the Other as an equal or inferior to the Self. The second is based on the distance the Self creates to the Other, where the Self copies the values of the Other and identifies with them, or assimilates the Other and forces it to accept the Self’s values. Between these two alternatives (subjugation of the Other or subordination to the Other) there is a third way, according to Todorov: neutrality, or indifference. This entails not being familiar with the identity of the Other. In that scenario, the Other does not really exist in the universe of the Self, while the two former alternatives involve the Self discovering the Other, as Todorov describes it in his introduction.

Columbus did not regard the inhabitants of America as a culture with its own structure, a culture that he should perhaps get to know. On the contrary, he was fairly certain he had come to Cipango (Japan), an island that Marco Polo had described. Nothing in America fitted the description, but he insisted on “adapting” what he saw to his preconceptions of the country. Columbus really only had one thing in mind: to conquer the territory he set foot on, and to take their riches (in the name of the King and Queen).

Unlike Columbus, Cortés tried to get to know the Other, not because he was interested in a cultural exchange, but as a strategy to conquer the Other and force it to adopt his values. He had an affair with an Indian woman, Malinche, who was his interpreter and helped him to understand the Aztec way of thinking. Las Casas, on the other hand, considered the Indians as equals, to the extent that he forgot to see them as the Other, rather than a reflection of himself.

The intentions of Columbus and Cortés were the same. Both wanted to defeat and conquer the Other in the quest for riches and to win the honour among their peers in their own culture that they believed they deserved, according to their own cultural code.

One would think, or wish, that there were a “fairer” way of encountering the Other. Todorov proposes a way, namely to regard the Other as simply another, without trying to assimilate it to one’s own values and without assimilating one’s own values to the Other.

In our contemporary, globalised, world, the relationship to the Other works according to Cortés’s principle: assimilation of the Other into the dominant culture. In other words, if I don’t speak the language of the dominant culture, I don’t exist.

Swedishness

For many decades, Sweden lived in a fairytale world of ethnic and cultural purity. Everyone was thoroughly Swedish: protestant, blonde, blue-eyed, honest, kind to one another (and to the whole world), wore the same clothes, and, obviously, spoke the same language, even if the “same” language was pronounced differently in different parts of the country. The Swedish national costume in the colours of the flag was created, and all summer cottages were painted the same red colour. People looked like each other, and yet different, because they were all as free as their neighbours, and all Sweden’s neighbours. People could go for walks in the middle of the night without feeling threatened, this was an “open society”. until Prime Minister Olof Palme was murdered in the street in Stockholm in 1986, and until Foreign Minister Anna Lindh was murdered in a department store in central Stockholm in 2003.

In the installation Swedish Metall and Borgen (The Fortress) the artist Peter Johansson deals with this bubble which people would have preferred to go on living in, and holds a mirror to Swedish contemporary society. A self-centred person hums in his little fortress without noticing that it is on fire. A bit to the side there is a table made of genuine Swedish steel, the same steel that is used to make weapons that kill people somewhere else in the world. On the table are several tourist bags in the colours of the flag with “Sweden” written on them, each containing a hammer made of plush velvet, also in the flag colours, that strikes the table.

In his work, Johansson criticises and ridicules “Swedishness”, using the stereotype images that Swedish culture has created of itself. He paints his body like a traditional wooden Dalarna horse (he comes from Dalarna), he slices Dala horses and packages them like meat, he dances typical folk dances in typical costumes, he builds a sauna and invites the audience to use it for real, like people do at home or in the saunas found all over Sweden.

What is Swedish? Who decides what is Swedish, and what makes people feel it belongs to them? And why (and when) do people strive to demonstrate their “uniqueness”? When an association was formed in 1904 to promote the Swedish national costume, the aim was to resist influences from other countries and other people, and to protect something they considered to be “theirs”. In addition to existing costumes, a new one in the colours of the flag was created. The flag is an important symbol for nationalist feelings (the Self) against foreign groups (the Other). The national costume was a kind of defence against foreign impulses that could compete with what was seen as uniquely Swedish, which, bizarrely, was specially created for the purpose. The most Swedish tradition of all, Midsummer, has many central elements that are, in fact, “foreign”: the Midsummer pole is a German import, Swedish new potatoes were not introduced until the 1800s and came originally from Chiloé, southern Chile. The same goes for strawberries, which have to be Swedish-grown and freshly picked for the festival – they are a cross between wild strawberries from North and South America created by the English. No one knows the exact origin of the Midsummer tradition, which is not entirely unique, since it coincides with St. John’s Day, celebrated in many places in the world, albeit with a different content.

Every culture has its own traditions that often resemble those of other cultures, but it is the specific content that a certain culture invests in the various elements that makes them unique. Traditions have a long history, a history of adaptation to new contexts, new interpretations and new people, an endless chain of “foreign” phenomena that are integrated.

Culture from a cultural-semiotic perspective

Cultural semiotics define culture as “a system of relationships between people and the world”, which, on the one hand, regulates people’s behaviour, while, on the other hand, determining how people see and represent the world. The world is an information flow that culture can either interpret, or not. If the information is interpreted, it will be classified in a special way according to the internal structure of the culture. The interpreted information is then incorporated with the culture, forming a new manifestation, a text. This means that every culture has its own way of accumulating information and producing cultural manifestations.

Going back to Midsummer as a unique text to Swedish culture, we see that each separate element can be found almost everywhere in the world. But in this particular case the elements have been interpreted in the way that shapes this particular tradition.

The eternally foreign

One of the interpretation processes that have been taking place in Swedish culture over the past few decades concerns the “new members” of society, the “immigrants”. These, in many respects foreign, elements in Swedish culture are catalogued and placed in different compartments. The prevailing criterion for the cataloguing has been their distance to the “purely” Swedish, based on the origins of their ancestors, which is usually revealed in their surname. Physical similarities or country of birth is usually irrelevant. You may be born in Sweden, be blond and blue-eyed, but if your name happens to be Juana Pérez or Mohamed Fares you are a foreigner all the same. The categories are: immigrants (born abroad, therefore at a greater distance from pure Swedishness); second generation immigrants (born in Sweden but with parents from another country); immigrants with one parent born abroad, immigrants with a foreign background (those with a whiff of un-Swedishness in their blood). In addition, there are cultural differences. There are continents that Swedish culture feels “closer” to. This feeling of “closeness” relates largely to religion. Cultures with a Protestant background feel the closest: Germany, the USA, Britain. These are followed by other Christian countries, Catholic countries, including many European countries and all of South America that constitute the “Latino culture”. At the furthest end of the spectrum is the Moslem culture, which not only has a different god and different religious traditions – but many of the women demonstrate their faith by wearing special clothes that feel out of place in Swedish culture.

Unfortunately, this categorisation has not resolved the much-debated problem of integration, but has merely defined the differences. This permeates Swedish society, not to mention the art scene. It is not easy to find an artist with an “immigrant background” – of any kind – in the activities of the major museums. They are barely even regarded as real artists in the Swedish art world. The prefix “immigrant” denotes non-belonging and has such a negative ring that you would prefer not to be in a situation where the prefix attracts attention, or where there are other immigrants – because then you risk not being taken seriously ever again.

Strategies of adaptation

As argued earlier in this essay, the identity issue involves a subject and an object, who change places depending on who is defining whom or what. If we now put immigrants in the place of the subject, and make Swedish culture the object, we can observe various ways of seeing The Other. Here the process is double: on the one hand, the Other is interpreted according to the Self’s own cultural structure, and on the other, the Self tries to work out how it is being interpreted by the Other. Consciously or unconsciously, one applies these interpretations to try to fit into the Swedish culture:

1. Living up to stereotypes. The interpretation of the Other remains on the most superficial level, that is, simplistic images of yourself or the other. If you come from Latin America, you are loud, a little chaotic, extroverted, but also a bit mysterious. You paint pictures of Indians with feathers and tell stories about the spirits of the Andes. If you’re lucky, you speak Aimara or Quechua, which makes you even more “authentic” and “non-Swedish”. You might gain some space, but you will be seen as ethnic and exotic, rather than as an artist, and even less as one among other Swedish artists. You pose no threat to the establishment, you simply don’t exist on the Swedish art scene.

2. Going Swedish. The opposite of living up to stereotypes is to “go Swedish”. You identify as much as you can with Swedish culture and its values: you become a Swedish citizen, join various (Swedish) organisations, socialise with the “right” crowd, perhaps even change your name, etc. You might even stop speaking your native language at home, to enhance the feeling of integration.

In both cases, the Self subordinates itself to the Other as being better, superior. The folkloristic identity denies its own identity and tries to satisfy the Other’s picture of him/her. The Swedified identity tries to adapt to the Other’s values and erase its own.

3. Approaching European culture. One road that was seen as a way of avoiding the classification of immigrant was to find links between the subject (immigrant) and European culture. Some Latin American groups feel closer to certain countries in southern Europe (especially Italy, France and Spain) than to Latin America (a mixture of different ethnic groups) and even less to the Indians. The strategy is based on finding similarities with Swedish culture via a common denominator: Europe. Alas, Swedish culture does not identify with south European countries, which belong to the “Latino culture”, just like Latin America.

4. The “Swedish” route. This mainly means going to a Swedish art school, and then pursuing the usual route of all artists. This is perhaps possible for young artists whose distance to Swedish culture is not considered as great as for artists who came to Sweden as adults.

One of the extremely few artists with Latin American roots who has managed to establish himself in Swedish cultural life is Gustavo Aguerre (born 1953 in Argentina), who, together with the Swedish artist Ingrid Falk, makes up the group FA+. Besides Aguerre’s own enormous capacity, his collaboration with Falk appears to diminish his distance to Swedish culture. FA+ have created major projects in Sweden and abroad.

5. The international route. Participation in international exhibitions is always important to an artist’s career. It usually generates respect among equals (from different cultures) and recognition within one’s own culture. Normally, an artist becomes famous in the home country first, before embarking on an international career. For some artists with an “immigrant background” the order is reversed: Abroad and then at home.

The first to succeed that way was Carlos Capelán, perhaps Sweden’s most famous “immigrant artist”. Capelán was born in Uruguay in 1948, came to Sweden as a refugee from Chile in 1973, lived in Costa Rica in 1996-1999 and has since then been living in Santiago de Compostela in Spain. The incident with the gallerist who recommended him to Swedify his name in order to fit in better with the Swedish environment is well-known. Kalle sounded better, and Capelan (without the accent) could pass, since it is similar to a well-known surname: Carpelan. Capelán, who had moved from Lund to Stockholm in 1983 in the hope of having better opportunities to exhibit his work, returned brow-beaten to Lund. In order to win recognition in Sweden and get rid of the “immigrant artist” label that people had insistently stuck on him, he had to have a successful international career. He embarked on it two decades ago, with the first Biennial in Havana (1984). Since then, he has produced and exhibited at an accelerating pace in various countries – including Sweden. He has also had a professorship in art at the Academy of Art in Bergen, Norway, and lectures at various art schools.

Over the past decade, Juan Castillo has also worked successfully on building a sturdy international platform for himself. Castillo was born in Chile in 1952 and has lived in Sweden since 1987. In the mid-1970s, he was considered one of the most interesting young artists in Chile. Beside his individual career, he was a member of the experimental group C.A.D.A. in the early 1980s. Its members, representing various disciplines, are now established artists and writers in Chile and famous throughout Latin America and other countries.

Hopefully, the “immigrant” concept will lose its importance among the younger generation, who will be more integrated and accepted in Sweden.

Immigrants in the age of globalisation

Globalisation has created a feeling of internationalisation and community in many senses, not least within art. With the progress of transportation, we can now move from one part of the world to another more efficiently and cheaper than 20 years ago. This gives artists more freedom to create new contacts with artists from other parts of the world, and even to work and exhibit in other countries. More and more exhibitions focusing on “internationalism” are organised everywhere in the world. Globalisation is not a democratic movement, however, but simply an expression of the latest hegemony. It is not Mali, Cambodia or Haiti that set the guidelines for avant-garde art, and that is not where the most “important” exhibitions are held. Nor is Bambara, Khmer or Creole the “official” language of globalisation. Artists from these countries are welcome to take part in the debate, by listening and learning.

In the age of globalisation there is a big difference between being an “international artist” and an “immigrant artist”. The former infers that the artist has gone beyond the national borders to reach out to other countries, the latter means that the artist has not managed to get inside the national borders. As long as these borders remain, the expression “We Swedes” will not include everyone who lives within the Swedish borders.

Perhaps the time has come to start seeing The Other as simply another/a different Self with whom we can be friends, co-operate and build a better Sweden for everyone.

Text from the catalogue by: Ximena Narea