Installation view ”Giacometti – Face to Face”, Moderna Museet, 2020. Photo: Åsa Lundén / Moderna Museet © Estate of Alberto Giacometti / Bildupphovsrätt 2020

About the exhibition Giacometti – Face to Face

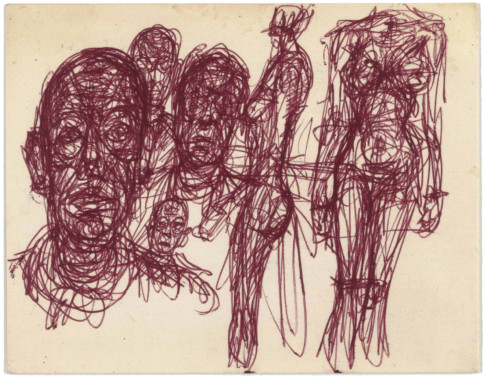

Heads

Alberto Giacometti produced his first artworks in his father’s studio in his hometown Stampa, Switzerland. He depicted people throughout his career, at times rendered from life, at times from memory – yet, from the very start, he struggled to concentrate on more than one aspect of the model at once. Finding it impossible to capture a body in its entirety he tried to delimit the problem by focussing on portraying only heads for periods of time. Giacometti claimed that ‘if you have a head, you have all the rest; if you don’t have the head, you have nothing’.

The heads went from realistic depictions, over cubism and abstraction, to violent expression. In ”Head of the Father (Flat I)” (1927–30) he carved the facial features into the plaster, as if he was drawing rather than sculpting. Giacometti kept ”Head of Diego, Child” (1914–15), a work from his youth with his brother as motif, in his studio throughout his life. Perhaps it served as a reminder of the fact that his aim has always been the same: to reach beyond what you think you know and instead depict the human form in the way it really appears to the eye.

Style: Inspiration from Other Cultures

Around the mid-1920s Giacometti looked for new ways to portray reality. A sculptor like Constantin Brâncuși would have given him the impulse to explore a symbolic and more formal aesthetic. His interest in new styles had him gathering inspiration from non-European art, like many other artists of his time. Influences from the African continent were all the rage and jazz had come to Paris. At the Louvre and the Ethnographic Museum of Trocadéro, Giacometti saw objects from the Oceanic, Mexican and Egyptian cultures, leaving palpable traces on the totem-like ”The Couple” (1926) and, a bit later, ”Invisible Object” (1934–35). Increasingly, his work was stripped of details. Cavities, soft indentations, and protruding forms hinted at bodies, although the sculptures were flat. When the artist André Masson saw these flat works in 1929, he decided to introduce Giacometti into Surrealist circles.

Disagreeable Objects: Giacometti and Bataille

Giacometti became acquainted with the writers Michel Leiris and Georges Bataille, who had distanced themselves from the Surrealist group. Bataille and Leiris were co-founding editors of the journal ”Documents”, which published material ranging from articles on film, ethnography and avantgarde art to images of fetishes and brutal scenes from abattoirs. ”Documents” became a recurring source of inspiration for Giacometti.

”Point to the Eye” (1930–31) and the erotically charged ”Suspended Ball” (1931) were quite obviously influenced by Bataille’s ”Story of the Eye” (1928), the pornographic novel filled with sadomasochism and obsession, in which round forms – eyes, breasts, testicles, eggs – play a central role. Giacometti’s sculptures from the time are often horizontal and marked by sexuality and violence. They reveal a complex relationship with women, which is also characteristic of Surrealism as a whole. Horizontality represents the bestial and low, while verticality emphasises the connection between heaven and earth. Sexuality as a human driving force is a recurring theme in Giacometti’s work, but is especially pronounced in the early 1930s.

Back to Figuration

Giacometti’s father died in 1932, and the artist mourned him deeply. Surrealism seemed to be a dead end and after a disagreement with its leader André Breton, he was expelled from the Surrealist group in 1935. From the mid-1930s onwards, Giacometti returned to the depiction of the human figure and his problems were still the same: the more he observed his model, the more the experience of what he saw changed. Sculpting something to scale was only true if he stood right next to the model. After catching sight of his friend Isabel Nicholas (later Rawsthorne) from a distance and experiencing how small she seemed, he started making his sculptures smaller and smaller. The smallest was only a few centimetres tall.

When the Second World War broke out, Giacometti initially remained in Paris, as did the playwright Samuel Beckett, whom he had met a few years before. Not until a year after the German invasion of France, he travelled home to Switzerland, where he stayed for the rest of the war. When he eventually returned to Paris in September 1945, he brought with him a number of drawings and small-scale sculptures, most of them created from memory.

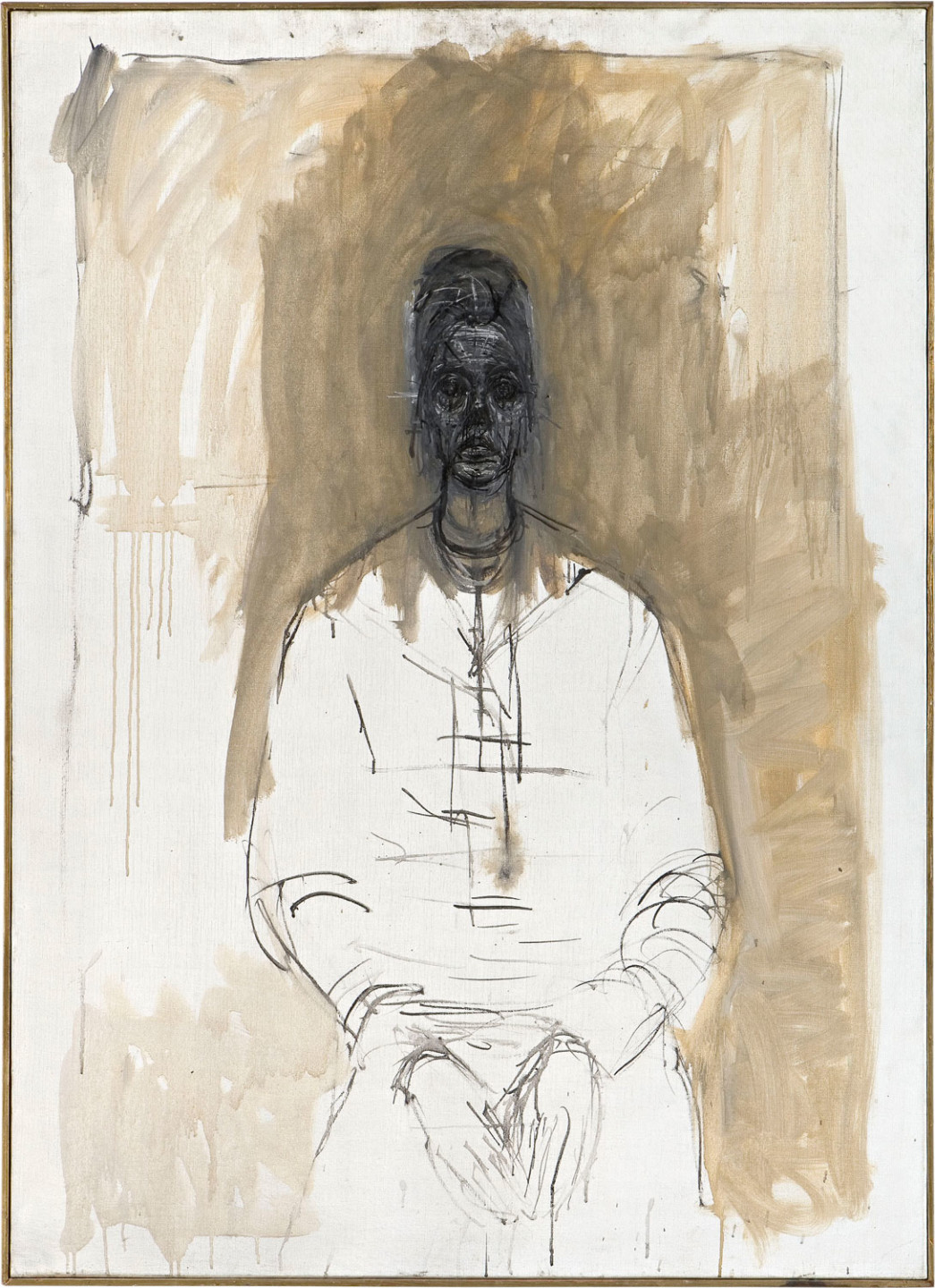

Tall Figures

After 1945, Giacometti felt that he saw reality with new eyes. His figures once again became large in format, characteristically slender with large, heavy feet. Art critics would later associate them to the emaciated captives of the concentration camps, a connection never pointed out by Giacometti himself. Although the figures are worn and haggard, they radiate rectitude and dignity and take up a surprisingly large amount of space.

Giacometti often visited the bordellos of Paris and many of the female figures are based on his recollections of prostitutes. The most prominent hang-out, Le Sphinx, was also popular among intellectuals such as Samuel Beckett, Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre. The large plinth in ”Four Women on a Base” (1950) represents the ball room floor of Le Sphinx, an insurmountable distance that had to be covered in order to reach the women on the other side. As a rule, he portrayed women standing, while the men are caught in mid-movement. He thought that it was connected to women seeming more remote to him.

The Studio: Giacometti and Genet

The humble studio on rue Hippolyte Maindron in Montparnasse was Giacometti’s workplace and residence from 1926 until his death. The walls served as a sketchpad and the room was covered in grey dust from plaster and clay. His brother Diego lived next to the studio and functioned as his assistant and model.

The French writer Jean Genet shared Giacometti’s interest in marginalised existences and lonely people. In his book ”The Studio of Giacometti” he reflects on the importance of the studio, women and death in Giacometti’s work. He found the portraits so full of life that they almost seemed petrified, dead: ‘From a twenty-metre distance, every portrait is a little mass of life – as hard as a pebble and stuffed like an egg – which could easily feed a hundred new portraits.’ For Genet, Giacometti’s figures defy time and space in their monumental loneliness. The carved and painted sculptures from the 1950s, when Genet often visited the studio, give the impression of archaeological finds.

A Double of Reality: Giacometti and Beckett

Giacometti got to know the Irish writer Samuel Beckett around 1937 and they accompanied one another for many years in Paris. Beckett was harsh and laconic, Giacometti extrovert and talkative, yet they enjoyed each other’s company. They both sought to achieve a concentrated humanity in their work, and the way there went through extreme reduction. Isolation, exile and emptiness are central themes in their respective work. In Beckett’s absurdist plays, silence is as important as the words. Giacometti’s work ”Composition with Three Figures and a Head (the Square)” (1950) resembles a stage on which no interaction occurs between the figures. The emptiness is also significant in paintings such as ”Dark Landscape (Stampa)” (1952). In 1961, Giacometti created the sparse stage design – a lonely, scraggy tree in plaster – for a performance of Beckett’s play ”Waiting for Godot” (1952).

Portraits and Failures

‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ Beckett’s words could be a summary of Giacometti’s practice. In his book ”A Giacometti Portrait” (1965), the art critic James Lord described his experience of being a model. Every day started off hopeful but ended with Giacometti painting over what he had hitherto accomplished. Just making superficial changes was unthinkable to him, since a painting or a sculpture had to be built from the inside out. As he noted, ‘I do not know whether I work in order to make something or in order to know why I cannot make what I would like to make.’

From around 1950, Giacometti spent about as much time sculpting as painting. His principal models were his brother Diego and his wife Annette. Every time he depicted them he tried to see their familiar features anew, in order to portray them not as personalities but as humans. In the 1960s he also painted a succession of vibrant portraits of his mistress Caroline, with rare strains of colour.

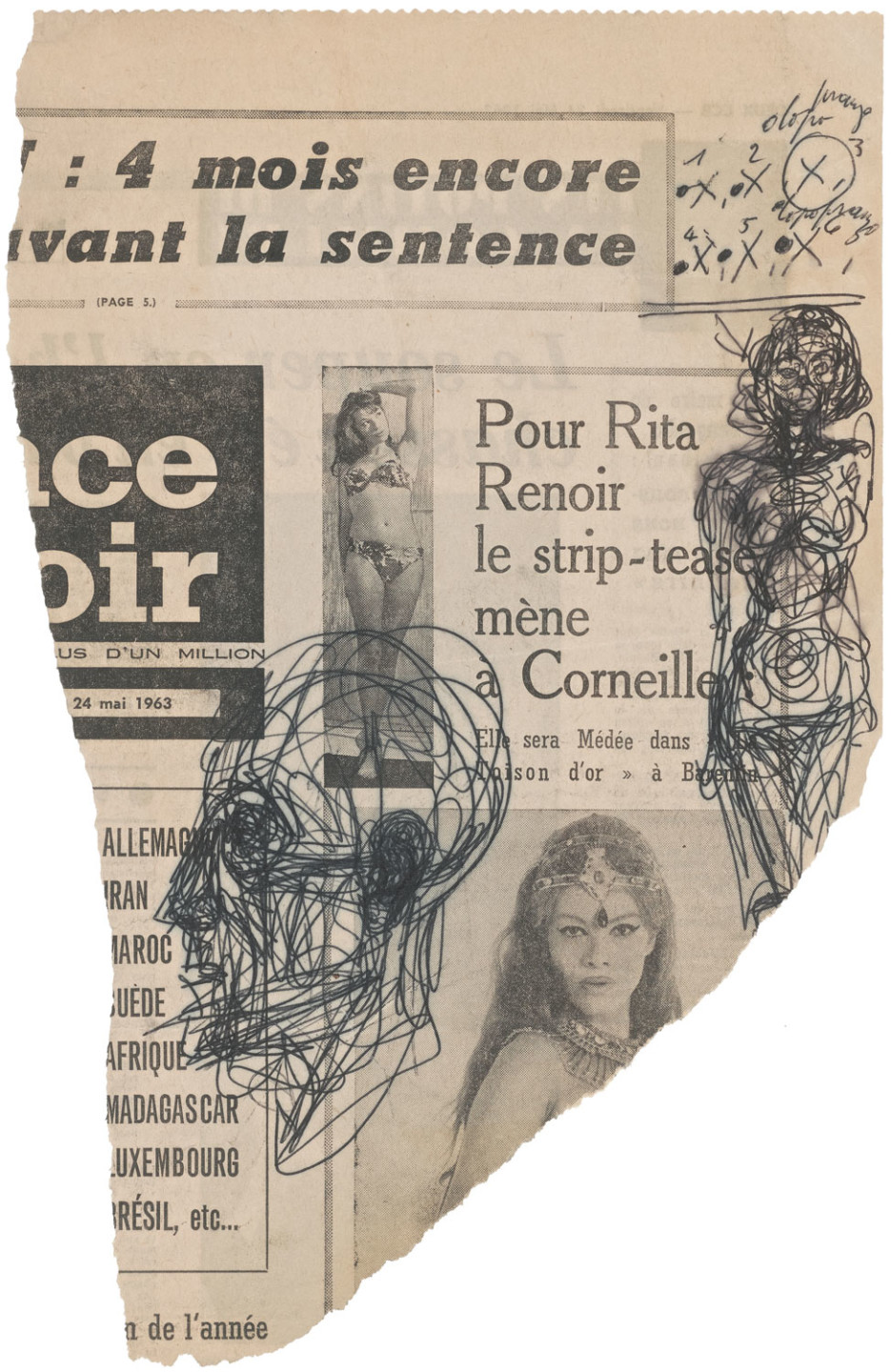

Giacometti and Paris

The neighbourhood around the studio was Giacometti’s habitat. Montparnasse teemed with life and the cafés were important meeting places for intellectuals from all over the world. He socialised with many of his time’s most prominent artists, writers and philosophers and liked to engage in discussions on politics, anti-colonialism and existentialism. Most of the time, however, Giacometti was in his studio, where art dealers and friends would visit him from time to time. Even after he had made a name for himself in the 1940s, visitors were always welcome. He would interrupt his work with a simple lunch at a nearby café. At the table he’d draw with a ballpoint pen in newspapers, copy an image that caught his interest or sketch something in his surroundings, constantly trying to capture the motif as it really appeared to him. As he pointed out himself, ‘it’s rather abnormal to spend one’s time, instead of living, trying to copy a head’.