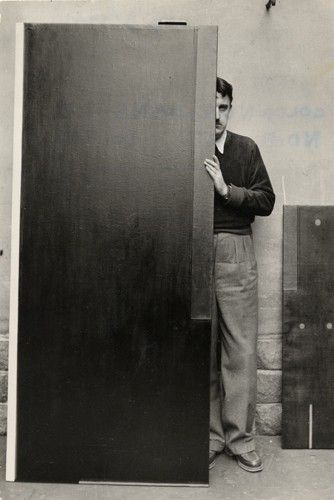

Olle Bærtling, 1950's. Photo: Okänd

John Peter Nilsson about Olle Bærtling

“He, along with Andy Warhol, was the first artist I discovered in the seventies. I was studying art history at Lund University, and Oscar Reuterswärd was the honorary professor there. He had a lot of anecdotes about Bærtling. Later on, the first exhibition I curated, at Skånska konstmuseum / Pictura, in 1979 was a tribute to Olle Bærtling.”

Many people feel ambiguous about Bærtling’s paintings. They are unlike anything else from the same period. His closest Swedish “relative” is Otto G Carlsund (1897–1948), who also had a hard time winning the approval of the art world. How should we understand Olle Bærtling’s art?

“You don’t need to understand it. There is a dynamic in it that exists only there. We should feel a surge of energy when we look at his paintings. The key trait of Olle Bærtling’s paintings is colour. They are like pleasurable yet painful dissonances.”

“He didn’t want his paintings to have any similitude with nature. That was one of his guiding principles. He sought nuances of non-nature. Take, for instance his own colour: Bærtling White – a kind of green-turquoise-white. He also had a special wash technique. Many thin layers of paint to achieve that special vibrancy.”

In the catalogue for the exhibition, the Norwegian author Øystein Ustvedt writes that Olle Bærtling’s pictures “express a modern, urban-based, life experience”. What does he mean?

There is a tradition in European constructivism where abstract art goes hand in hand with urbanisation. In the fifties, they started planning Sergels Torg plaza. Olle Bærtling was involved in that, together with the architect David Helldén. During his travels in the USA, Bærtling was also deeply inspired by the prevailing optimism there. He was swept away by it.

In many ways, you could say he was a child of his time and a proponent of modern ideas and the modern city. And he had magnificent plans! For instance, he wanted to build a new capital – on Hallandsåsen in southern Sweden…

Why is it meaningful to have a major Bærtling exhibition right now?

“Partly because a new generation of visitors has never encountered his work. The last time his art was shown at Moderna Museet was the year he died, in 1981. That’s more than a quarter of a century ago. And partly because there is a dawning new interest in abstract art that can appeal to the new generation of artists. The Zeitgeist is a phasing out of postmodernist irony and of the deconstruction of art and society. In the nineties, we saw a new interest in documentaries and analyses of real life. These two strong movements are now being superseded by a renewed focus on modernism and its visionary, forward-looking approach.”

So we want a new idealism?

Yes! You could say that. The works should fill the viewer with energy. At the Moderna exhibition in 2006, visitors could see Jacob Dahlgren. He is strongly inspired by Olle Bærtling. If we look at the exhibition catalogue, one of the central ideas involves a new approach to where Bærtling belongs, historically and geographically.”

Where does his art belong, then: in Kandinsky’s Europe or in American minimalism?

“Something happened to Olle Bærtling in the fifties. Initially, his compositions were restricted to the frame of the work, so to speak. Within the square. But then something happens: he opens up the composition and the picture expands beyond the frame. In that way, he goes against the grain of European modernism and his method resembles that of American minimalism. Compare him to Frank Stella or Donald Judd, where the work incorporates the surrounding space in the composition, while Bærtling’s open shapes extend into the space.”

So what is your opinion? Has Bærtling been completely misinterpreted until now, by being regarded in a European perspective?

“He is American in his eagerness to move on and burst through the boundaries. Meanwhile, he demonstrates an idealism that is more European. He found his own path.

“Throughout his career, he could never wash away the stigma of not having been to art school, and working as a banker for so many years. He was bad-tempered, drastic and excessively critical of the Swedish careful attitude and lyrical disposition. No, for Olle Bærtling energy, dynamism and “open shapes” were the way forward. At the same time, he was characterised by pathos for justice and honesty. Olle Bærtling continues to be an enigma – even to today’s new audiences.”

To the right: Olle Bærtling, around 1950

Photograph: Unknown