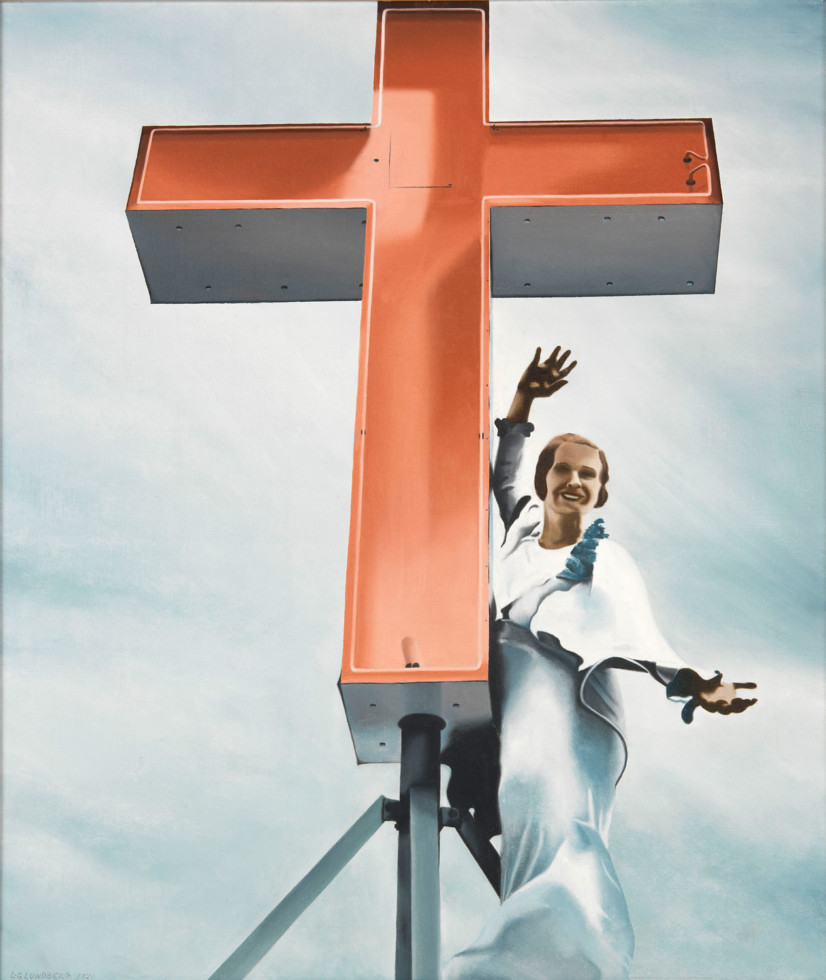

LG Lundberg, Neon Light, 1971 Photo: Åsa Lundén/Moderna Museet

The clouds between us

20.5 2006 – 17.9 2006

Stockholm

They were concerned with perception, the experience of time and space, but also with art as language. Torsten Andersson’s painting The Clouds Between Us from 1966 is a key work in this respect – an abstract sculpture is depicted in a realistic style of painting.

Both an outer and an inner landscape is inherent in the name of the exhibition, The Clouds Between Us. Torsten Andersson’s painting from 1966 bearing this title is the key to unlocking the door to another 1970s, which will be shown this summer.

The painting The Clouds Between Us, in which an abstract sculpture is depicted in a realistic style, was a form of dead end for Torsten Andersson. At this time, the end of the 1960s, he was thinking about the linguistic potential of painting, and what the next step for him as an artist would be. Where was painting heading? The Other 1970s contrasts against the 1970s of political and socially committed art, a zeitgeist that dominates the art from the 1960s and ’70s shown in the Moderna Museet permanent collection. This includes Kjartan Slettemark’s poodle costume in which he ridiculed the art establishment, and Lars Hillersberg’s and Karin Frostenson’s satirical, anti-American painting, where a boxing ring is the arena for global political power struggles. Art as a form of activity is central here, art with an agenda to influence and comment on contemporary society. The political art that arose in the 1970s has perhaps obscured the other 1970s that focused on reflection, form, aesthetic experiments with materials and spatial perception.

The other, low-key 1970s involves entirely different moods and issues than the genre of political art.

Why is it important and meaningful to present the other 1970s at this very time?

It’s time we showed another aspect of the 1970s as a complement, giving more nuance to the picture. Two different temperaments existed side by side, but we are not making any value judgements, saying that one is more important to present than the other,” says Cecilia Widenheim, curator of Swedish and Nordic art at Moderna Museet, and curator of the exhibition The Clouds Between Us – and other works from the Moderna Museet Collection.

She adds that the 1970s are still so close in time that there remains a great deal to explore with regard to the diverse orientations of the decade. The selection for the exhibition comprises works from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. The hub of the presentation will be a work from 2004, Moderna Museet’s recent acquisition, Blue versus Yellow by the artist Olafur Eliasson.

“Many young people today are familiar with Olafur Eliasson’s works and appreciate them, whereas many of the artists who were active in the 1970s are forgotten by the younger generation. This exhibition demonstrates that contemporary artists are inspired by art from the 1970s. Younger visitors will hopefully discover similarities in themes and techniques, for instance the issues of perception and the spectator’s position in relation to the physical context,” says Cecilia Widenheim.

In fact, Olafur Eliasson’s installation Blue versus Yellow was the starting point for the exhibition The Clouds Between Us. It was with the acquisition of this work that the idea of showing another aspect of the 1970s was born. Eliasson’s installation concerns how we become aware of the space we are in, and how our spatial perception is influenced by light and shadow. He creates illusory spaces by playing with the capacity of light to mix colours. All the other works included in the exhibition are in a form of dialogue with Olafur Eliasson’s work.

Cecilia Widenheim was alerted to this other aspect of the 1970s while working last year on an exhibition of Lars Englund, an oeuvre that explores shapes, volumes and a variety of materials – in a play with geometry. A few of his sculptures and reliefs will be included in the coming exhibition about the other 1970s.

The Clouds Between Us features works from the Moderna Museet collection, with one exception – the film My Name is Oona from 1969 by Gunvor Grundel Nelson, which has been borrowed for the exhibition. This is a ten-minute portrait of the artist’s daughter. The images accompany a looped soundtrack in which the little girl’s voice saying “My name is Oona” is repeated like a magic spell, while dreamlike images float by. Both the outer and inner worlds are materialised and the film oscillates between the reassuringly familiar and the eerily unfamiliar. This is especially poignant in the scene where the girl rides across a field on horseback, with the wind blowing in her hair and her princess cloak, towards the unknown.

In one of the galleries visitors encounter themes such as body and landscape, for instance in Barbro Bäckström’s sculpture Backs, made of metal wire, and Hreinn Fridfinnsson’s photographic suite House Project, a house in an Icelandic landscape with no other human traces. A closer scrutiny reveals that the house is inside out, so the inside unexpectedly adorns the facade. The gallery also features geometric sculptures made of natural materials – wood, bundles of twigs and rope – by Lars Millhagen who associates to rituals, and Jan Håfström’s narrow oblong painting Long Island, which evokes ditches, tracks and earth layers.

“Several of these artists often worked in the public domain on a large scale, for instance Lars Englund and Elli Hembert, and their art is not entirely devoid of a political undertone. These artists, however, were concerned with modifying the new urban environment,” Cecilia Widenheim explains.

The exhibition also looks at the unassuming that grows in significance when regarded more closely. Drawings by Anna Sjödahl show ordinary, commonplace objects from everyday life – scissors, a kitchen window and cutlery. A milk-white plexiglass pane over the panel gives them a dreamlike shimmer and they appear to the spectator as memories of something that is constantly there, nearby, if only we choose to really see it.

“The treasures of the world,” says Cecilia Widenheim.

Barbro Östlihn’s works are painted from photographs she took on her walks through urban quarters, for instance a shadow across a facade and a segment of a monument in a graveyard. The paintings have a grid-like structure, where no square is like the other.

“She bakes time into squares and captures a moment, and holds it eternally,” as Cecilia Widenheim describes it. “Her images don’t convey a particular message; instead they are a form of mediation, vibrating silently and allowing the viewer to linger and float away on a daydream.”

On 20 May we can step into this other 1970s and explore landscapes where no boundaries exist but those we draw up ourselves.

Curator: Cecilia Widenheim