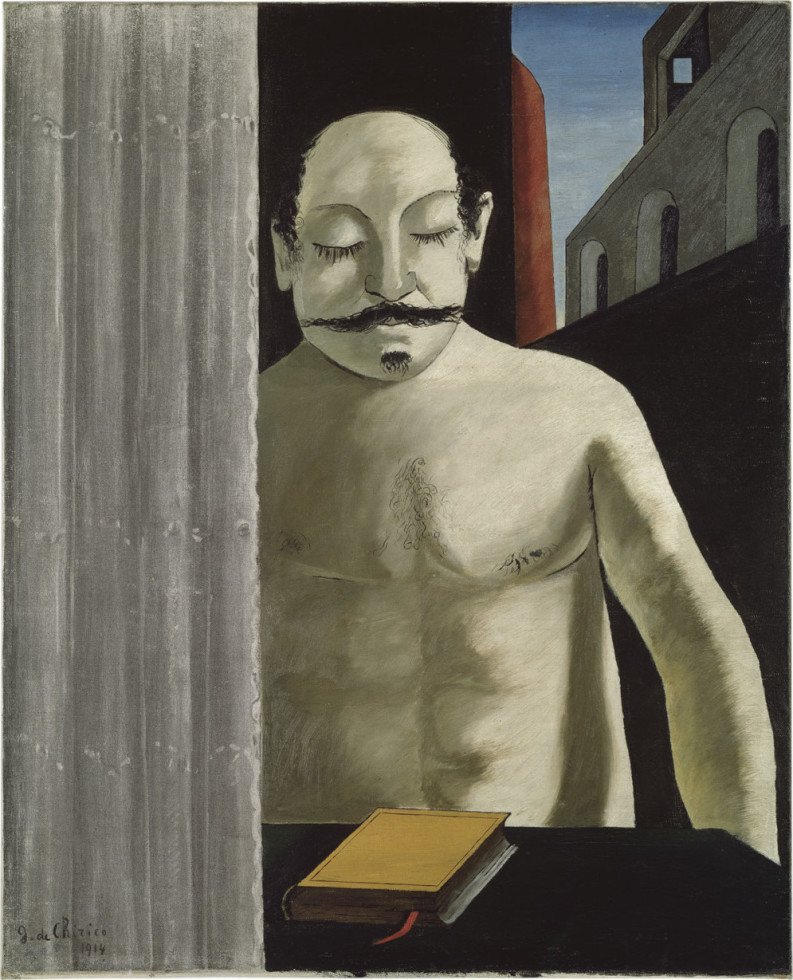

Giorgio de Chirico, Barnets hjärna, 1914 © Giorgio de Chirico/2015 Bildupphovsrätt 2015

Surrealism

There were various expressions, but they all originated in Paris, where the author André Breton wrote the first Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. The city also attracted young writers and painters from the Dada movement. They used automatic writing and dream resumés in attempts to tap into the subconscious. The ambition was to dissolve dream and reality into an absolute reality – a super-reality (surreality). The surrealists wanted to change life and society, and liberate the individual.

Giorgio de Chirico is the primary pioneer of surrealist painting. In what he called his ‘metaphysical paintings’, made before the First World War, de Chirico portrayed a fictive, eerie world with near-photorealism. Salvador Dalí, René Magritte and Yves Tanguy used the secret imagery of dreams in their hyperrealist figurative style, while Joan Miró created a universe of symbolically charge abstract signs. Max Ernst experimented with different techniques, including frottage and collage, to achieve painting beyond painting, where transformations and metamorphoses were central elements. He forced himself to react to the unexpected and surrender himself to chance.

In sculpture, Hans Arp developed a biomorphic style, while Giacometti’s claustrophobic works are charged with both violence and eroticism. Meret Oppenheim and Wilhelm Freddie produced surrealist objects that can be seen as three-dimensional collages of everyday items from diverse contexts, evoking dark and sexual fantasies. Bellmer’s photographs of dolls address taboos, desires and sadistic themes. Surrealism was the first movement in the 1920s to use moving images as a new medium.

Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp abandoned painting in the traditional sense in 1913, when he was only 26. The year before, he had painted Nude Descending a Staircase. This work was exhibited at the Armory Show in New York in 1913, where it attracted a great deal of attention. The exhibition is now legendary for having introduced cubism and European avant-garde in the USA. Yet, Duchamp’s static picture owes more to Eadweard Muybridge’s photos of moving bodies than to cubist imagery.

Duchamp worked as a librarian in Paris for a while, but when the war broke out in Europe, he moved to New York, where he continued creating ready-mades, combining everyday found things into new, enigmatic objects. Eventually, he went even further, by taking objects from their normal setting and presenting them in an art context, thereby challenging the concepts and notions of what art is and can be. Duchamp never exhibited his ready-mades but kept them in his studio, with one exception: In 1917, he submitted his inverted urinal, Fountain, signed R. Mutt, to an exhibition at the Society of Independent Artists in New York. The work was turned down, despite promises that all entries would be accepted.

Few of his early “original” works have been preserved. Duchamp poses the question of whether an artist can create works that are not art. With his cool, critical attitude to originality, authorship and the artist role, his emphasis was on art as an intellectual activity, rather than an aesthetic one.

Duchamp and surrealism

With Surrealism & Duchamp, Moderna Museet continues the dialogue between Duchamp and other artists in the Museum’s collection. As one of the most radical early-20th century artists, Marcel Duchamp, along with Giorgio de Chirico and Max Ernst, was a vital source of inspiration for the surrealist artists. Duchamp had introduced chance and games in his work at an early stage. His ready-mades, which combined things he found into new objects, inspired surrealists in the 1930s to develop their symbolically-charged “surrealist objects”.

Duchamp did not exhibit in Europe until the 1930s, but André Breton had introduced surrealist circles to his work already in 1922. Breton, who was the leader of the surrealist group, had written an overview of Duchamp’s works in 1934, stressing Duchamp’s unique importance to the art of the future. At the time, Duchamp had withdrawn from the artist life and devoted himself to mastering the art of chess. He declined the constant invitations to take part in the surrealist group, stating that: “All those exhibitions of painting and sculpture make me ill.”

He did, however, participate in an exhibition of surrealist objects at Galerie Ratton in Paris. In 1937, he designed the entrance to Breton’s gallery Gradiva in Paris, modelled on the contours of a couple embracing. The following year, Duchamp also designed the legendary surrealist exhibition Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, organised by André Breton and Paul Éluard at Galerie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This was the first completely staged art presentation in the history of art exhibitions. Duchamp’s setting invited visitors into a breathtaking world of dreams, obsessions, surprises and dangers.

Duchamp himself was inspired by the work of the surrealists when creating his last major project, Étant donnés (1946–66) an installation incorporating the powerful erotic fantasies that were also central to surrealism. Although Marcel Duchamp’s work was periodically close to the surrealist artists, he remained independent and trod his own path throughout his career.

Curator: Iris Müller-Westermann