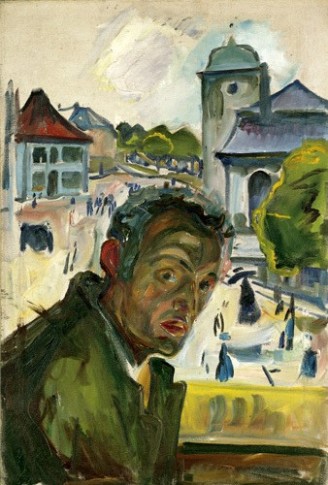

Edvard Munch, Self-portrait with Cigarette, 1895 © Munch-museet/Munch-Ellingsen Gruppen/BUS 2005. Tillhör Nasjonalmuseet for Kunst/Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo

Towards a new aesthetic

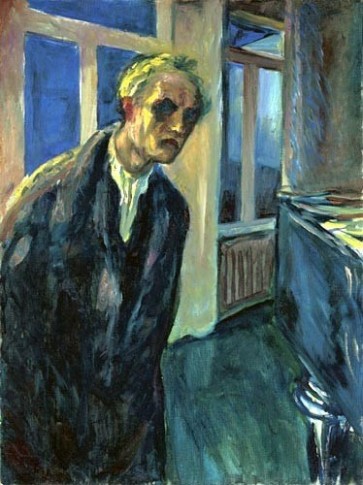

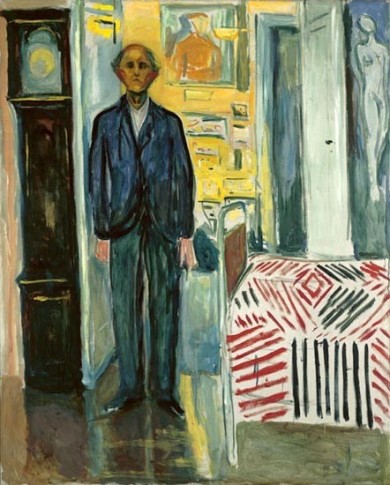

We can follow Munch’s search for a new pictorial language in his self-portraits Vision (1892), Self-portrait Beneath a Female Mask (circa 1893) and Self-portrait with Skeleton Arm (1895). Life, Love and Death – central themes for the symbolists – are charged with Munch’s own meanings. The relationship between the sexes takes centre-stage.

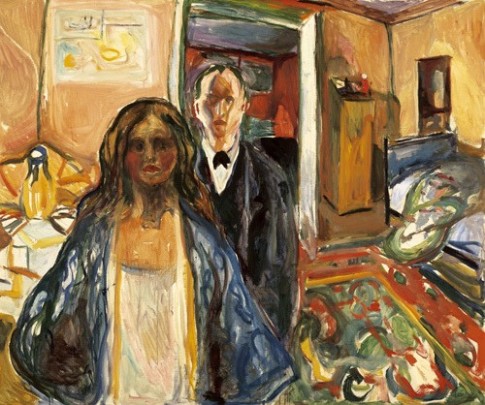

In Woman. Sphinx (1893-94) elements from the previously mentioned self-portraits recur. The swan has turned into a woman in white, the female mask is now a nude, red-haired woman, and the skeleton arm reappears in the form of a woman in black.

Similarly, Dagny Juel Przbyszewska (1893) and Self-portrait with Cigarette (1895) may reveal how Munch defines his role as an artist in dialogues between paintings. In the former, Dagny Juel embodies the modern, self-conscious woman, a theme he comments on in Self-portrait with Cigarette, where he is portrayed as a thinker – not a painter. He uses colours to evoke an air of spirituality and inspiration, and puts himself forth as a representative of a new art that does not imitate reality but establishes the inherent reality of the image itself.