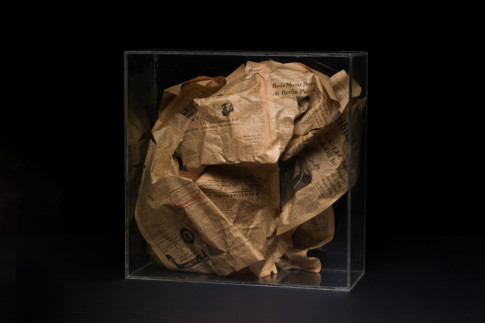

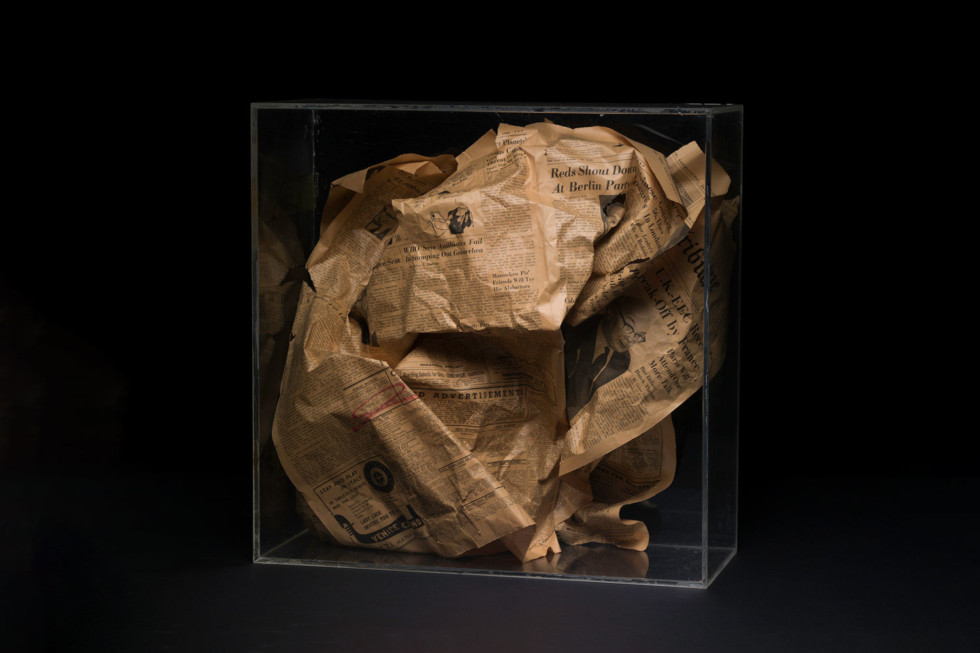

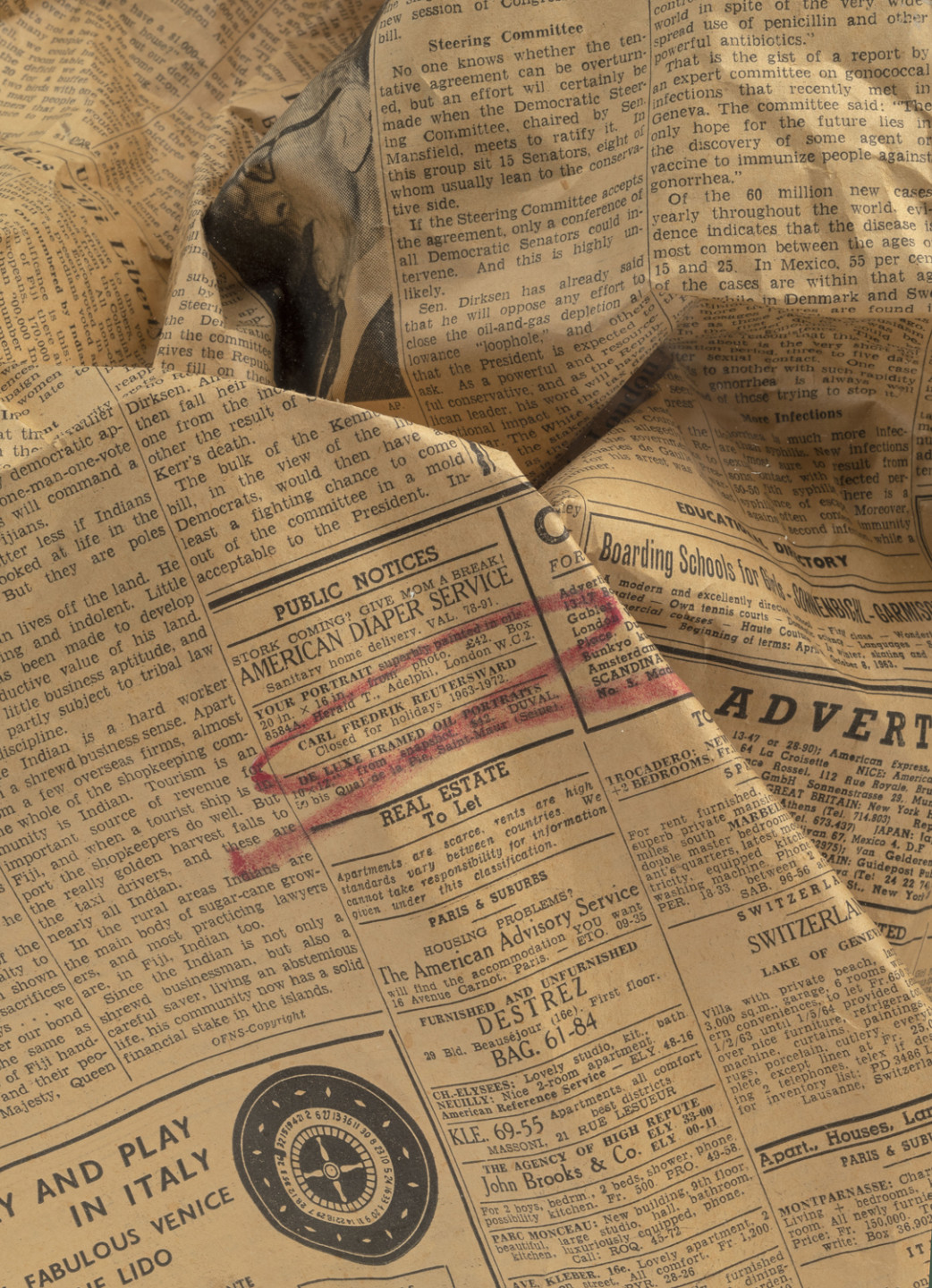

Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, New York Herald Tribune, 1963 From the series ”Kilroy”, 1963 © Carl Fredrik Ruterswärd / Bildupphovsrätt 2018

Essay by Curator Andreas Nilsson

Text: Andreas Nilsson

Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd’s (1934–2016) career spanned almost seven decades, multiple pseudonyms, and most media. The exhibition ”Alias: CFR” presents at least two (but probably more) sides of his multifaceted work. ”Alias: CFR” focuses in part on an intricate installation, the object group ”Kilroy” (1963–1972), and in part on a series of expressive, large-scale drawings the artist made after a stroke in 1989 forced him to work with his left hand instead of his right.

From the late-1950s through the 1960s, Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd was part of a vibrant avant-garde art scene that has to some extent become synonymous with the early years of Moderna Museet.[1] Already by its inauguration in 1958, Reuterswärd appeared at Moderna Museet with his performance/happening ”Dialogue with Fox, Physical Exchange”, where he appeared well-dressed, on stage and conducted a conversation with a fox.[2] He was one of a number of artists such as Öyvind Fahlström, Ilmar Laaban, and Åke Hodell who—inspired by others such as Fluxus, Dada, Marcel Duchamp, and John Cage—worked with most of the forms of expression available to an artist. Under the pseudonym of Charlie Lavendel, Reuterswärd took part in a Fluxus event arranged by Bengt af Klintberg in March of 1963 at Alléteatern, a theater in Stockholm. His contribution to the experimental art performance was to hide in the dark with his friend Daniel Kallós and spray lavender oil throughout the theater, which caused everyone in the audience to fall asleep. Earlier the same year, Reuterswärd auctioned off a ten-kilo pike fish at Moderna Museet. The artist and satirist Lars Hillersberg bid for the fish by drunkenly shouting “Denmark!” The work Reuterswärd and his friends were doing was frequently seen as nonsense, although it had, in addition to humour, elements of social and cultural criticism as well. But it required observers to open their minds and look beyond the immediately obvious.

Kilroy (or Nine Years’ Holiday)

It is not entirely clear where Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd’s comprehensive and elusive project ”Kilroy” begins and ends either in time or space. Moderna Museet’s collection includes a sketch drawing for ”Kilroy” that is signed and dated “CFR 1960,” although that note is likely misleading.[3] A more possible time frame for the project is suggested by the public notice Reuterswärd published in the ”New York Herald Tribune” in January 1963:

CARL FREDRIK REUTERSWÄRD Closed for holidays 1963–1972.

During this proclaimed holiday period, Reuterswärd intended to create nine objects under the collective title of ”Kilroy”. The woman at the paper to whom he dictated his notice commented, “You must be very happy.”[4] At the time, however, Reuterswärd had come to see the established art scene as oppressive, and perhaps his holiday should instead be understood as a necessary break from the increasingly commercialized and compromising climate in the artworld. The advertised holiday was serious as well as humorous, and asserted both the artist’s freedom and his rejection of established patterns. But perhaps it should be interpreted primarily as Reuterswärd taking a holiday from himself, an opportunity for both internal and external exploration, and he would not allow his name or his role as an artist to get in the way of that. It may also be that Reuterswärd’s conservative and rather conventional upbringing indirectly brought on this break, which provided an opportunity for both seclusion and independence.

The advertised holiday was serious as well as humorous, and asserted both the artist’s freedom and his rejection of established patterns.

In 1962, the year before he published the notice in the ”New York Herald Tribune”, Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd had noticed the phrase “Kilroy was here” scrawled on a wall in New York next to a simple drawing of a face peering over a wall. It wasn’t the first time he had seen the words. In his autobiographical childhood memoir, meaningfully entitled ”Look, I Am Invisible!”, he mentions in a passing how even as a young teenager in Stockholm he noticed how “Kilroy had written ‘was here’ in lipstick on the mirror above the sink” in the bathroom of a music café on Götgatan.[5] The phrase “Kilroy was here” can be traced back to the Second World War, when U.S. American soldiers scribbled it on walls wherever they happened to be for the moment. Reuterswärd later began to play with the idea of using the name Kilroy as a signature for a group of objects. Kilroy was everyone and no one, leaving his name for anyone at all, and Reuterswärd has compared the moniker with the main character in James Joyce’s ”Finnegans Wake” (1939), H.C.E.—Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, also known as “Here Comes Everybody.” The complex ”Kilroy” project spanned nine years and countless techniques and materials—“sculpture, objects, bronze, lead and mercury, swallowed lead and spat up again, a laser beam lights up a heart (really, of gold), ‘closed for the holidays for nine years,’ stepladder on a bit of mirror that reflects upward and down….”[6]

In the press release for his 1972 exhibition ”KILROY: Objects & Holograms” at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, the artist wrote:

When you see yourself in my pupil and I see myself in yours, not only an identification takes place but also a meeting between two kinds of time. The unique biological I-time and the universal. Between these two times I sense “an everyman’s time” KILROY’s time. It is in that time—if only for a moment—that man’s fundamental isolation is eliminated: I am in your time. The need for that moment is the basic theme of KILROY.

The central aspect of the project seems to be the space between—the space between you and me, the person between two imagined monikers, the time between past and present, the gap between art and life, and (to make the connection with Reuterswärd’s poetry) the spaces between the letters of the alphabet. His attempts to capture these interstitial spaces and what they might actually contain frequently leave the viewer in a (satisfying) state of searching and floundering. The carefully considered disposition of the objects that make up the core of ”Kilroy” contrasts with an ostensibly intuitive working method in which an idea or a feeling leads to some action, which then evolves into an idea, which in turn results in an action. It calls to mind, for example, how Reuterswärd shredded the pages of the Swedish Academy’s Glossary and baked it into a loaf for the art work ”Snille och Smak: Thinking Is Digestion (Wittgenstein)” (1963). The work encompasses, in a way that is hard to explain, both intellectual respect and arrogant playfulness.

Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd was born in 1934 under the sign of Gemini, and the many pseudonyms he adopted during the course of his life can certainly be understood as aspects of the twin flame or soulmate we perhaps all have. This juxtaposition of a person’s dual identities can also be found in the miniature work ”Booth of Us: New York Dialogue” (1962), a board game which holds six identically clad men (gray suit, white shirt, red tie) in phone booths. The title refers to both the man speaking and the one listening on the other end of the line.[7]

In his description and analysis of ”Kilroy”, Ulf Linde has written extensively about the twins Castor and Pollux from Greek mythology.[8] After Castor’s death, Pollux begs his father Zeus to reunite him with his brother. His wish is granted on the condition that the two must alternate their days on Olympus and in Hades. Reuterswärd used the heading “Castor” for four objects entitled ”The Hand” (1962), ”The Seal” (1963), ”The Vacuum” (1963), and ”The Dog’s Leg” (1972). “Pollux” united ”The Steps” (1963), ”The Eye” (1968), ”The Sail” (1964), and ”The Stone” (1962). A ninth object, ”Kilroy’s Heart” (1962), stands alone. Together they make up the ”Kilroy” group and establish the link between two souls, with Castor symbolizing “Me” and Pollux symbolizing “You.”

The choice of materials suggests something both grounded and airborne, and a quick glance at the objects’ simple titles also makes the connections between the physical body, the senses, involuntary throwing up, and nature. They engender a symbiotic relationship between the intuitive and the intellectual, the unconscious and the conscious, the tactile and the conceptual. A visual poetry emerges in which the objects and the words are interwoven, linked together, leading down meandering thought paths, and at the same time an elusive feeling becomes palpable. It is in these links that the installation takes form and comes to life with the help of both natural materials, ready-made objects, and objects made by the artist. An existential condition can unequivocally be read in the work—a condition that becomes even more obvious, and at the same time more complex, if we compare with the original version of ”Kilroy” created in the period 1963–1972 with the one Reuterswärd made as late as 2000 under the title ”Kilroy II”.[9] The two works are essentially identical, with the key difference that the sail in the first version lies collapsed in a formless pile, while in the later version the sail is rigged and seems to have caught the wind. What are observers to make of a change like that executed after an interval of thirty years? It is as though Kilroy has reawakened after a long sleep, and is once again ready to tease the observer, or perhaps just to give notice that “Kilroy is here!” The fact that the twined rope that anchors the sail has often been likened to an umbilical cord underscores the notion of a rebirth. What is more, the idea for the rope came to Reuterswärd at the time of his daughter’s birth.

It is as though Kilroy has reawakened after a long sleep, and is once again ready to tease the observer, or perhaps just to give notice that “Kilroy is here!” The fact that the twined rope that anchors the sail has often been likened to an umbilical cord underscores the notion of a rebirth. What is more, the idea for the rope came to Reuterswärd at the time of his daughter’s birth.

However, ”Kilroy” should not only be understood as an existential philosophical project. A highest political dimension is also found, for example in ”The Eye” – a three-part object in plexiglass. Its form reminds of a circle surrounded by a pair of parenthesis. Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd was inspired by the design of the discussion board used in the 1973 peace talks in Paris between the United States and North Vietnam. It becomes a strong reminder of what Reuterswärd termed a “cynical aestheticism” in society.

Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd was an early adopter of new techniques such as lasers and holograms in his art. Using lasers allowed him to expand the sculptural object and its potencies to become something both material and immaterial, both enduring and fleeting. The laser light points straight down at Kilroy’s heart—it illuminates the encounter between Me and You, Castor and Pollux. As early as 1962, Reuterswärd was using the laser as a tool for creating more enduring poetic works for the ”Kilroy” series. These included sheets of Plexiglas with ”KILROY” engraved on them with a laser.[10] This melding together of art and technology could be seen at the same time in the organization Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), which was founded on the goal of bringing together artists and engineers. E.A.T. was officially launched in 1967 by the engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer together with artists Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman. The year before, Klüver and Rauschenberg had done the performance project ”9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering”, the first large-scale collaboration among artists, engineers, and scientists.[11] It was also Klüver who showed Reuterswärd a laser beam that could cut through the air. “My mental perception changed,” he said. “Here was the tool that broke with all traditions!”[12] Reuterswärd conducted his first experiments in January 1965, and in 1969 he wrote in ”Laser-journalen 1962–1972”:

In my work with lasers I have discovered, among many other things, how puzzling a little spot of red laser on a wall can seem. People are accustomed to immediately identifying a light’s source, its trajectory, and its reflections. With laser light, one can ensure the viewer sees only the reflection. Experiencing something they’ve never experienced before immediately makes them wonder. “Where is that light coming from? Who is producing it?” And if you can’t see a person, a light source, or light beams, you might well believe it’s some kind of magic.[13]

Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd was an early adopter of new techniques such as lasers and holograms in his art. Using lasers allowed him to expand the sculptural object and its potencies to become something both material and immaterial, both enduring and fleeting.

In connection with ”Kilroy”, it is interesting to note that in 1967 Susan Sontag wrote her critical essay “The Aesthetics of Silence,” in which she expounds on withdrawal and the application of silence in the practice of art, both in relation to ideas about ready-made objects and performance.[14] Sontag maintains that silence does not negate the work; on the contrary, it charges it with greater power and authority—it becomes “a certificate of unchallengeable seriousness.” It should be noted that the silence discussed here does not imply that the artist ceases to create art, but instead that the artist continues to speak, but in a way that causes the observer to perceive and read the art in a different way either sensory or conceptually.

Silence shifts the observer’s focus, and what is perhaps one of Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd’s best-known poetry publications, ”Prix Nobel” (1960–66), includes only punctuation marks without the words. Reuterswärd frequently utilized a similar method both in his visual art and in his poetry. In several of his sculptures, the spaces between words and letters have been allowed to create the actual form. Regarding these “inter-letters”, Sontag writes in her text “The Unseen Alphabet”:

Inter-letters are silent. They pivot and fold (arbitrarily), instead of sounding. … These forms have the status of ”parts or element” of a larger system: the unseen alphabet. We are invited to savor the parts, knowing they are parts, without being able to envisage (or represent) the whole.[15]

An intellectual retreat characterizes the (holiday) project ”Kilroy”, and can be related on different levels to Sontag’s ideas about the artist’s silence and the object’s potential to speak. ”Kilroy’”s activation of the objects charges them with both mysticism and a content of their own—content that the Kilroy alias serves to further automate and distance from Reuterswärd as a person. In the collision between “the spirit” and “the material,” to borrow Sontag’s terminology, a discussion emerges in the project about the link between artist and artwork. And while these ideas can seem both romantic and dated today, I believe that in a (perhaps ironic) way they underscore the sense of freedom Reuterswärd found in his various aliases.

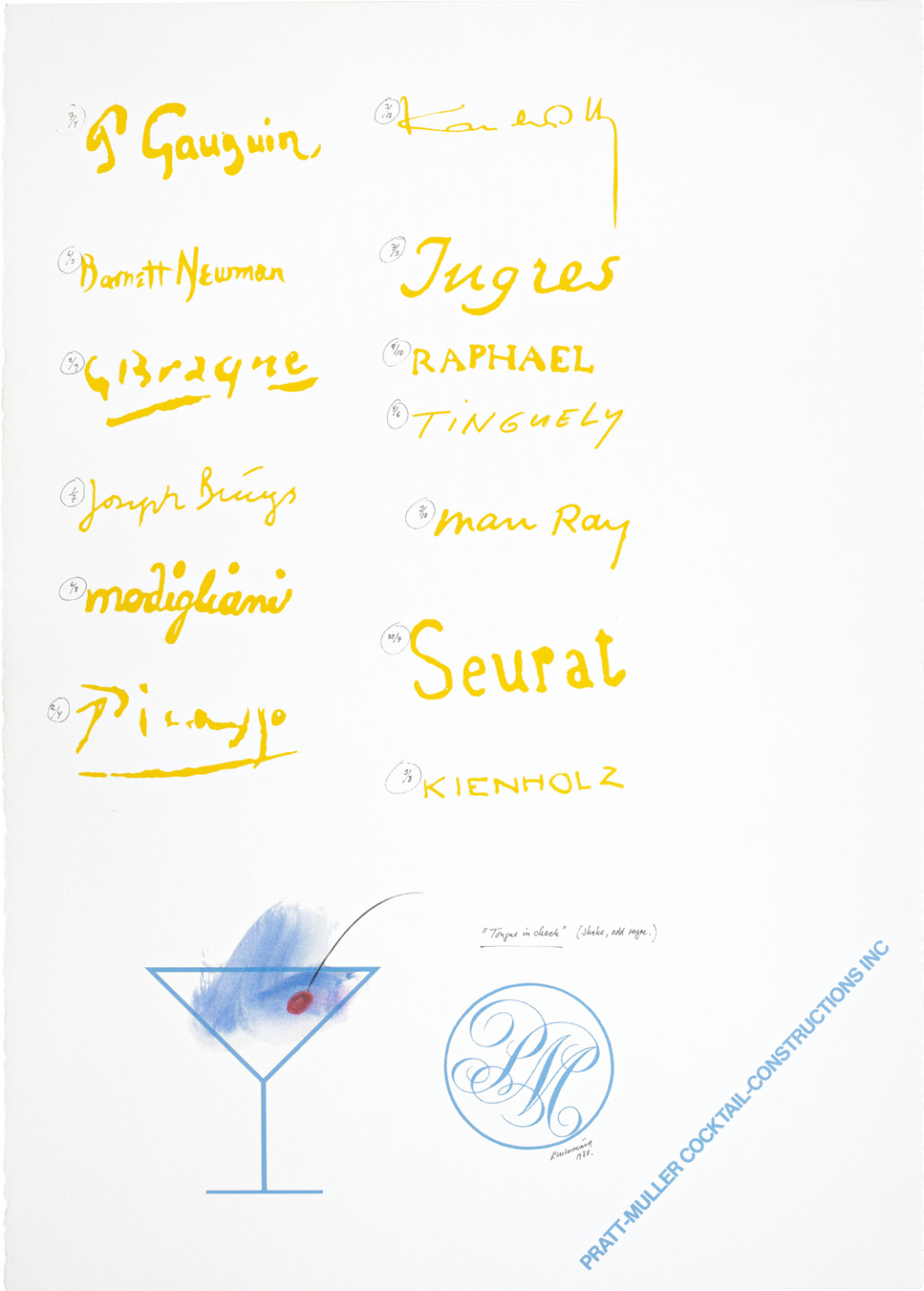

The relationship between artist and artwork calls to mind the philanthropist and entrepreneur Dr. Arnold Forel Pratt-Müller, whose corporate empire, founded in 1973, encompassed words, objects, letters, inventory, and airline tickets. Dr. Pratt-Müller, who was early to appreciate the importance of icons in western art and culture, asserted, “We cannot go on haggling over such unmanageable and sentimental rubbish as paintings and sculptures. Why not concentrate on the most important element of a work of art, The Signature.”[16] This conviction formed the backdrop for the creation of “Pratt-Müller Super-Elastic Signatures,” which gave the owner of such a signature (such as Salvador Dalí or Jackson Pollock) the right to physically and symbolically stretch it to whatever value they desired. With the purchase of three signatures, the buyer also received a piggy bank that could be blown up to any size at all.

Dr. Pratt-Müller and his empire are, unsurprisingly, a humorous and barely concealed critique of the commercial art market staged and orchestrated by Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd himself. And here it also becomes interesting to note that during a long portion of his career Reuterswärd drew a large number of portraits of well-known artists, authors, and thinkers. In addition, since 1962, “owing to the lack of new inventive artists in the western world,” Kilroy has generated a number of new artist names, which can in turn be traced back to Dr. Pratt-Müller’s empire. These names are published in ”The Complete List of Invented Artists” (1973). Two more works in the exhibition ”Alias: CFR” belong to Dr. Pratt-Müller’s empire. In the painting ”Zwei Fliegen auf einen Schlag” [Eng. ”Two birds With One Stone”] (1975), more or less famous artists’ names swarm past, all with their first syllable replaced with “Pi”—after Picasso, the artist best known to the general public—“Pindinsky,” “Pirico,” “Pichamp,” “Pincusi”…. The object ”Jesus Christie’s Halleluja Sotheby-Parke Bernet!” (1973–74) is a full-sized auction podium whose title plainly references what were then and continue to be the major auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby-Parke Bernet (now Sotheby’s). On the upper portion of the podium we can read in Latin “Ora pro nobis” (pray for us), which clearly refers to the similarity between the auction podium and a church pulpit. At the foot of the sculpture, Kilroy can be seen peeking over a “for sale” sign.

Dr. Pratt-Müller and his empire are, unsurprisingly, a humorous and barely concealed critique of the commercial art market staged and orchestrated by Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd himself.

Later Works (or CFR’s Left Time)

The fall of 1989 is often and understandably enough considered an important inflection point in Carl Fredrik Reuterswärds’s life. He had a stroke that left him unconscious for a couple of months. After regaining consciousness, he needed to relearn many abilities from scratch—memory, speech, mobility. In December 1989, Reuterswärd began drawing again, having been forced to switch from his right hand to his left. Drawing after drawing. Simple figures on a white background. Stick figures. Little birds. Various objects (some that he needed, but couldn’t express verbally). Certain subjects, such as the knot and the revolver, can be recognized from his earlier work. With unrelenting will, the artist seems to be carving out a new expression. A new Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd takes form. At the same time, this new identity should perhaps be regarded as yet another of the various aliases he relied on during his active career to move among different genres and artistic styles with apparent nonchalance. The difference with these later works, however, is the sensibility that emerges—the intellectual seems to have given way for a more emotional and expressive style. Reuterswärd seems powerfully present, and at the same time he seems to be navigating through a kind of persistent dream state. From the first drawings he made after his stroke, some people have drawn parallels with the work of Fridolin Vogelsang, yet another of Reuterswärd’s many aliases.[17]

Vogelsang was born in East Berlin in 1938, and in the mid-1980s (1983–88) he created a number of simple, fragile portraits in an obviously shaky and untrained hand. The faces are drawn in black crayon with marks that seem to be in the process of transformation and dissolution, both against the white paper and against the drawing’s own intrinsic subject. In the wake of Reuterswärd’s stroke, it seems to have been Vogelsang’s style that provided the basis for the development of the new work.

The exhibition ”Alias: CFR” features a couple of large-scale pastel drawings from the late 1990s. Their visual style reveals another kind of liberation than we have seen in Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd’s more conceptual work from the 1960s and 70s. The works are driven on by a movement that is both compositional and purely technical. Looking at these pictures, we can almost physically feel the application of the pastel strokes, as though Reuterswärd was in a hurry as he worked. They radiate enthusiasm. In these scenes, mythological figures and acrobatic exercises are prominent, and we can discern both an existential and a sexual dimension. The drawings reveal a sense of freedom but also of anxiety, perhaps of being haunted by the struggle of the artist’s later years. In ”The Hanged” (1998), we see a person balancing upside-down on one hand, torso and legs entwined around a post (or perhaps the post goes straight through the body) that does not reach the ground. The scene is simultaneously melancholic and hopeful, as though the figure is caught in existential limbo, a balancing act that suggests rebirth.

Surely it is no coincidence that it is the left hand that is anchored to the ground, while the right hovers just above it. The drawing ”Gulliver” (1999/2001) radiates a more aggressive drama. Almost the entire picture surface is filled with the figure of an imaginative monster that walks on all fours with wings spread and sex exposed. Its eyes are wide open and in its gaping mouth the bared teeth are clearly visible. It stretches out its right foreleg as though preparing to take off. Blue and white crayon strokes strike out like lightning from the head and body, animating the picture.

With unrelenting will, the artist seems to be carving out a new expression. A new Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd takes form.

One of Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd’s undoubtedly best-known projects is ”Non Violence”, the revolver with its barrel tied up in a knot. The first version of the sculpture was installed outside the United Nations headquarters in New York in 1988. The artist had previously used the knot to symbolically strangle pens in works such as the drawing ”Medium’s Memory” (1963). The knotted barrel of the revolver can be interpreted as an expression of pacifist resistance and also as a way of mocking masculinity, the gun transformed into a flaccid and limp phallus. Bengt Adlers, a poet, artist, and close friend to Reuterswärd, offers another interpretation that is worth considering: the old practice of tying a knot in a handkerchief as a reminder of something important. With this custom in mind, the observer can perceive the knot as not only an act of resistance, but also an exhortation to remember—to remember not to resort to violence, or to go to war.[18] After his stroke, Reuterswärd continued drawing versions of the revolver, though the forms and lines became softer (no doubt in part because of his disability) and more fragile, and at the same time more complex. At about this same time he also created a series of sexualized pictures that express increased mobility and vitality as much as they do lust. The revolver recurs again in one of the later big pastel drawings called ”Non Violence” (1998). Here the barrel isn’t knotted, but instead seems to be shooting out a person dressed in blue and wearing a tall hat. In front of this figure stands another white one with a tail. With a lit candle in hand, the white figure seems to be awaiting the other’s arrival.

Even if the visual style of Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd’s later drawings differs from his earlier idea-based exercises and works, they are all tied together by the artist’s continual exploration of new styles and approaches. The intricate (role) play among the various aliases and pseudonyms that went on throughout Reuterswärd’s entire life boiled down in the end to the man himself, the mysterious and dreamlike united with hope, existential doubt, and not least humor. Not surprising, then, that the two-faced god Janus, whose one face can look forward into the future and the other back into the past, appears in the artist’s drawings from the late 1990s. Reuterswärd was a one-man collective for whom a single signature style was considered a fraud. Who was Kilroy? Or Fridolin Vogelsang? Charlie Lavendel? Dr. Arnold Forel Pratt-Müller? Everyone and no one. C.F.R. as H.C.E., ”Here Comes Everybody!”

References

[1] For an overview of the art scene in Sweden during the 1960s, see Leif Nylén, ”Den öppna konsten – Happenings, instrumental teater, konkret poesi och andra gränsöverskridningar i det svenska 60-talet”, Stockholm: Sveriges Allmänna Konstförening, 1998.

[2] ”Dialogue with Fox, Physical Exchange” was presented on November 27, 1958, at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, which was inaugurated in the same year on May 9.

[3] Moderna Museet, inv. no. MOM/2015/107. In addition to the fact that the work is signed “CFR 1960,” the note “CFR 1971” can also be found on the paper on which the sketch is mounted. Art historian and critic Thomas Millroth asserts that the sketch is in all likelihood dated after the fact, and that Reuterswärd had simply gotten it wrong. The author in conversation with Thomas Millroth, Malmö, August 16, 2018.

[4] Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, ”Closed for Holidays Memoarer”, Stockholm: Natur och Kultur, 2000, p. 88.

[5] Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, ”Titta, jag är osynlig!”, Stockholm: Gedins, 1988, p. 139.

[6] Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, ”Closed For Holidays Memoarer”, Stockholm: Natur och Kultur, 2000, p. 68.

[7] An alternative title that has been ascribed to the same art work is ”New York Boothing. See Stil är bedrägeri – Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd”, eds. Gert Fors, Tonie Lewenhaupt, Thomas Millroth, Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, Malmö: Bokförlaget Arena, 2004, p. 66.

[8] Ulf Linde, “Kilroy, Castor och Pollux,” ”Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, 25 år i branschen”, Moderna Museet catalogue no. 149 with supplement, Bern: Benteli Verlag & Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 1977.

[9] ”Kilroy I” (1962–72) is in the collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris. ”Kilroy II” (2000) is in Moderna Museet’s collection.

[10] Andrew Pepper, “CFR, Kilroy och laser,” ”Stil är bedrägeri – Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd”, eds. Gert Fors, Tonie Lewenhaupt, Thomas Millroth, Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, Malmö: Bokförlaget Arena, 2004, pp. 104–08.

[11] ”9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering” was held at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York between October 13 and 23, 1966. Participating artists: John Cage, Lucinda Childs, Öyvind Fahlström, Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Robert Rauschenberg, David Tudor, and Robert Whitman.

[12] Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, “Rubies and Rubbish: An Artist’s Notes on Lasers and Holography,” ”Leonardo”, Vol. 22, No. 3/4, 1989, p. 343.

[13] Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, ”Laser-journalen 1962–1972”, 1972, pp. 4–5. Moderna Museet archives F1A:65.

[14] Susan Sontag, ”The Aesthetics of Silence”, ”Styles of Radical Will”, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969.

[15] Susan Sontag, “The Unseen Alphabet”, ”Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd”, ed. Nina Öhman. Moderna Museet catalogue nr 196, Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 1985.

[16] Dore Ashton, “As I Was Saying,” ”Caviart: The Ultimate Selection from the Pratt-Muller Empire”, ed. Faith M. Towle, Bussigny/Lausanne: Pratt-Muller University Press, 1983, p. 8.

[17] See, for example, Thomas Millroth, “Ett udda men framsynt tema – Fridolin Vogelsangs teckningar” ”Stil är bedrägeri – Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd”, eds. Gert Fors, Tonie Lewenhaupt, Thomas Millroth, Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd, Malmö: Bokförlaget Arena, 2004, pp. 170–72. See also Magnus Jensner, “The Second Coming of CFR,” ”Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd”, eds. Magnus Jensner and Evalena Lidman, Helsingborg: Dunkers kulturhus, 2003, p. 10.

[18] The author in conversation with Bengt Adlers, Malmö, September 13, 2018.

Andreas Nilsson

Andreas Nilsson is the curator of the exhibition “Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd – Alias:CRF”. He has been at the museum since 2009 where he has curated “The Moderna Exhibition 2014 – Society Acts”, co-curated “Public Movement – On Art, Politics and Dance” (2017–2018), and co-curated “Objects and Bodies at Rest and in Motion” (2015–2016), among others. He is also the program coordinator for the lecture series KHM x MMM.

Catalogue ”Alias: CFR”

The richly illustrated exhibition catalogue will feature an essay by curator Andreas Nilsson and poetry by Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd. 128 pages.

Buy the catalogue: Moderna Museet Shop