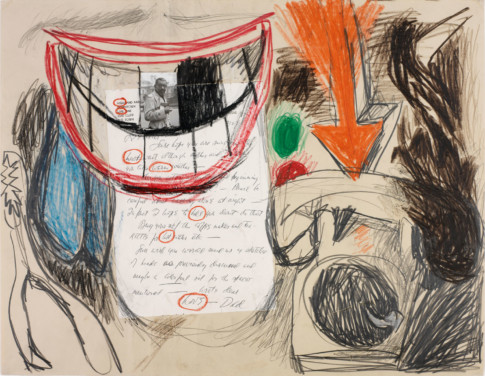

Lee Lozano, No title, 1964 © The Estate of Lee Lozano. Courtesy Hauser and Wirth.

Lee Lozano’s Investigations

Text by Iris Müller-Westermann published in the exhibition catalogue.

“Making Art Is the Greatest Act of All”

In just twelve short years, she produced a radical, impressively independent, often obscene, extremely provocative, and multifaceted body of work that adopted ideas from Minimal and Conceptual Art, yet always managed to subvert them. During those years, Lozano took her place in New York’s male-dominated art world with great self-confidence. Some of the other female artists who made names for themselves there at the same time were Eva Hesse, Lee Bontecou, Jo Baer, Joan Jonas, Yayoi Kusama, Louise Bourgeois, and Agnes Martin. In recent years, well-deserved and long-awaited retrospectives have been devoted to many of them.

After completing her studies at the Art Institute of Chicago, Lozano left for New York in 1960, later calling it “one of the big idea centers.”1 Her extensive output testifies to the fact that the artist must have worked at a maniacal pace. In one of her notebooks she wrote, “Making art is the greatest act of all.”2 She went through distinct artistic phases in rapid succession. From figurative paintings with an expressionist undertone, she moved to surrealistic drawings and paintings in 1961 that focused on the body, sexuality, and violence. In 1963 she began to produce enormous pictures of anthropomorphized tools, switching to an almost totally monochromatic palette of unmerciful severity in 1964. A year later, Lozano’s painting became increasingly abstract and minimalist. Now, space and motion played important roles. One of the highlights of the artist’s painting career is the Wave Series, produced between 1967 and 1970, in which she conceptualized painting. Parallel to this, beginning in 1968/69 she also commenced work on conceptual, performative investigations, which she referred to as Language Pieces. Here, she advanced the “dematerialization”3 of her art, shifting away from the art object and painting to works based on ideas.

During this period, Lozano was well-connected within the New York scene. Her friends included Carl Andre, Hollis Frampton, Robert Smithson, Stephen Kaltenbach, and Dan Graham. In the early sixties, her work was shown at Richard Bellamy’s Green Gallery, the most important avant-garde gallery in New York, which featured a new generation of artists who had turned away from Abstract Expressionism: Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Dan Flavin, Lee Lozano, Claes Oldenburg, Tom Wesselmann, James Rosenquist, George Segal, Yayoi Kusama, and Mark di Suvero among them.4 Lozano had taken part in numerous group exhibitions, and had had solo shows at the Bianchini Gallery in 1966 and at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1970/71. By 1968, the German gallerist Rolf Ricke had begun promoting her work in Europe with great enthusiasm. At the pinnacle of her artistic success, about a year after her solo exhibition at the Whitney, where her Wave Series and the conceptual Language Pieces were shown, she staged her exit from the New York art scene as Dropout Piece (ill. p. 43, bottom). In August 1971 she had begun boycotting women (see ill. p. 195). Originally planned as a temporary, experimental project, this, together with her withdrawal at the age of forty-one, elicited much speculation.5 These radical measures most certainly contributed to the fact that her work as a whole was quickly forgotten.

I became aware of Lee Lozano in 2005, and my encounter with her oeuvre left a lasting impression on me. Along with their courage and strength, I was extremely fascinated by the energy and power that emanated from her works. I liked the resoluteness of her stroke. The latent rage inherent in many of her works caused me to become pensive, and I was enthralled with the way she intelligently, keenly, and wittily dealt with conventions and entrenched modes of thought.

The radicalism and stubbornness of Lozano’s work—the way she, for example, undermined stereotypical images of femininity and masculinity—as well as its subtle aggression, crudity, and directness, frequently paired with sarcastic humor, make it seem eerily contemporary. Added to this are its investigative character as well as Lozano’s ambition to combine art with life. I wanted to make this artist’s work accessible to the public in all its complexity in an exhibition and accompanying catalogue. This first all-embracing retrospective of Lozano’s oeuvre in Scandinavia comprises nearly two hundred works—including 55 paintings, 127 drawings, and 11 of her conceptual Language Pieces—and will now bring the rich diversity of her art to the attention of a wider audience.

Growing interest in Lozano’s art and her discovery—or rather her gradual rediscovery—in Europe have only recently led to a number of exhibitions, including shows at the Kunsthalle in Vienna in 2004, which mainly featured her early works, and at the Kunsthalle in Basel in 2005, which presented an overview of her artistic career. A number of her paintings were also shown at documenta 12 in 2007.6 The important rediscovery of her art is forcing a rethinking and reworking of the established art-historical canon of the sixties and early seventies. I would like to thank Lucy R. Lippard, Jo Applin, and Benjamin Meyer-Krahmer for their zeal in delving into Lozano’s oeuvre in their essays for this catalogue. Special thanks go to Barry Rosen and Jaap van Liere of the Lozano Estate for having so generously supported this project, not only with their extensive knowledge of Lozano’s art but also with their wholehearted enthusiasm for it.

Early Works and Arrival in New York

Even in Lee Lozano’s early still lifes—painted in 1960 probably while she was still in Chicago—there is that same sense of nervous disquiet, menace, and unpredictability that also mark the works she produced during her initial years in New York. Here she is confronting the still-life tradition, but instead of the paintings being balanced meditations on death and impermanence, they occupy space and practically force themselves on us. In contrast to the artist’s anatomical studies from her days at the Art Institute, the expressive, driven brushstrokes, harsh palette, and impasto application of paint used to depict a grinning skull in one of the still lifes make it look almost shockingly alive (ill. p. 25, top). The dark eye sockets suck in the viewer’s gaze. The other still life deals with the unpredictability and uncertainty of life (ill. p. 25, bottom). In a Baroque manner, the sharp, glittering blade of the knife juts out over the edge of the table, leaving the scraped bone behind it, and is now directed diagonally at the viewer. After her arrival in New York, Lozano produced the “peculiar” painting No title (USA) in 1960 (ill. pp. 22–23). It features the eastern section of the United States, in the form of a green map, being shot out of the muzzle of a gun. The barrel of the distorted revolver resembles a torso or a headless body, the two auxiliary barrels suggesting arms held high—one arm ends in an orange, balled fist, while the other turns into a cannonball-shaped female breast with a pointed nipple. (A pencil drawing of a male torso with a grinning skull peeping out of the hole at the end the amputated left arm and a cigarette lighter sticking out of the neck where the head should be [ill. p. 27] may have served as the basis for this painting.) If it is turned counter-clockwise at a ninety-degree angle, the outline of America’s east coast resembles the head of a wolf; its eye is a somewhat lighter-colored green spot, placed exactly where New York City would be—the city in which Lozano was now living and working. It is a programmatic painting through which the artist, strong and ready for battle, announces her arrival. In 1961 Lozano moved into a downtown loft. In rapid succession, she created a series of studio drawings, quickly propelled onto paper with sure, powerful strokes. These images are strewn with isolated, severed body parts: mouths in wide-open grins, teeth, erect penises, and breasts appear again and again in different kinds of groupings. Space in these pictures is sometimes claustrophobically convoluted, pervaded by pipes and drains, electric sockets, nuts, traffic lights, and fuse boxes (ill. pp. 12–13). Occasionally, she integrates a window perspective, as she does in No title (1961, ill. pp. 28–29), in which a motorcyclist and a green-and-red traffic light appear in the interior space. These drawings, which are practically devoid of people, depict a grotesque, nightmarish, fragmented world and must surely reflect Lozano’s initial sense of foreignness in the unfamiliar metropolis of New York.

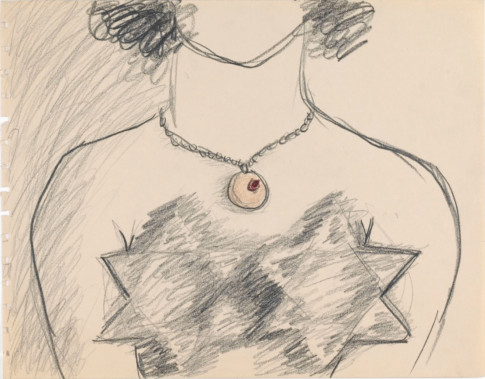

Out of her descriptions of an apparently dissociated world, Lozano gradually crystallized the recurring elements of her very own pictorial language, which she frequently employed in collage drawings (for example, ills. pp. 4–5, 8–9, 11). Besides the elements mentioned above, she adds black holes, black suns, blue crescent moons, moustaches, telephones, tongs, drills, tubes of paint, knives, and Stars of David, as well as other colorful stars. In 1961 she assembled parts of this vocabulary into a booklet. She also created a series of sketches that deal with the interaction among individuals within various societal structures. These energy diagrams investigate and analyze the different states and social situations experienced by the individual while interacting with others—such as, for instance, dependence, identity, independence, conversation, sex, social situation, and affection (see ill. p. 30). Lozano integrated these experiences, which she had translated into schematic diagrams, into her early drawings.

Airplane Series

In circa 1962, airplanes began whizzing around in Lozano’s surrealist imagery. They fly into ears and out of mouths, circuit heads, or hover over an erect penis as if above a launching pad. A few of the planes have carefully drawn, male sex organs dangling from their fuselages. In one painting, an enormous penis shape has been cut out of a landscape, revealing a blue background (ill. p. 33)—is it the sky or water? An airplane is flying or perhaps swimming within it like a gigantic sperm. More shapes, resembling severed body parts, appear in other paintings, spreading out into infinity, often before a blue background. A red plane, for instance, flies into an ear floating in space which is being circled by a different, yellow airplane (ill. p. 53). The wing of another one is being clutched by a huge, grotesque hand that appears out of nowhere and is ornamented with a shark-like mouth (ill. p. 56). In another drawing, airplanes buzz around like swarms of flies (ill. p. 60). What are these strange creatures about?

I would like to propose that they be regarded as a continuation of Lozano’s investigative working practice. It seems to me that they are metaphors for a kind of thought energy—for ideas circulating, being heard and taken in, processed, produced, and sent out again. One could regard these airplane pictures as investigations of the raw material necessary for every sort of creative activity. After all, everything starts with an idea, including art. Lozano puts it this way: “Ideas are the most powerful thing in the world” (see ill. p. 235, top). Lozano carried on her intense exploration of the subject of creativity as energy. As can be seen from the sperm-shaped airplanes, in her art this energy seems to be of the masculine kind, and this becomes even more obvious later. It certainly has a bearing on the artist’s visual worlds, which were permeated by phalli until around 1964, even though, at first glance, one might get the impression that her work was dominated by sexuality or sex.7 Lozano’s gallerist in Cologne, Rolf Ricke, in a way confirmed this when he told me that in conversations with him, Lozano stressed that she regarded creativity as male energy.8 Her phallocratic or phallic imagery stands in the tradition of Salvador Dalí and the other Surrealists, anticipating the absurd, perverse worlds of artists such as Paul McCarthy. During those years, phalli emerged out of Lozano’s pictures everywhere. They shoot out of human palms, like mushrooms; or, placed in the faces of grotesque figures, they mutate into telescopes through which the world is seen. They also become nightcaps, dangling down annoyingly in front of a face; or they are opaque blindfolds that block sight (ills. pp. 76, top; 88–89; 92, top right; 93). Penises bring light into the darkness or carry out power struggles, as is the case in the drawing Two Men, in which the thumb and the little finger are phalli, with the former dominating the latter (ills. pp. 86; 76, bottom). Yet closer inspection shows that this is not about sexuality, and definitely not about eroticism; rather, it is probably about strength, capability, skill, and as-yet-unrealized potential—in other words, about potency in the truest sense of the word. This force is ubiquitous; it permeates and transforms everything, like the penises in Lozano’s endless metamorphoses (ills. pp. 97–97, 98). With sarcasm and a good dose of humor, Lozano has the phalli penetrate all kinds of slits and openings (ills. pp. 95, 99). Time and again, however, she made the downside of potency visible. When it is achieved, it often reverses itself and becomes a restricting force and is expressed as power and dominance, which was characteristic of the patriarchal society in which she lived.

Women who appear in the artist’s work have no faces and are usually represented by breasts or the bottom half of a torso (ill. p. 77). For Lozano, the vagina is also no longer the origin of the world, as it is in Gustave Courbet’s famous painting L’Origine du monde from 1866, to which she makes reference. Instead, it is a vending machine into which a hand wearing a blue glove is about to insert a coin—a quarter, to be precise—on which can be read the word “Liberty” (ill. p. 75). In the consumer world, everything becomes a commodity; not only the vagina, but also “freedom” can supposedly be bought. Lozano kept her distance from all kinds of groups. As an artist, the nascent women’s movement did not attract her either. An entry in one of her notebooks reads, “I am not a feminist. I speak to both men and women because I think both men and women are slaves in today’s society.”9

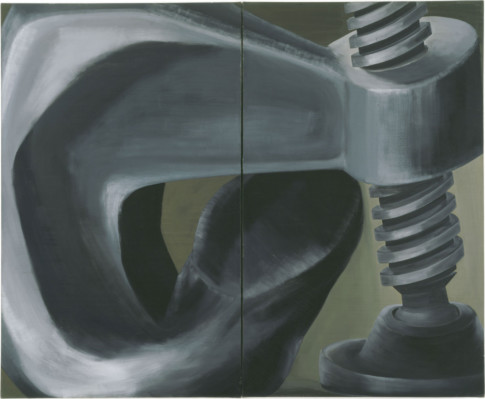

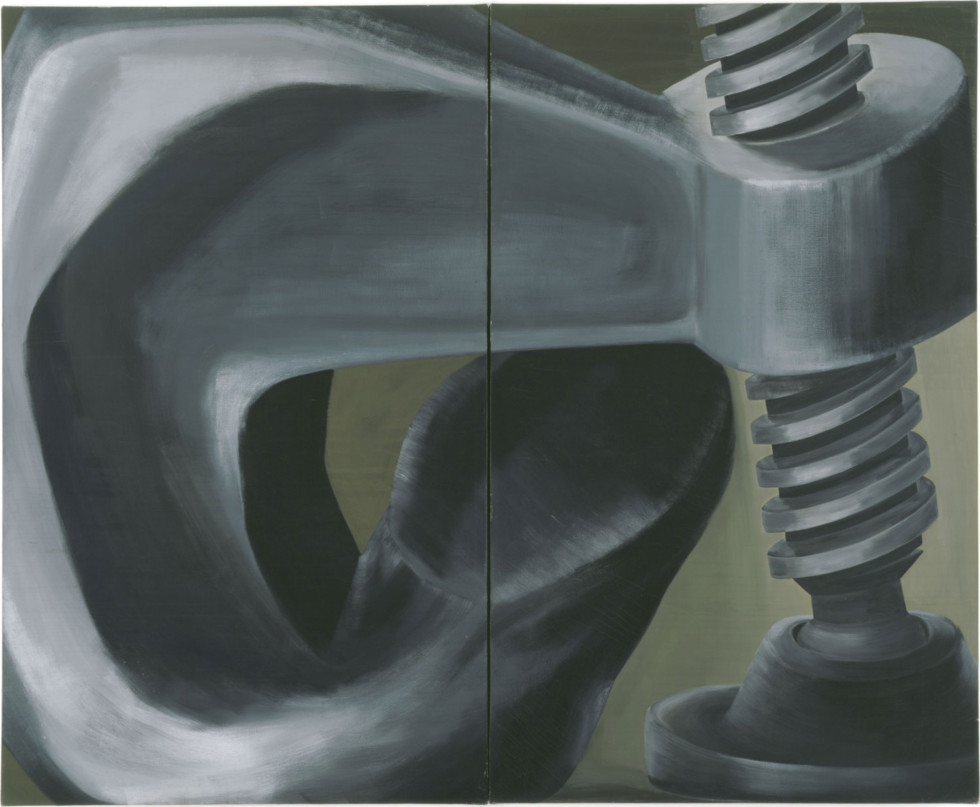

Tools

Starting in 1963, Lozano commenced painting tools. Even children are often fascinated by them; they represent a world of possibilities. Tools are used to build the world. Lozano alludes to their common association with male potency in one of her drawings (ill. p. 131, right). The formats of these paintings are enormous: up to six meters long, they often consist of two or even three panels. Producing them required the artist’s total physical commitment. To the viewer, these gigantic pictures are overwhelming, fascinating, and at the same time frightening. They are sarcastic commentaries on the male-dominated world in which Lozano tried to assert herself as an artist.

While the early tool paintings are still very painterly, Lozano’s style changed direction, moving toward Hard Edge and Superrealism; the works became increasingly monochromatic, such as the picture of the huge, penis-like bolt from 1964 (ill. pp. 136–137). Winding around and into each other, the anthropomorphic, oversized tools are giants conveying a sense of aggression and violence. In Peel and Ream, this impression is intensified by a suggestion of movement (ills. pp. 138–139, 128–129). The artist created hundreds of studies and sketches for this group of paintings, some of them very small, realistically depicting screws, the tips of nails, and sections of drills. They demonstrate how meticulously she prepared her compositions.

While, as far as we know, Lozano did not exhibit her early figurative works, it was the tool paintings, the ensuing minimalist works, and her conceptual pieces for which she became known. The tool paintings were shown at the Green Gallery and at her first solo exhibition at Bianchini in 1966. It is questionable, however, if the subversive dimension of these works was recognized at the time.

Abstract Paintings

From 1965 onwards, Lozano moved toward abstraction in her paintings. Her directed application of paint causes these abstract images to attain a haptic quality, oscillating between the impression of spatiality and planarity, three-dimensionality and two-dimensionality. The artist has geometric and stereometric shapes, such as triangles and cones, meet or collide in the painting’s space, which seems to have expanded to become a macrocosm. The element of movement, clashing forces, and violence continue to resonate, but are now extended into the universe. Lozano aimed at subverting color as the mover of emotion, and reflected on how she could make “energy paintings.”10 She also prepared numerous drawings and preliminary sketches, many of them very small, for this group of paintings (all having verbs as titles, such as Pitch, Clash, Clamp, or Verge). She not only noted which compositions she felt were successful, but commented on studies she thought were not good, boring, and so forth (ills. pp. 150, 151). Lee Lozano is the kind of painter who masters her métier down to the last detail, investigating every possibility painting has to offer here. She applies several layers of paint using a three-inch standard household paint brush, the top layer so dry that the surface looks like wet, combed hair. Depending on the incidence of light, the surface creates different optical effects as well as a feeling of accelerated motion and energy (ills. pp. 142, 143, 155).

Her notebooks also exude the artist’s interest in different energy phenomena: “The energy which emanates from the forever conflict in painting between the second dimension of its object-space and the third dimension of its implied space, or from the forever contradiction in painting between its static solid-matter surface and the passages of movement and time it evokes in the mind,” she writes.11 Rolf Ricke, who worked with her from 1968 to 1971, recalled that “In her studio, I saw many of her large abstract paintings, some of them with several parts; in these, she was working with energy, light, color . . . . But I never saw her earlier, more object-oriented works, which featured tools and sexual themes. Not once did I ever see them; not at Dick Bellamy’s and not at Paul Bianchini’s.”12

Wave Series

With her famous Wave Series, begun in 1967 and completed in 1970, Lozano continued her examinations of the theme of energy (ills. pp, 59–173). Here, the artist started conceptualizing her painting, first of all by establishing rules. The cycle consists of eleven abstract paintings of the same size (ninety-six by forty-two inches) that explore the phenomenon of waves. She articulated the concept for the series as follows: “The metaphor upon which the image of the paintings is based is that of the extended electromagnetic spectrum.” The waves take up the vertical axis of each painting. The number of waves per painting as well as their length are based on mathematical equations, the former derived from the even factors of 96 (2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 24, 32, 48, 96, with the exception of 192). The length of each wave is calculated using the quotients of the picture’s height divided by the number of waves: for 2 Wave, the length is forty-eight inches; twenty-four inches for 4 Wave; and so on. Another one of the production rules was that each painting had to be completed in one sitting—which meant that 2 Wave required eight hours, while 32 Wave was a performance of eighteen-and-a-half hours—“the longest to date. Although tedious, the painting went ‘smoothly’ & my coordination was excellent, maintained my energy to the end. Very stoned on hash throughout.”13 She worked for three days without interruption on 96 Wave. The length of the waves in 192 Wave is so short that they resemble a single, long line. This last painting of the series is incomplete and contains only the pencil drawing of the waves on the prepared canvas.

With the exception of four of them, the Wave Paintings are all monochromes. In order to achieve the matte, rich hues, and metallic shimmer, Lozano used iron oxide paint manufactured by Shiva. Using a standard three-inch household paint brush, she applies the paint to the canvas, which has been grounded with lead white, in a vertical motion following the waves, while the direction of the brush in the adjacent color fields to the right and to the left meet the waves horizontally. The effect of these paintings is dependent on both the viewer’s standpoint and the incidence angle of the light. Due to the surface structure, which looks as if it has been combed, the angle determines how the light is reflected. Lozano was reluctant to have the paintings offered for sale individually; she wanted them to be shown together at an important institution in the United States before possibly being sold. She felt that the pictures belonged together and that they should be installed as a series, as a total work of art (see Whitney press release on p. 51). Her idea was to have them installed in a room with black walls, which would absorb the light; they were intended to lean against the wall or be hung higher than usual. The only light in the room was to come from spotlights directed at the canvases. In her notebooks, Lozano also considered presenting the series against a golden background or photographs of the sky. She did not want the paintings to be framed, because that would prevent the impression of the waves spreading out vertically upward and downward beyond the boundaries of the canvas, creating a vibrating space comprised of light and energy. “I wanted to give people a fantasy of being in space. That was the idea originally to be like a science experience, from an artist’s view.”14

The End of Painting and the Beginning of the Conceptual Works

Big Circle (1969/70) was one of Lozano’s last paintings. This work, measuring six by six meters, was made up of four panels containing circular segments and was installed as a gigantic circle against a white background, with one canvas above, one below, one on the right, and one on the left (ill. p. 39). Also known as North South East West, it conveys a sense of light and infinite space. The imaginary center of the circle “may extend to a line in the future,” Lozano wrote on a preliminary study for the painting. Thus, the measurement of space is enhanced by the notion of time.

While she was still working on the Wave Series, Lozano began to think about how she might develop her painting and in which direction she might proceed as an artist. In September 1968 she noted, “I wish to find the kind of work that will most engage my attention. Whether it is painting, some other art or something else entirely I do not know.”15 In May 1969 she added, “I found it! My new ‘Life-Art’ Pieces.”16 She considered, “Why not impose form on one’s life the way one makes art? At least it is worth an experiment, and I’m starting now.”17 In February 1969 she began creating conceptual, text-based, performative works. These so-called Language Pieces are investigations shaped by self-imposed rules that always begin and end at some point in time. In these “Life-Art Pieces,” art and life meld. Since these intangible investigations could not be easily exhibited or sold, they radically circumvented the commodification of art. Hence, in General Strike Piece (“started Feb 8, 69 in process at least through summer ‘69”), Lozano began her gradual retreat from New York’s art world for the purpose of achieving what she called a “total personal & public revolution.” She was not the only one who took up a resistant stance toward the growing treatment of art as a commodity; this was actually the basis of the growing Conceptual Art scene in the late sixties. Lozano’s protest, however, went even further. Instead of expanding her ego as an artist, as required by the system, she set herself the task of dismantling it and of “sharing” instead of competing for influence. She only wanted to exhibit works whose aim it was to share ideas and information about a “personal & public revolution.” For her General Strike Piece, she compiled a list of her last visits to New York exhibitions, museums, film screenings, bars, and other places, along with the dates (ill. p. 203).

Lozano began writing down her considerations with respect to how the power of the art market, the galleries, and the art dealers could be broken as early as the fall of 1968. She also believed that artists should no longer “entertain” collectors, but that it should be the other way around: “Boycott galleries & dealers too. Collectors chosen by artist as ‘allowed to buy’ strictly on basis of how interesting they are when they visit artist. Collectors as entertainment for artists. Price of art fixed . . . .”18 For the Grass Piece (April 1–May 3, 1969) she decided to get high every day and then wait and see what would happen, while in the ensuing No-Grass Piece (May 4–June 6, 1969), she observed her reactions over the same period of time without marijuana (ills. pp. 205, 206–207). She noted, “Seek the extremes. That’s where all the action is.” In her Masturbation Investigation (April 3–5, 1969) she explored different kinds of stimulating one’s own genitals (ill. p. 208). In Real Money Piece (April 4–July 9, 1969) she offered guests in her studio “coffee, diet Pepsi, Bourbon, glass of half and half, ice water . . . and money like candy.” She noted the reactions of her visitors, which ranged from refusal to indignation, embarrassment, and acceptance of cash (ill. pp. 211–213). As mentioned above, Lozano started recording her ideas and thoughts in notebooks in early 1968. “I have started to document everything because I cannot give up my love of ideas.”19 She shifted her focus from the production of art objects to idea-based works, henceforth conceptualizing almost all of her activities in the journals. These conceptual works consist mainly of self-imposed rules that increasingly structured her life. As of 1969, many of these investigations were being conducted simultaneously. The transcripts of her pieces, to be exhibited or sent to friends, were called “write-ups,” which she regarded as drawings. An entry in one of her notebooks reads “Continue with the idea of making the write-ups more & more like drawings.”20 Not all of these ideas, however, were developed into write-ups. During this period, the artist maintained a brisk exchange of ideas with Dan Graham and Stephen Kaltenbach, and her radical, word-based, performative works made her one of the pioneers of Conceptual Art in New York of these years. Kaltenbach described her as “one of the three most intelligent artists” he knew in the city.21 Lozano began the Dialogue Piece (April 21–December 18, 1969) as compensation for the increasing isolation resulting from her self-imposed rules. She invited various people from the art scene to converse with her in her studio (including Claes Oldenburg, Brice Marden, Robert Morris, Dan Graham, Larry Weiner, Robert Smithson, Marcia Tucker, Keith Sonnier, Stephen Kaltenbach, and Dick Bellamy). She kept a record of their names and when and where the conversations took place (see ills. pp. 214–221, 236). The content of the conversations, however, remained confidential: what mattered was that an exchange took place. This nullified the traditional relationship between the artist as transmitter and the viewer as receiver. In dialogue, both became equal participants, and the energy flowed in both directions. Another important aspect in this respect is that Lozano kept her ego in check instead of reinforcing it, as was usually the case in the art world. She was interested in sharing, not in asserting herself.

Lozano described her experiences in the Dialogue Piece. “The Dialogue Piece comes closest so far to an ideal I have of a kind of art that would never cease returning feedback to me or to others, which continually refreshes itself with new information, which approaches an ideal merger of form and content, which can never be ‘finished,’ which can never run out of material, which doesn’t involve ‘the artist & the observer’ but makes both participants artist & observer simultaneously, which is not for sale, which is democratic, which is not difficult to make, which is inexpensive to make, which can never be completely understood, parts of which will always remain mysterious & unknown, which is unpredictable & predictable at the same time, in fact, this piece approaches having everything I enjoy or seek abt art, and it cannot be put in a gallery, although some aspects of it could be ‘exhibited’ if so desired . . .”22 She continues, “What if I stopped doing different Pieces & just did the Dialogue Piece for the rest of my life as my ‘work’? I could move to an exotic place & do it there; it has no space or time boundaries.”23 In 1970, before Lozano finally gave up painting altogether, she conceptualized in retrospect a series of her abstract, minimalist paintings, such as Punch, Peek and Feel (1967–70), Big Circle (1969/70), No title (1970), and Stroke (1967–70) by perforating the canvases (ills. pp. 37, 39, 180–181, 182–183). The placement of the holes is based on detailed sketches and designs made with the aid of mathematical calculations (see ills. pp. 184–187). Lozano does not perform gestural cuts, as Lucio Fontana had been doing since the early fifties in his Concetti spaziali, cutting open the canvases with a knife. There is a preliminary draft for Punch, Peek and Feel, for which she used a photograph of the painted canvas before perforating it, that features twenty-four round holes (ill. p. 36, bottom). The chads are attached to the photo with a thread. Just like the photographic study, the painting—which was given its title after the perforation—has twenty-four holes, but in this case, the chads have not been integrated into the canvas. The act of perforation brutally bursts the painting’s carefully constructed illusion of volume and space like a soap bubble. The holes allow seeing the stretcher frame and the space behind it, intensified by the shadows they create. On November 9, 1970, Lozano noted on a drawing, “The painting trip gets weaker & weaker, more & and more forced and distasteful” (see ill. p. 38). The artist felt that there was no way to return to painting without repeating herself. She was no longer interested in producing art objects. Instead, she proceeded with the “dematerialization” of her art.

In 1970/71, Lozano showed her Wave Series and Language Pieces in a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. She also lectured, for instance, at the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design in Halifax, Canada, and at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island, where she was advertised as a “conceptual artist working at transforming her life” (see ill. p. 238). Her boycott of women, which began in the first week of August 1971, was yet another investigation that Lozano set up as an experiment. This piece was originally supposed to terminate at the end of September 1971, and it was bound to the hope that it would improve communication between her and other women (see ill. p. 195). With few exceptions, however, Lozano continued her boycott, as far as was possible, until the end of her life. How could her art continue to develop from this point on? In her workshop in Halifax she talked about the expectations society placed on artists. “Everyone knows that an artist’s best work often covers a short period of time. . . . It’s almost very rare that an artist does high-quality work and maintains this great period throughout their career. Yet, it’s expected of him.”24 She also spoke of an appalling amount of competition and rivalry among her counterparts. Disillusioned by the art market and the New York art scene, Lozano ultimately decided to turn her back on this environment after “a decade of competitiveness.” With her Dropout Piece—which was, according to her, her most difficult—she left New York in 1972, at the height of her success as an artist. She edited her notebooks prior to her departure. Lozano was not at all alone, however, in making a radical break. In 1970, her friend Stephen Kaltenbach decided “to do a big conceptual piece: a life size art action. I decided to leave New York and the feeding frenzy of conceptual art shows that were happening in museums around the world.”25 He wanted to turn his life into a mystery for art historians to solve, and thought that the art world would try to find out what had happened to him. This, however, took thirty-four years to transpire. Lee Bontecou abandoned New York as well and did not generate any art for many years. Agnes Martin left the city in 1967 to move to New Mexico. Between 1967 and 1974 ceased painting altogether. Another example is the German artist Charlotte Posenenske, whose work has only recently been rediscovered. She stopped producing art in 1968 to take up her study of sociology, because she could not reconcile herself to the notion that art was unable to contribute anything to the solution of urgent social problems.26 Lozano’s Dropout Piece and the act of leaving the New York scene did not necessarily mean that she was no longer an artist from that point on. “I will renounce the artist’s ego, the supreme test without which battle a human could not become ‘of knowledge.’ I will not seek fame, publicity or suckcess,” she wrote in September 1971 (see ill. p. 46). She so radically conducted her artistic investigations that ultimately, nothing else seemed to be left.

Her complete withdrawal can be seen as a fundamental act of liberation: it was in this way that Lozano escaped the domination of the art market and the rules governing the individual within the context of society. From then on, the self-imposed rules of her conceptual works governed her contact with other people. Ultimately, the uncompromising attitude characteristic of her work and her personality led to Lozano’s art taking place primarily in her own mind, so that it was hardly accessible to others. After she decided to abandon the New York art scene, she told her gallerist Rolf Ricke at their last meeting that she had changed her name and would henceforth go by the name “Lee Free.” Later, she shortened it even more, to “E,” as in “energy.”

In 1998, the Wadsworth Atheneum exhibited Lozano’s Wave Series and Language Pieces. The artist consented to the show, yet she was not interested in viewing the installation. In the year before her death, she created one last Language Piece: a questionnaire that she sent to her gallerists Barry Rosen and Jaap van Liere. Questionnaire, With Jokes, Concerning Purchases & Purchasers of My Art, “dat. August, September, October 1998,” was signed “E.” Like a bookkeeper closing the books and trying to assemble a final overview, the questions inquired into, among other things, how old the buyers were, what their nationalities were, what kind of education and professions they had—if they were they businesspeople, academics, politicians, scientists, artists, or simply wealthy. Lozano was interested in the buyers’ genders and in knowing what percentage of those who were male were homosexual. At the same time, she wanted to know where the acquisition would be kept: at home, at a museum, or in an office. The questionnaire remained unanswered. Lee Lozano, “E,” died in 1999. In accordance with her last will, she was buried in an unmarked grave. The subversive power and radicalism in her attitude toward art, society, and life have retained their explosive force to this day.