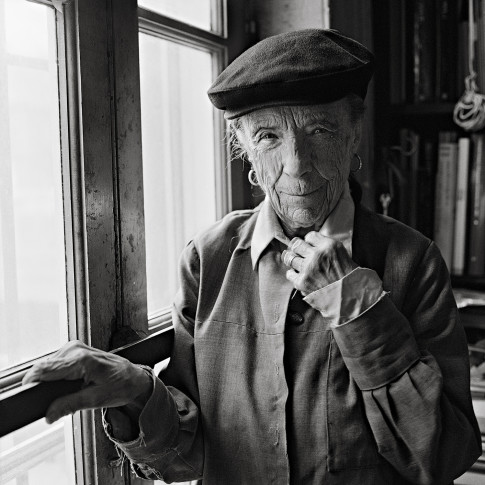

Installlation view, Louise Bourgeois - I Have Been to Hell and Back, Moderna Museet, 2015 © The Easton Foundation/BUS 2015. Photo: Åsa Lundén/Moderna Museet Bildupphovsrätt

The nine exhibition rooms

She is best known for her monumental spider sculpture Maman (1999), which has been exhibited all over the world. For Bourgeois, the spider was a creature with positive connotations, and in her mind it was linked to her mother. Both of them worked with mending and weaving, and both were tidy and patient. The spider can also be seen as the artist herself, creating with her own inner material. Measuring nine metres tall, Maman now stands outside the museum entrance, as a guardian of the exhibition. I Have Been to Hell and Back presents 103 works, spanning Bourgeois’s entire career. Some 30 of these are shown here for the first time in public. The nine exhibition rooms reflect how different themes evolved and developed in her practice over the years.

Runaway girl

Louise Bourgeois studied art in Paris in the 1930s. Her teachers included André Lhote and Fernand Léger. She also worked as a guide at the Louvre, became familiar with surrealist art and started her own gallery. It was at this gallery that she met her future husband, the American art historian Robert Goldwater (1907–1973). In 1938, the couple moved to New York, where they shortly after had three children.

The first exhibition room focuses on the move from France and covers Bourgeois’s explorations of the roles she had to assume in her new country. The images are characteristically unstable and searching. The print Femme Maison (1947, printed in 1990), which translates as Housewife, shows a woman with her upper body hidden or replaced by a house. She looks like she wants to hide and seems unaware that she is half-naked. Take Me Right Back to the Track Jack (1946) presents a figure with several arms and legs that appears unable to choose which direction to go. The print series He Disappeared into Complete Silence (1947) is Bourgeois’s first attempt combining image and text in a poetic and surrealist way.

Loneliness

From the mid-1940s, Bourgeois devoted herself mainly to sculpture. When the family moved to a building where the roof could be used as a temporary studio, she was able to work in larger formats. The slim, totem-like sculptures in this room are part of the Personages series. Bourgeois regarded them as mementos of the friends and acquaintances she had left behind in Paris, in a time of impending war. The first versions were carved in wood and painted. Later, she had them cast in bronze, and she has also revisited the motif in textile materials. Personages was presented from the very beginning as individuals in various constellations, directly on the floor without bases. In this way, the exhibition room is transformed into a psychological space charged with presence.

The surrealist fascination for primitivism and ritual is prominent in these works. Bourgeois may also have been inspired by her husband Robert Goldwater’s research into how modern painting had been influenced by primitivism. All the sculptures in this series share a sense of loneliness. Even Knife Couple (1949), with two figures sharing a small space, suggests conflict and tension rather than togetherness.

Trauma

Trauma features works focusing on experiences from the darker sides of life, such as events that cause feelings of confusion and helplessness. In these works, secrets are brought out into the light – things that are too complex for words or so bewildering that they are traumatic.

Many of Louise Bourgeois’s works relate to childhood memories, events that were perhaps unfathomable when they occurred but played a decisive role later on. She constantly re-explored the betrayal she felt when her father’s affair with the family’s English tutor was exposed. Perhaps this trauma is what forms the core of Couple (1996), where two elegantly dressed figures tumble around in a literally headless passionate embrace. Janus Fleuri (1968) is one of several works on the same theme. Here, two sets of male genitalia appear to have fused, pointing in opposite directions, like the faces of Janus. The seam where they are joined resembles a vagina. Their indeterminate and fleshy physicality is at once both alluring and repulsive.

Fragility

The works in this room focus on the fragility of body and mind. Using a red marker, Bourgeois traces her way back to memories of when her children were small. In the drawing Le Père et Les 3 Fils (1998), the large chair represents the protective father, under which the three children seek safety and tenderness. Le Défi (1994) is a trolley with shelves stacked with fragile glass objects from Bourgeois’s own home. Most of them belong to the traditional female sphere (mirrors, perfume bottles, vases, decanters). These glass pieces symbolise memories that can appear both unreal and exquisite through the filter of time.

Natur Studies

The Nature Studies theme relates to the connection between nature and the human body in Bourgeois’s oeuvre. In Torso, Self Portrait (1963–64) the body is reduced to a few shapes – breasts, ribs, spine – suggesting a fossil or a protective armour.

In the 1960s, Bourgeois began experimenting with the specific characteristics of different materials. Avenza (1968–69) was originally made of plaster and later cast in latex, bronze and plastic. It represents a physical landscape, with hills and cavities. Bulging shapes feature frequently in her sculptures, alternately as representations of female breasts and male genitalia. Some suggest uncontrolled cellular division and pathological mutations, while others appear to represent the indefatigable exuberance of life.

Eternal movement

Perpetual motion that spreads infinitely is a recurring theme in Bourgeois’s body of work. Together, the large prints with graphite and watercolour from the series À L’infini (2008) form a flow of tracks. The repetition of lines across the paper is like blood pulsating through arteries, or a shuttle passing back and forth in a loom. The near-hypnotic rhythm is like an incantation or consolation. The red colour – which usually signifies aggression and conflict in Bourgeois’s art – also suggests a compulsive tendency.

In Arch of Hysteria (1993) she explores a subject referring to the 19th-century neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot’s (1825–1893) research on hysteria. The word itself comes from the Greek word for womb. Hysteria was considered to be a specifically female complaint, but according to Bourgeois the hysteric could just as well be a man. Despite being critical of Charcot’s opinions about women and his dubious methods, she admired his observations of the link between physical and mental states. The male body in Arch of Hysteria oscillates between being extremely tense and totally relaxed. It resembles an acrobat, a dancer or a yogi in its complete vulnerability and defencelessness.

Relationships

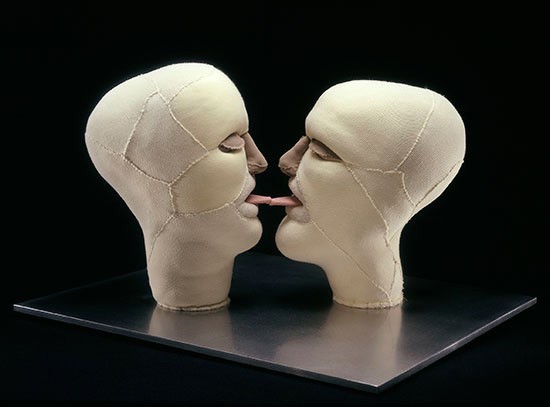

Bourgeois was fascinated by how people relate to themselves and others. Relationships presents works reflecting everything from love and togetherness to pain and separation. From the 1990s, she made soft sculptures out of fabric and clothes that she had collected over the years. In Together (2005) two individuals attempt to make contact by letting their tongues touch.

Taking and giving

The alternation between giving and taking in human relations was an aspect that particularly interested Bourgeois. 10 AM Is When You Come to Me (2006) is a series of pictures of hands. For 30 years, Bourgeois worked with her assistant Jerry Gorovoy, who came to her studio nearly every day at 10 in the morning. Over time, she relied increasingly on his presence in order to create. In these drawings we see hands that meet and interact. The pictures express her gratitude but also the concerns she had about being dependent on another person for her ability to work. Who created day and night? Where are we going? In The Five Magic Words (2002) Bourgeois addresses life’s crucial questions with such candour and simplicity that it offsets any banality.

Balance

In the last room, there are works relating to balance and redemption. Here we find one of Bourgeois’s so-called cells, a room-like installation where a woman is sitting absorbed in herself, surrounded by five columns, with a blue sphere in her lap. She appears to be in harmony. In the final work, Untitled (I Have Been to Hell and Back) (1996), a handkerchief is embroidered with words that seem to express the quintessence of both her oeuvre and this exhibition: “I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful”.