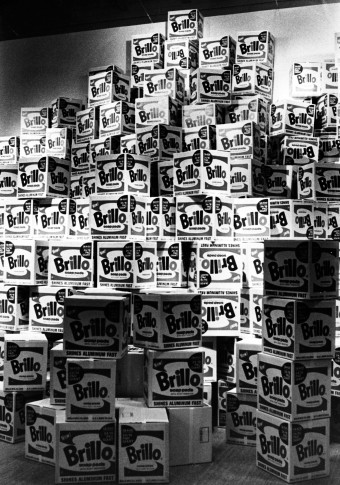

Andy Warhol, The Chelsea Girls, 1966 © 2012 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / ARS, New York / Bildupphovsrätt 2012

On films 1963–1968

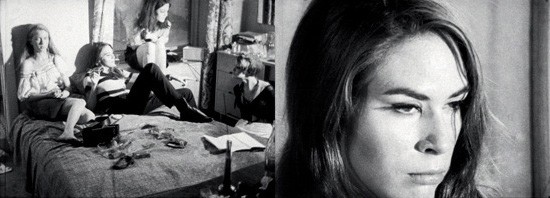

The Chelsea Girls, 1966

Double screen, b&w, color, silent, sound, 24 fps, 3 hrs 24 mins

Brigid Polk (Berlin), Susan Bottomly, Ari Boulogne, Angelina Davis, Eric Emerson, Patrick Fleming, Ed Hood, Gerard Malanga, Marie Menken, Mario Montez, Nico, Ondine, Ronna Page, Rene Ricard, Ingrid Superstar, Mary Woronov

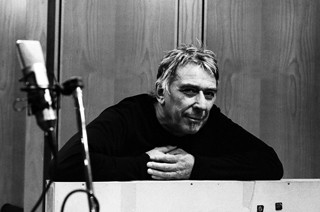

The Chelsea Girls, Warhol’s most renowned and first commercially successful underground movie, combines his experimentation with multiple formats and the intimate depiction of Factory superstars. The film is a visually complex and forthright portrayal of these troubled souls. Made up of 12 unedited black-and-white and color reels, each 33 minutes long, which are projected in pairs, the unconnected and individually titled episodes unfold in different rooms of the famed Chelsea Hotel and in other locations around town. Mostly improvised, except for two ‘Hanoi Hannah’ episodes written by Ronald Tavel, the film features an amphetamine-doped Ondine as the Pope listening to confessions, Eric Emerson holding an intimate monologue before doing a striptease, and Nico silently weeping while lovely patterns of light play across her face.

All my films are artificial, but then everything is sort of artificial”

Blow Job

1964, b&w, silent, 16 fps, 41 mins

DeVerne Bookwalter

The viewer of Blow Job sees a close-up of the head of a handsome man leaning against a brick wall. Apparently the young man is waiting for the titular act. A bright light from above illuminates the set, creating vivid shadows on the man’s face that alter when he moves. What the three-minute reels chronicle for the next 36 minutes, at an exasperatingly slow pace, is what the viewer imagines to be a sexual act, complete from start to finish. But only from changing facial expressions can one assume that fellatio is being performed by an off-screen presence. The duration of the act leaves the mesmerized viewer plenty of time to study the filmed countenance, which reveals a multitude of emotions ranging from ennui and pleasure to sexual gratification and alleviation. Despite its suggestive dingy title, Blow Job refuses to convey an unambiguous message of authenticity. The act exists for itself; the fantasized off-screen presence fills the void with eroticism.

Empire

1964, b&w, silent, 16 fps, 8 hrs 5 mins

Certainly Warhol‘s most infamous film, Empire consists of a stationary shot of the iconic Empire State Building, recorded from the offices of the Rockefeller Foundation on the 41st floor of the Time-Life Building. Filmed from 8:06 p.m. to 2:42 a.m. on July 25-26 and later projected at 16 frames per second, thus stretching the duration to about eight hours, the film presents the landmark building as a superstar. With the setting of the sun, the static composition gives way to a drama that derives solely from light patterns. Floodlights on the exterior of the building come on, and lights flicker on and off every ten minutes. At the beginning of reel 7, a reflection of Warhol appears in the window. The floodlights finally go off again, leaving the frame in almost complete darkness. Despite the film’s minimalist concept, Empire‘s intense material imagery gives rise to an infinite realm of interpretations.

Sleep

1963, b&w, silent, 16 fps, 5 hrs 21 mins

John Giorno

In Sleep, Warhol‘s first film, he allowed his Bolex camera to gaze stoically at the naked body of his sleeping boyfriend, the poet John Giorno. Over a period of several weeks Warhol kept returning to his sleeping subject, shooting hundreds of three-minute reels. He edited the footage to create a complex montage of different takes and angles with shots looped and repeated. The stroke of brilliance in Sleep and in Warhol’s other early silent films was to film them at 24 frames per second but to project them at 16 frames per second, a technique that had the effect of slowing down movement and further stretching time to give the projected image an ethereal quality.

Kitchen

1965, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 66 mins

Electrah, Donald Lyons, David McCabe, Rene Ricard, Edie Sedgwick, Roger Trudeau

The cramped, wholly white kitchen in Bud Wirtschafter’s loft is the stage for Warhol’s new superstar Edie Sedgwick, who appears in the first reel alongside Roger Trudeau. The two play an unhappy couple. Their conversation is interrupted continually by their search for a hidden script or by Sedgwick sneezing and signaling to someone behind the camera to whisper her the lines of Ronald Tavel‘s scenario. In the background, Rene Ricard is washing dishes for most of the film. In the second reel Donald Lyons and Electrah join the tedious conversation, and at one point David McCabe comes in to snap some photos. The acting out of the scenario finishes before the second reel runs out, encouraging other Factory members to walk on set. It’s up to the viewer of Kitchen to decide whether he is witnessing a disastrous disintegration of a production or something thoroughly scripted and totally intentional.

Tarzan and Jane Regained… Sort Of

1963, b&w, color, sound, 24 fps, 81 mins

Wally Berman, Dennis Hopper, Naomi Levine, Taylor Mead, Claes and Pat Oldenburg, Andy Warhol

During a two-week sojourn in Los Angeles, Warhol used his newly bought camera to shoot his first partially scripted feature, a playful take on Hollywood adventure movies. Tarzan, played by underground star Taylor Mead, is seen in a series of loosely connected episodes. He exercises on Venice Beach, bathes with a completely naked Jane – actress Naomi Levine – in a bathtub at the Beverly Hills Hotel, and later has to rescue her. Meanwhile, he meets artist Claes Oldenburg and has a manhood contest with Dennis Hopper. In one scene Tarzan even gets spanked on the bare buttocks by Warhol, after refusing to climb a palm tree. Warhol’s camera style, much like that of a home movie, and the actor’s hyperbolic performance already allude to Warhol’s later ironic takes on Hollywood genre movies.

Haircut (No. 1)

1963, b&w, silent, 16 fps, 27 mins

John Daley, Freddy Herko, Billy Name (Linich), James Waring

Set in a spacious loft, each of the six reels of Haircut (No. 1) is filmed from a different camera angle and features meticulously designed, theatrical lighting by Billy Name. A stark contrast between the tight close-ups and the depth of field in the vast, shadowy loft gives the images an almost expressionistic look. After an introductory reel, in which the setting is framed and a shirtless Freddy Herko poses for the camera, Billy Name is shown diligently giving John Daley a trim. Drawing attention away from the linear activity is the half-naked Herko, who performs for the camera in the role of a provocatively sexed-up, homoerotic faun. On the last reel, choreographer John Waring joins the scene, and – with a sudden and startling close-up of all four men glancing back at the camera and rubbing their eyes – the film ends.

Henry Geldzahler

1964, b&w, silent, 16 fps, 99 mins

Henry Geldzahler

Only one day after finishing the filming of Empire, Warhol used the rented Auricon camera and the leftover film to make a 99-minute portrait of Henry Geldzahler, then curator of contemporary art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and a friend of the artist. Geldzahler‘s cinematic portrait is one long silent shot. He sits on the Factory couch, stares into the camera, and smokes a cigar. According to Geldzahler, Warhol was absent during most of the filming. Alone in the room and faced with the scrutiny of the running camera, at first Geldzahler challenges the unrelentless stare of the apparatus. But his initial triumphal pose soon changes to expressions of boredom and discomfort. Finally, he curls up into an almost fetal position, waiting for the camera to run out of film.

Soap Opera

1964, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 47 mins

Gregory Battcock, Rufus Collins, Jane Holzer, Gerard Malanga, Ivy Nicholson, John Palmer, Henry Romney

To have Jane Holzer star in Soap Opera was certainly a useful asset, considering her glamorous aura as a successful model, trendsetter and New York social celebrity. In 1964 Tom Wolfe even dedicated an ironic essay to the woman and her status, calling it ‘The Girl of the Year.’ In her first role in a Warhol movie, she stars in a series of small, silent, plot-free domestic situations, which are intercut with sound footage from television commercials for broilers, dishware, ovens, and shampoo. These commercials also gave Soap Opera, which was never completed, its subtitle: The Lester Persky Story. Lester Persky, a friend of Warhol’s, was the producer of these commercials in the 1950s. The film was not only an experiment with Pop imagery but also a tribute to him.

Couch

1964, b&w, silent, 16 fps, 59 min

Binghamton Birdie, Rufus Collins, Gregory Corso, Allen Ginsberg, Kate and Piero Heliczer, Jane Holzer, Jack Kerouac, Mark Lancaster, Joe LeSueur, Naomi Levine, Gerard Malanga, Taylor Mead, Billy Name (Linich), Ivy Nicholson, Ondine, Peter Orlovski, John Palmer, Amy Taubin, Gloria Wood

The title refers to an old maroon couch, a protagonist in its own right and a central meeting point at the first Factory on 47th Street. The actors in Couch pursue a variety of activities around and on the prominent piece of furniture. Factory members and other personalities are recorded taking naps, engaging in sexual acts – even repairing a motorcycle. The sexual explicitness, especially in terms of homosexuality, represented a major break with conventions at the time. The same applies to the use of camera. It never moves but just records everything that appears before its lens, including people blocking the view or passing through the picture. The whole idea was to embrace and incorporate arbitrary situations and coincidences into the film.

Mario Banana (No. 1) and Mario Banana (No. 2)

(No. 1) 1964, color, silent, 16 fps, 4 mins; (No. 2) b&w, silent, 16 fps, 4 mins

Mario Montez

Mario Montez, the attraction in Harlot, stars in Mario Banana. He is filmed eating a banana, hinting bluntly at the metaphoric possibilities. Whereas the first of these two screen tests is filmed in color, the second is in black and white. Montez made his first screen appearance in Jack Smith‘s underground classic Flaming Creatures. He took his screen name from Maria Montez, his favorite B-movie actress. His role in Mario Banana made him Warhol‘s first major superstar in drag. Moreover, he became one of the first transvestite actors recognized by the mainstream media. Curiously, Montez never felt comfortable wearing drag in public, always calling women’s apparel his ‘costumes.’ After years as a successful actor in many underground movies, Montez abandoned his stage moniker in favor of his real name, René Rivera.

Harlot

1964, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 67 mins

Philip Fagan, Harry Fainlight, Carol Koshinskie, Gerard Malanga, Mario Montez, Billy Name (Linich), Ronald Tavel

Framed as a family picture, the center of attention in Harlot is transvestite Mario Montez, dressed in drag and wearing a platinum-blonde wig, who plays the actress Jean Harlow. Seated next to him on the Factory couch is the voluptuous Carol Koshinskie, as Harlow’s lesbian lover. Holding a fluffy Angora cat, she stares vacuously at the camera. Behind the couch are two mute honor guards: Gerard Malanga, in a suit, and poet Philip Fagan. Most of the plot revolves around Montez eating bananas in increasingly explicit ways. Halfway through the film, Montez starts flirting with Malanga, gets up stolidly and kisses him before returning to the pleasures of tropical fruit. Although it was Warhol‘s first sync-sound film, nobody speaks on shot. Instead, the soundtrack is improvised off screen by the trio Ronald Tavel, Harry Fainlight and Billy Name.

John and Ivy

1964, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 33 mins

Sean Bolger, Ivy Nicholson, John Palmer, Darius de Poleon

Essentially a domestic-realism documentary, the film portrays John Palmer and Ivy Nicholson in their East Village apartment on a cold January day in 1965. Palmer, a filmmaker, was involved most notably in the production of Empire and also worked on several other Warhol movies. Ivy Nicholson was a highly successful fashion model and appeared in a couple of Warhol features. John and Ivy depicts the family at home with the use of a stationary camera pointing through a doorway into their tiny, cramped kitchen. A beam on the left side of the frame structures the image into a one third/two thirds composition and further stresses the constriction of the space. Inside the kitchen, the couple is shown drinking and dancing. Even the two children get a short cameo, while a live radio blares in the background.

Screen Test No. 2

1965, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 67 mins

Mario Montez, Ronald Tavel (heard off screen)

A departure from the usual screen tests that Warhol made at the Factory, Screen Test No. 2 is a merciless inquisition of drag superstar Mario Montez. Off screen, Ronald Tavel, who is also responsible for the script, explains to Montez that he is auditioning for the role of Esmeralda in a movie version of Hugo’s Notre Dame de Paris. What starts out as a regular test soon turns into a tour de force for Montez, as Tavel relentlessly demands that he do fatuous and humiliating tasks. All the while the viewer waits for Montez to break into an on-screen outrage. But Montez, nervously brushing his wig, responds to all questions and requests with bravura, fully believing in his created persona. The depiction of this interplay – the reaction on screen to what is happening off screen – is a common theme in Warhol’s oeuvre.

Poor Little Rich Girl

1965, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 66 mins

Edie Sedgwick, Chuck Wein (heard off screen)

Poor Little Rich Girl not only pays tribute to a 1936 movie of the same name starring Warhol’s childhood idol, Shirley Temple, but also delivers an adequate description of its protagonist, Edie Sedgwick. The beautiful, vivacious descendant of a prominent New England family, Sedgwick possessed the radiant screen presence Warhol looked for in his Factory superstars. He originally planned to capture 24 hours of Sedgwick’s life on camera but never fully realized his goal. Two reels of the film document Sedgwick waking up in her apartment, engaging in her morning toilette, and talking to an off-screen Chuck Wein. A problem with the camera lens resulted in the first reel being filmed totally out of focus and turning Sedgwick into an aloof presence. Warhol shot the second half in focus and added it to the blurred portion, giving the images an immediacy that emphasizes the contrast.

The Life of Juanita Castro

1965, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 66 mins

Waldo Diaz Balart, Electrah, Marie Menken, Mercedes and Marina Ospina, Amanda Sherill, Elisabeth Staal, Harvey and Ronald Tavel, Ultra Violet

Based partly on an article from Life magazine in which Fidel Castro’s sister Juanita called him a tyrant, The Life of Juanita Castro is an absurdist satire. Juanita, played by Marie Menken, takes center stage. The men at her side – Fidel and Raoul Castro and Che Guevara – are played by an all-female cast. They address a camera they believe is filming them, whereas the actual recording is being done from a skewed angle to the right. Consequently, whenever an actress starts a passionate speech and approaches the camera for a close-up, she disappears from the frame. To take the absurd situation a step further, screenwriter Tavel also appears on stage, reading the script aloud and feeding the players their lines.

Horse

1965, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 100 mins

Gregory Battcock, Tosh Carillo, Dan Cassidy, Norman Robert Glick, Larry Latreille, Edie Sedgwick, Ronald Tavel, Harvey Tavel, Andy Warhol

Horse, staged at the Factory, is a parody of the Hollywood Western genre and its inherently homosexual subtexts. The scenario, written by Ronald Tavel, involves a rented stallion and four young men dressed in vaguely Western clothes. Incorporated into the frame is the film production itself, with various onlookers and technicians appearing in the frame but outside the staged narrative, which relies on cue cards off screen, from which the actors get their instructions and dialogue. Reel one features the cowboys sitting in front of the horse, suggestively petting and performing tricks on it. The second reel takes leave of the plot, showing just a full-frontal shot of the horse being fed by its trainer. Reel three returns to the narrative to show the cast playing strip poker before getting into a mix of sadomasochistic games and an absurd playback opera performance of Gounod’s Faust.

Outer and Inner Space

1965, double screen, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 33 mins

Edie Sedgwick

Warhol was one of the first artists to work with video. In Outer and Inner Space, with its quadruple portraits of Edie Sedgwick, he used video to establish a strong formal and aesthetic relation to the serial paintings of movie stars he did in the early sixties. Two 33-minute reels projected simultaneously show Edie Sedgwick positioned in front of a TV set on which a prerecorded videotape of herself is running. The image on the TV displays a close-up of her head facing right. Reacting to this image and having a conversation with someone off screen is the ‘live’ Sedgwick, who sits to the right of the TV, facing left. Her position occasionally creates the illusion that she’s talking to her own image. Confronted with the video portrait, Sedgwick clearly is discomfited by the impassive image on the screen. Warhol tantalizingly captures this palpable tension between the ‘real’ person and the reductionist image.

My Hustler

1965, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 67 mins

Paul America (Johnson), Joseph Campbell, Genevieve Charbon, Dorothy Dean, Ed Hood, John McDermott, Paul Morrisey

My Hustler shows signs of a shift toward a more familiar cinematic look, complete with edited cuts, a panning camera and a consecutively played out plot. A beach house on Fire Island is the home of Ed Hood, a middle-aged literary scholar, who rents Paul America from Dial-a-Hustler only to find himself in competition with his neighbors, Joe Campbell and Genevieve Charbon, who likewise long for this young all-American stud. First Genevieve makes a move, flirting with Paul on the beach. After a dramatic change from the open space of the beach to an enclosed bathroom, it is Campbell’s turn to seduce America. As an old-time hustler himself, he lectures Paul on how to succeed in the business. The film captures the exploitation of human relationships in a class society in which love is a mere commodity.

Camp

1965, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 67 mins

Jody Babs, Tally Brown, Tosh Carillo, Jane Holzer, Donyale Luna, Gerard Malanga, Mar-Mar, Mario Montez, Fu-Fu Smith, Jack Smith, Paul Swan

Staged in the style of vaudeville theater, with Gerard Malanga as the host, Camp shows a cast of Factory regulars performing various acts. Paul Swan begins by dancing to the music of Wagner and is joined by Jane Holzer. Mario Montez performs ‘If I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate,’ while the camera frantically zooms in and out. Mar-Mar is dressed as a clown and behaves accordingly. Jody Babs reenacts ‘Let Me Entertain You.’ Gerard Malanga recites a poem after which singer Tally Brown introduces Jack Smith, who declines to perform. Fu-Fu Smith creates an oval out of miniature train tracks. Luna, the final act, uses the stage as a virtual catwalk. Her performance slowly evolves into a sensual dance which stops abruptly at the end of the reel.

Paul Swan

1965, color, sound, 24 fps, 66 mins

Paul Swan

Warhol’s fascination with dancing – apparent even in photos from his time at college, in which he can be seen posing as a dancer – reaches a climax in Paul Swan, a study of the American dancer, poet, painter, and actor in both theatrical productions and silent movies. Paul Spencer Swan, an early pioneer of aesthetic modern dance in the 1920s, held weekly evening recitals in his studio for over 50 years without changing the mode of presentation, the dances or the costumes. In Paul Swan, he restages his older performances, which seem awkward at first glance but soon emerge as serious small acts, diligently staged and featuring a variety of outfits. The total lack of artifice that characterizes these costume changes, which are captured by Warhol’s camera, provides an interesting contrast to the exaggerated theatrical contrivance that marks Swan’s performances.

Mrs. Warhol

1966, color, sound, 24 fps, 67 mins

Richard Rheem, Julia Warhola

An intimate portrait of Julia Warhola, Mrs. Warhol provides a glimpse into the world of the tiny old lady in her small basement apartment on 1342 Lexington Avenue in New York, where she and her son lived for almost 20 years. Although Julia Warhola kept to the housekeeping, she had an artistic sensibility that left its mark on Warhol. In Mrs. Warhol she is filmed going about her domestic routines, while constantly talking in an unintelligible, heavy Czech accent. The sketchy plot has her playing an aging star with many former husbands. Richard Rheem, an intimate friend of Warhol’s who stayed in his town house for almost two months, plays the part of her current spouse. Rheem‘s friendship with Julia is apparent in the way he badgers her affectionately. She in turn makes him scrambled eggs and teaches him how to iron a shirt.

The Velvet Underground and Nico

1966, b&w, sound, 24fps, 66 mins

Ari Boulogne, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, Gerard Malanga, Billy Name (Linich), Nico, New York City Police, Lou Reed, Stephen Shore, Maureen Tucker, Andy Warhol, Mary Woronov

The first reel of The Velvet Underground and Nico shows the band in a hypnotic jam session at the Factory. Nico, German model and singer, strikes a tambourine while her son Ari plays on the floor. Unlike the camera work in other Warhol films, here the camera actively underlines the rehearsal with wild pans, restless psychedelic zooms, and images in and out of focus. The jam session ends abruptly in the second reel when members of the New York City Police Department burst in to pursue a complaint about the noise. At the same time the camera pulls back, providing a rare wide-angle shot of the deep space of the Factory and a view of Warhol talking to the police, while the rest of his superstars mill around.

Hedy

1966, b&w, sound, 24 fps, 67 mins

Randy Borscheidt, James Claire, John George, Rick Lockwood, Gerard Malanga, David Meyers, Mario Montez, Arnold Rockwood, Jack Smith, Ingrid Superstar, Harvey Tavel, Ronald Tavel, Mary Woronov

Hollywood starlet Hedy Lamarr made headlines in January 1966 when she was arrested for shoplifting. In Hedy, written by Ronald Tavel, Mario Montez traces Lamarr’s travails in the style of absurd theater. All action takes place on one set. Warhol uses a few props to represent different locations. After an opening close-up of Hedy getting a face-lift, she succumbs to kleptomania, gets caught, and is interrogated by Mary Woronov, who plays a detective. A short excursion to Hedy’s apartment, filled with stolen goods, is followed by a court scene. Five of her ex-husbands testify at the trial. Warhol’s diversion of the focus away from the action to capture background trivia is reflected in Montez’s performance as a narcissist dame detached from the melodrama in which she’s embroiled.

Bike Boy

1967-1968, color, sound, 24 fps, 109 mins

Bruce Ann, George Ann, Brigid Polk (Berlin), Bettina Coffin, Vera Cruz, Joe Spencer, Ingrid Superstar, Viva, Ann Wehrer, Ed Weiner

In a series of episodes, Bike Boy indulges in confronting a naive blue-collar biker with the superstar entourage of the Factory. The film opens with the camera lingering on the immaculate nude body of the showering protagonist, Joe Spencer. It cuts to a boutique where two extravagant homosexuals, who also provide the chatter on the audio track, outfit Spencer for the New York scene. After a short intermezzo in a flower shop, Spencer is shown conversing with or being lectured by Factory regulars. The final scene leaves him in the arms of Viva who, with her mixture of naivety and deadpan remarks, not only renders their lovemaking hilariously absurd but also underlines the stark contrast between social reality, represented by Spencer, and the hip magnetism of Warhol’s entourage.

The Nude Restaurant

1967, color, sound, 24 fps, 100 mins

Julian Burroughs, Joe Campbell, Electrah, Taylor Mead, Allen Midgette, Billy Name (Linich), Rod La Rod, Ingrid Superstar, Louis Waldon, Viva

Members of an all-nude cast enjoy themselves in The Nude Restaurant. Viva, making her film debut for Warhol, plays a waitress constantly hit on by male customers. It is Viva’s incessant talking, her free-associating, and her forceful personality that propel the film. The only player possibly on a par with her is Taylor Mead, with his impish looks and spontaneous shenanigans. Eavesdropping on conversations, the camera records discussions ranging from Catholic priesthood to the Vietnam War, obviously a political issue even among the Factory’s superstars. Aesthetically interesting is the excessive use of the ‘strobe cut,’ a cinematic technique that entails turning the camera on and off, thus interrupting the flow and rhythm of the film.

Lonesome Cowboys

1967-1968, color, sound, 24 fps, 109 mins

Julian Burroughs, Joe Dallesandro, Eric Emerson, Francis Francine, Tom Hompertz, Taylor Mead, Alan Midgette, Viva, Louis Waldon

The last film wholly attributable to Warhol, Lonesome Cowboys tries to fathom the homoerotic impetus of the Western genre. Shot on location in Tucson, Arizona, the film features handsome drifter Julian, the driving force of the narrative. Played by Tom Hompertz, Julian joins a close-knit gang of homosexual cowboys. His arrival fuels the desire of the gang members and threatens to disrupt the group’s solidarity. An even greater menace to their unity is townswoman Ramona, played by a hyperactive Viva, who is sexually involved with Julian. The cowboys’ repressed sexual tensions culminate in a pseudo rape scene in which the fully clothed men violate Ramona. Neither her hilarious sidekick, ‘Nurse’ Taylor Mead, nor the cross-dressing sheriff comes to her rescue. Finally Julian, restless and unpersuadable, takes off for California with gang member Eric Emerson.