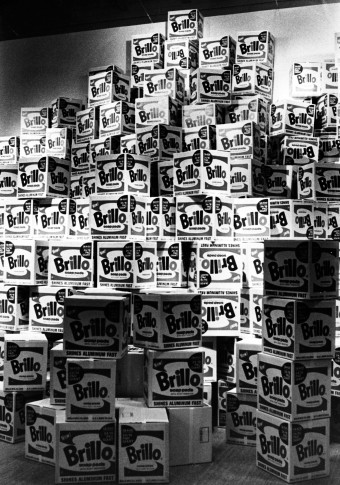

Brillo Soap Pads Boxes at Warhol´s retrospective at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 1968. Photo: Nils-Göran Hökby

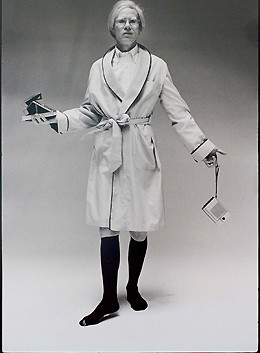

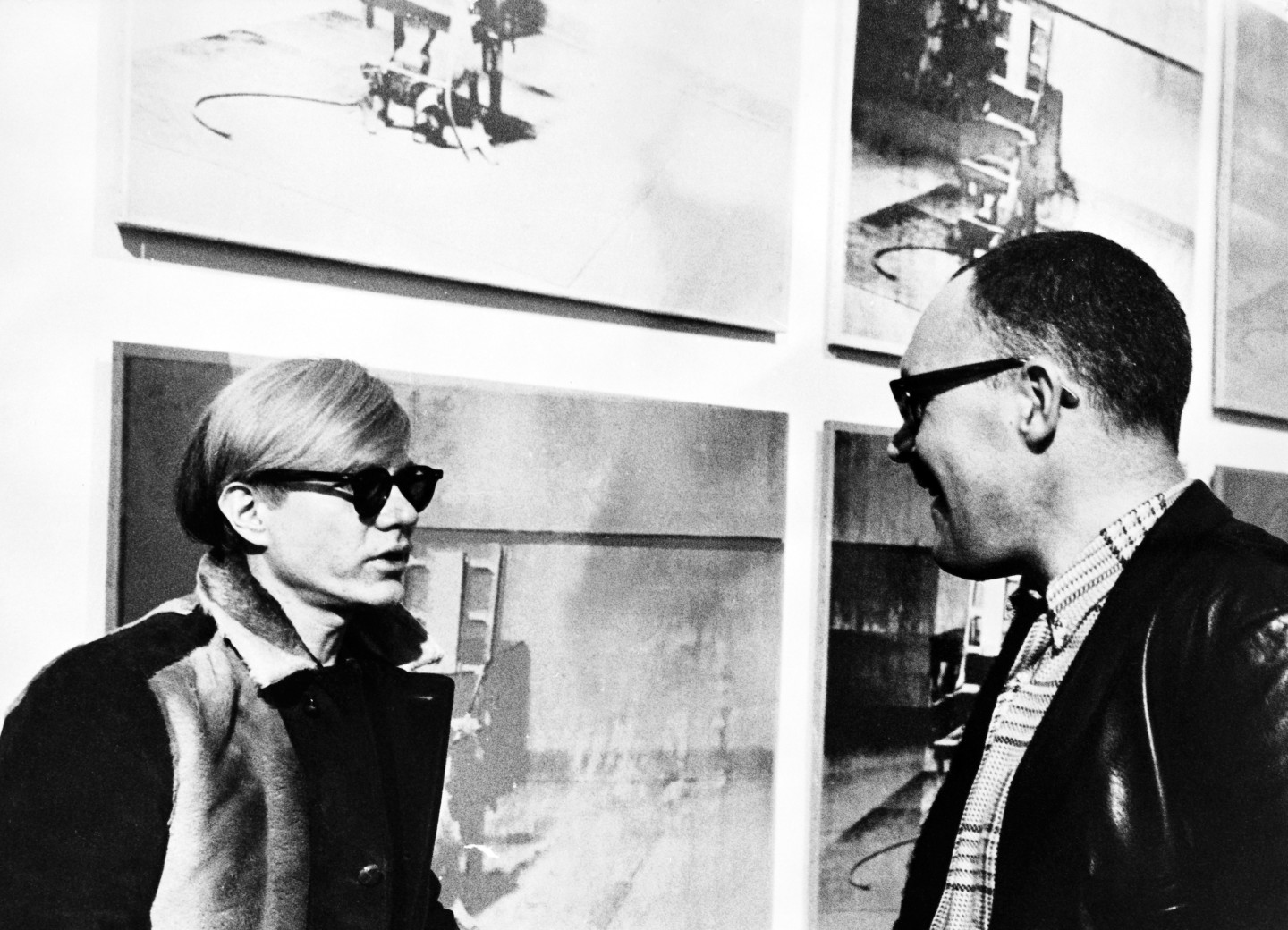

With Andy Warhol 1968

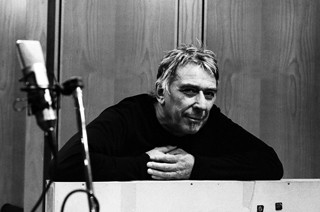

Text: Olle Granath

The exhibition had been designed by a team, which, in addition to Warhol himself, consisted of Pontus, Billy Klüver, and Kasper König. One of the basic themes was repetition; there were to be many works and few motifs: Marilyn Monroe, flowers, the electric chair, Brillo boxes, wallpapers with red cows on a yellow background, the helium-filled balloons of metallic plastic film called Clouds, and short loops of some of his most famous films, such as Sleep, Eat, and Empire State. The film loops were to be shown on daylight screens alongside the paintings as if they were moving paintings. An important part of the exhibition was the production of a book. It was not supposed to be an analytical catalog of Warhol’s work, but a book that conveyed his aesthetics without heavy texts.

There were numerous practical problems. The cow wallpaper was to cover the main west-facing façade of the museum building. How to put it up? After several experiments with various materials and many consultations, we reached the decision that the best way was to erect some ordinary scaffolding in front of the façade, on which standard- sized Masonite boards were attached. The ‘wallpapering’ was done by the painters regularly employed by the museum. When the wallpapering was finished, two and a half cows remained.

The yardstick had obviously worked. The wallpaper on the façade glowed. In the defoliated early spring, the cows could be seen from as far away as Slussen.

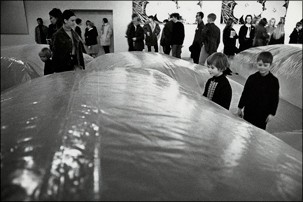

Infatable plastic clouds at the grand opening of Warhol’s retrospective at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm 1968.

Photo: Bror H. Gustavsson

How to make the film loops visible in the harshly lit museum gallery? The large paintings of flowers and electric chairs devoured light. We were offered an entire battery of discarded floodlights from Swedish Television for a reasonable price. In those days, daylight projection was not particularly advanced, but the main camera shop in town had a new type of silver screen that produced a pretty good rendering in well-lit rooms. The screens were mounted on stretchers the same size as some of the paintings, and we acquired a number of 16 mm projectors. We were a long way from the flat screens of today. The film loops turned out to be another problem. Despite intensive correspondence, first by letter, then by telegram and finally by phone, no films arrived. The Factory blamed the lab which hadn’t delivered the material. We eventually realized that there were copyright problems, which were more complicated for the films than for the paintings. We never received any films.

We sent an SOS to our friends Anna-Lena Wibom and Nils-Hugo Geber at the Swedish Film Institute. They also had copyright problems, but they found an old circus film which wasn’t copyrighted and which we edited. The loops were short and I especially remember an elephant in a hippodrome who just stepped up on a drum; it never stepped down. By now, it ought to have reached the moon! Both Pontus and I were rather nervous about what Warhol, and especially his director Paul Morrissey, would think about this substitution. Warhol was fascinated. For a long time, he watched the elephant that just stepped up and stepped up and stepped up.

However, our problems weren’t over. We began to receive discouraging messages from Billy saying that he couldn’t get hold of any Clouds. You have to remember that exhibitions like these had an unbelievably low budget and it was expensive to weld together the metallic plastic film of the balloons. Moreover, on arriving in Stockholm they were to be filled with helium gas, which was very expensive. I suspect it would have gone far beyond the budget. Instead, we got hold of large transparent plastic bags which we filled with air and placed on the floor. Their static electricity attracted all the dust on Skeppsholmen. The visitors had to wade through these sacks to reach the paintings. I wonder if such ‘clouds’ have ever been seen in a Warhol exhibition, before or after.Displaying the number of Brillo boxes required by the theme of repetition involved an expensive production as well as an enormous shipping volume. Warhol suggested that the boxes should be made in Sweden, but that wasn’t cheap either and we were running out of time. At this point someone came up with the brilliant idea of buying five hundred cardboard boxes from Brillo. They were shipped in flat packs across the Atlantic and folded at the museum. The museum attendant and I became real wizards at folding boxes. The result was a magnificent mountain of boxes which accentuated the repetition theme of the exhibition.After these non-deliveries and the resulting improvisations one would imagine that the exhibition was going to be a flop. This was not the case. It was a hit. Andy Warhol and his friends Viva and Paul Morrissey were very pleased and spent some intensive days in Stockholm, which, among other things, included a screening of the Vilgot Sjöman movie I Am Curious (Yellow), which Warhol watched with admirable concentration while Paul Morrissey succumbed to jetlag and slept heavily. To entertain the gang, which preferred night to day, I had engaged the musician Bill Öhrström, with the help of whom I got to experience a night-time Stockholm that, apart from the jazz club Gyllene Cirkeln, I hardly knew existed.

Needless to say, the large, screen-printed paintings were the visual centerpiece of the exhibition. In the south section of the first gallery, we hung ten flower paintings in dazzling colors. Up to that point, they were the largest ever produced. In the north section, there were the electric chairs, one chair in each painting, in colors that produced a striking contrast to the grim subject, and on the divider wall at the staircase leading to the small cinema, one could find a number of Marilyn portraits which continued the wallpaper theme of the exterior.

Pontus Hultén had an agreement with Andy Warhol: the Moderna Museet paid for the production of the paintings in exchange for a flower painting and an electric chair painting. In retrospect, it is easy to see that this was one of the many brilliant deals that Pontus Hultén struck on behalf of the Moderna Museet. There were some indications that Warhol’s American gallerists weren’t as pleased with the deal which had been made above their heads.

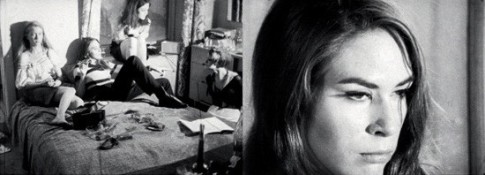

In the small cinema we rigged up double projectors and double screens and showed the film Chelsea Girls several times a week. The film is a kind of purgatorial voyage through the lives of the New York bohemians who stayed at the Chelsea Hotel and in Warhol’s studio the Factory.

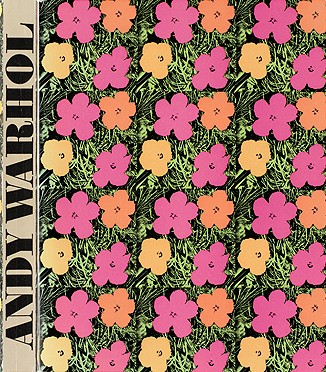

The book was an important part of the exhibition. I was aided by the brilliant team of John Melin and Gösta Svensson who quickly realized that it was a project for a newspaper printer and booked the printer of the daily Värnamo Nyheter. The photographers Billy Name and Stephen Eric Shore had edited their series of images of life with and around Warhol, so we just used their material as it was. The images of Warhol’s works were to comprise the theme of repetition as well as the retrospective element that was not present in the exhibition. The image material was abundant, so it was an easy task.

There was also to be a section of texts. One day, Pontus brought me a box, almost the size of a Brillo box, and told me that it contained everything written by and about Andy Warhol (today the equivalent would probably be two truck loads). My job was to read it all and present a proposal for a manuscript with Swedish translations. After a couple of nights of reading and taking notes I delivered a script to Pontus and awaited his reaction with great anticipation. ‘Excellent,’ Pontus said when he called me, ‘but there is a quotation missing.’ ‘Which one?’ I said. ‘In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes,’ Pontus replied. ‘If it is in the material I would have spotted it,’ I told him. The line went quiet for a moment, and then I heard Pontus say, ‘If he didn’t say it, he could very well have said it. Let’s put it in.’ So we did, and thus Warhol’s perhaps most famous quotation became a fact.

When it was time to make the exhibition posters we decided to use the quotations instead of the customary reproduction of a painting. We produced a series of some ten posters with different quotations in the hard-hitting and legible typography characteristic of John Melin. The book was inexpensively produced and we had seriously underestimated the demand. It was reprinted several times, which, considering the uncomplicated printing method, allowed us to add images from the opening and the installation. On a bleak winter day with the sky full of wet snow, Gösta Wibom, Pontus’ brother-in-law, came to Skeppsholmen leading some cows by a rope. Some years earlier, Gösta had provided Robert Rauschenberg with a cow for his happening for the event 5 New York Evenings at the Moderna Museet. The cows just stood there in the sleet and gazed absent-mindedly at their Pop-version friends while the master photographer Lennart Nilsson and the museum’s curator Nils-Göran Hökby kept snapping away. An image by the latter was printed in the final edition of the book.

Pontus had agreed with Warhol to produce a deluxe edition of the book, seeing its great desirability. One hundred gilt-edged copies were printed and placed in a Plexiglass box with black sides. They were to be signed by Warhol, but that never happened. A few months after the exhibition in Stockholm, Warhol was shot by Valerie Solanas and the lines of communication were broken for some time. When Pontus left the Moderna Museet for Centre Pompidou the books remained in a box and were forgotten. In the spring of 1976 Warhol visited Stockholm for an exhibition of ‘dogs and cats’ at a gallery on Strandvägen. During the dinner on the opening night I asked him if he remembered the book and if he wanted to sign them, provided that I could find them. Sure, no problem. The museum director Karin Lindegren gave me permission to visit the museum’s central storage, which was located below the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design on Valhallavägen, in order to look for the books, which I found. Warhol was collected at his hotel and together we sat in the museum’s office where he signed them. The books were sold and, as expected, became a collector’s item. However, deluxe edition or not, the book primarily reminds me of one of the perhaps strangest exhibition productions I have ever been part of. After Stockholm, the exhibition traveled to, among other places, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the Kunstnerernes Hus in Oslo. It turned out to be a landmark in Warhol’s career and a roundup of what had passed. After the shooting in Union Square he was to take a somewhat different path.

Olle Granath is a former director of the Moderna Museet and now the permanent secretary of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, both in Stockholm, Sweden.