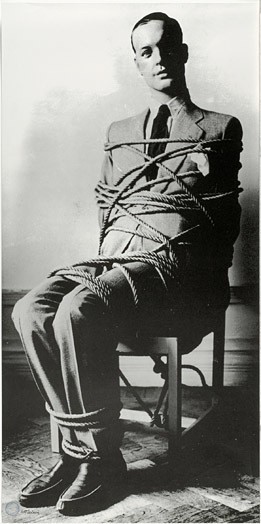

Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd

Mascot för Rörelse i konsten 1961, 1961

© Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd/BUS 2011

14.6 2011

50 years since Rörelse i konsten (Movement in art)

Performances and happenings were a central part of Rörelse i konsten and, on June 18, Otto Piene will also be reconstructing the performance work Proliferation of the Sun during the conference An experimental conference on art and science to challenge the mid-summer sun.

Behind the exhibition in 1961 lay Moderna Museet’s Director Pontus Hultén, who worked closely with Daniel Spoerri and Carlo Derkert. The core of their project was showing movement as a revolutionary force in 20th-century art, and sketching out its history, from futurism right up to contemporary artists showing totally new works. Hultén’s view was that the temporal dimension in kinetic works involved a total renunciation of the sacred values of older art, which he summed up as “definitive beauty and eternal order”. Motion thus also became the perfect metaphor for total freedom and anarchy.

The debate in the Swedish artworld and media was long overdue. Enthusiastic tributes were interspersed with critical voices that were not slow to make sarcastic pronouncements, such as that the Gröna Lund amusement park had now opened a branch at the museum. Some artists even took up the cudgel. The young Öyvind Fahlström wrote enthusiastically. In contrast, Sven Erixson was furious, and ended up quarrelling with his erstwhile friend Bror Hjorth, who went to the exhibition’s defence. But one thing is clear, Rörelse i konsten made a major impression and was like nothing else.

More depressing is the fact that it was a very male affair. Of the exhibition’s 233 works by 83 artists, only eight were made by women. Cecilia Widenheim writes about this in “Framtiden som vi minns den” (The future as we remember it), published in the catalogue Jean Tinguely, The Future As We Remember It (Henie Onstad Art Centre 2009) and asks rhetorically “Is it the case that only male artists, with the exception of Niki de Saint Phalle, are attracted by the theme of motion? Or was the field quite simply so dominated by male theorists, technicians, critics and artists that women artists were not allowed in?”

At any rate, the idea of movement came to be central to the Pontus Hultén’s entire working life. Already before Rörelse i konsten, he was involved in the Le Mouvement exhibition at Gallerie Denise René in Paris, and, for instance, published texts about Jean Tinguely, who he also staged an exhibition with at Galerie Samlaren in Stockholm in 1955. His subsequent history is full of related projects and, in 1968, he mounted the historically encyclopaedic exhibition The Machine. As seen at the end of the mechanical age at MoMA in New York. In it he went more deeply into humankind’s relationship with technology, emphasizing the artist’s role – in an age of mass production, consumption, and depletion of the world’s resources – in taking back the initiative from the machine. The mechanically mobile Study Gallery set up at Moderna Museet when Hultén donated his collection in 2005 can be seen as a logical endpoint to his work.

It is no exaggeration to say that Rörelse i konsten has been of crucial importance for both art history and Moderna Museet. It is not only the works displayed here that have ended up in our collection, several others have found their place in other contexts in the museum. Alexander Calder’s large outdoor work The Four Elements, for example, first came into existence for the exhibition, as did the museum’s famous copy of Marcel Duchamp’s large glass, which, together with Man Ray’s gallows mobile, can be seen in a surrealistic context a few halls away. But, beyond trophies that we can put on display, many of which unfortunately now have difficulty living up to the original idea of movement, the concepts and ideas behind the exhibition deserve to be viewed in the light of our own time. Rörelse i konsten inspires and encourages us to thoughts and ideas about what a museum can be, about art’s potential, the artist’s role and freedom, about critiques of consumption and civilization, cooperation and collective ways of working, and more. Recommended further reading includes the text by Cecilia Widenheim mentioned above, Hans Hayden’s and Marianne Hultman’s contributions to Moderna Museet’s The History Book, plus the book about E.A.T and Billy Klüver: Teknologi för livet. Om Experiments in Art and Technology.

The commemorative display will be on show in the collection until November, after which the spotlight will continue to be on the 50 year old Rörelse i konsten at The National Museum of Science and Technology, where the works will be contrasted with the work of another anniversarian: Christopher Polhem. In this encounter particular focus will be placed on the nature of humankind’s relationship with mechanics, ranging from complete devotion to the profoundest pessimism.

Published 14 June 2011 · Updated 4 March 2016