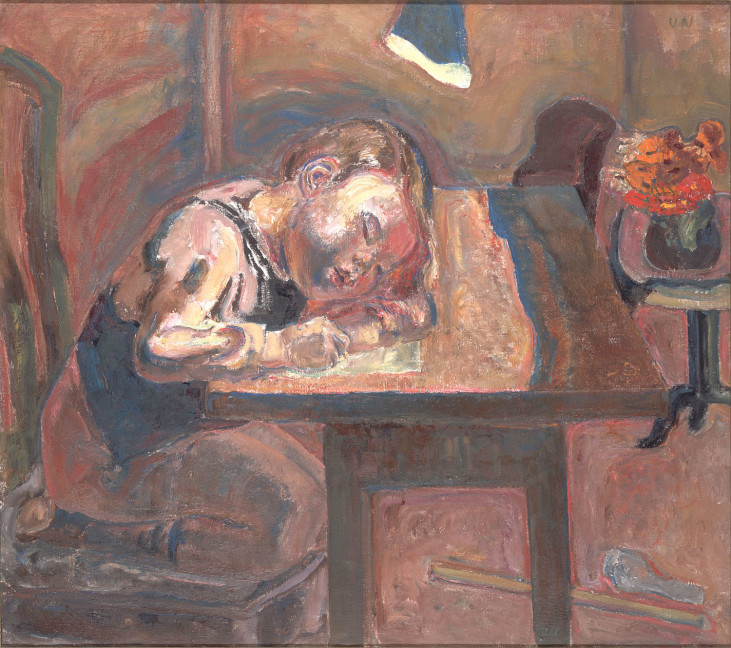

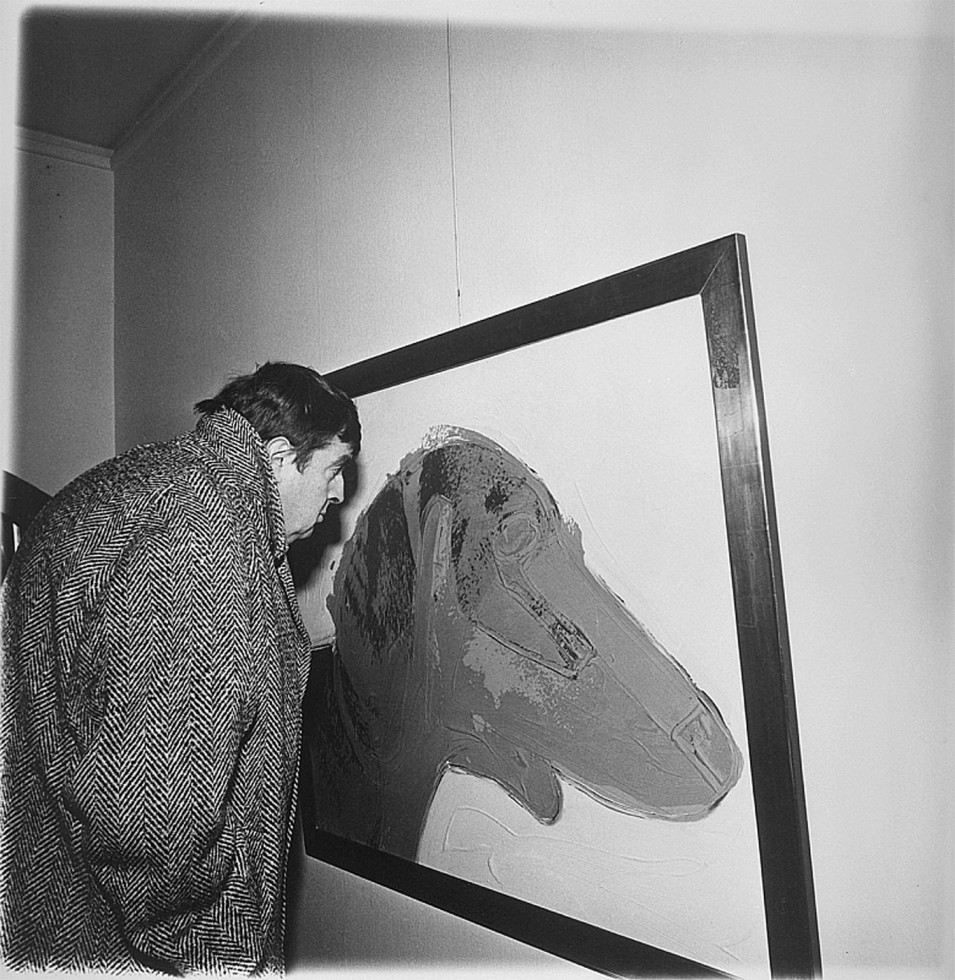

Hans Gedda, Professor Ulf Linde, 1978 © Hans Gedda

1.11 2013

With Ulf Linde an entire era comes to an end

With Ulf Linde an entire era comes to an end. Linde – the jazz musician, critic, professor, museum director, member of the Academy – was a guiding light on the art scene and his impact on post-war art can never be disregarded. Without him, the Swedish intellectual climate would have been different. Without him, discussions about what art is and should be would have taken a different course.

Again and again, Linde was at the centre of revolutionary debates on art. This was particularly the case in the early 1960s, when his book “Spejare” delivered an incendiary starting-point for an open concept of art based on the viewer’s active participation. And again, in the mid-1980s, when the discussion about the postmodern condition engaged with established notions of the creative self. In Sweden there was only one truly worthy target, who was always quick to respond. Only under such circumstances can an energetic debate arise. The slugger and elitist lived in the same body, and Linde summarised the philosophical challenge from an under-the-belt perspective that far from everyone found pleasing: “My arse is mine.”

Linde read Nietzsche and Wittgenstein enthusiastically, but he was never a systematic theoretician. His strength lay in his flashes of acute observation and his ability to capture the tone and specific atmosphere of works of art. He created condensed, sometimes veritably aphoristic texts and remained a musician in everything he did – whether he spoke, wrote or hung paintings in a gallery. For many years, his output as a writer was impossible to overview, dispersed in a plethora of minor publications and catalogues, but today a number of books are available with selected articles, an autobiography and a highly idiosyncratic collection of essays called Samelsurium. Linde wrote about Swedish poets and painters, which he also exhibited, most frequently at the Thielska galleriet (in itself a veritable Gesamtkunstwerk). He wrote about Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, about Siri Derkert and Wallace Stevens.

But above all, he wrote book after book about Marcel Duchamp. And in dialogue with the artist he recreated practically all his major works in perfect replicas that are now in the Moderna Museet collection. The impact of these replicas on Duchamp’s international reputation after the war can hardly be exaggerated. Ever since Duchamp’s first major retrospective in California in 1963, Linde’s replicas, signed by the artist, have been the centre of attraction. When Centre Pompidou opened in 1977, Linde and his kindred spirit Jean Clair (academy member and a furious critic of contemporary society) were responsible for the first extensive Duchamp retrospective in Europe, which consisted largely of the signed Stockholm replicas. Incidentally, Linde’s version of The Big Glass (with the remarkable title “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even”) is the most written-about, and beyond comparison the most financially valuable work, ever to have been created in Stockholm.

What is this painting about? A recurring idea is that the glass can be seen as the artist’s self-portrait. In an array of notes, called “The Green Box” (translated into Swedish by Linde) Duchamp calls the upper section “MAR” and the lower section “CEL”. Furthermore, his own name is inserted in the title of the work: MAR in “mariée” (Bride) and CEL in “célibataires” (Bachelors). If the glass is an image of his own self, it is indeed about a dismantled and conflict-filled subject. Early in his career, he created an androgynous alter ego with the enigmatic name Rrose Sélavy, with which he signed many of his works. No, Duchamp was never alone in his artistic practice. He had his friend Picabia. Then he had a number of remarkable collaborators in various parts of the world. The artist Richard Hamilton in London. The eccentric and esoteric art dealer Arturo Schwarz in Milan. And, most important of them all: Ulf Linde in Stockholm.

Linde devoted 60 years to trying to understand Duchamp’s oeuvre, whom he and many others considered to be the most innovative artist of the 20th century. I am grateful for the privilege of having been engaged in this quest in the most recent years. There is a mandatory journey that all young art historians and writers dream of. Everyone makes it: the Greyhound bus trip from New York to Philadelphia, where Duchamp’s broken original can be seen. Ulf Linde never made that journey. His fear of flying transformed his entire intellectual life into something so fantastic that it resembled a novel by Jorge Luis Borges. Instead, he created his own Duchamp works, perhaps even more perfect than the originals. Someone has compared this with the fact that Winckelmann never visited the Greece he dreamed of.

With all due respect for museum directors, without the right colleagues it can all be rather dull. In the 1960s, Moderna Museet was a small institution with a fairly diminutive audience, but with a strong intellectual charisma. And the credit for this was probably not just due to its daring director but at least as much to Ulf Linde. I’m sure he could be arrogant and intimidating at times, but he was also childishly curious about everything that caught his interest, anything that had the right tone and the right kind of intellectual playfulness. He was never uninterested or boring. An art historian with perfect pitch is a rare thing.

Daniel Birnbaum, director of Moderna Museet

This article was written by Daniel Birnbaum for Dagens Nyheter and was published on 14 October, 2013.

Published 1 November 2013 · Updated 18 February 2016