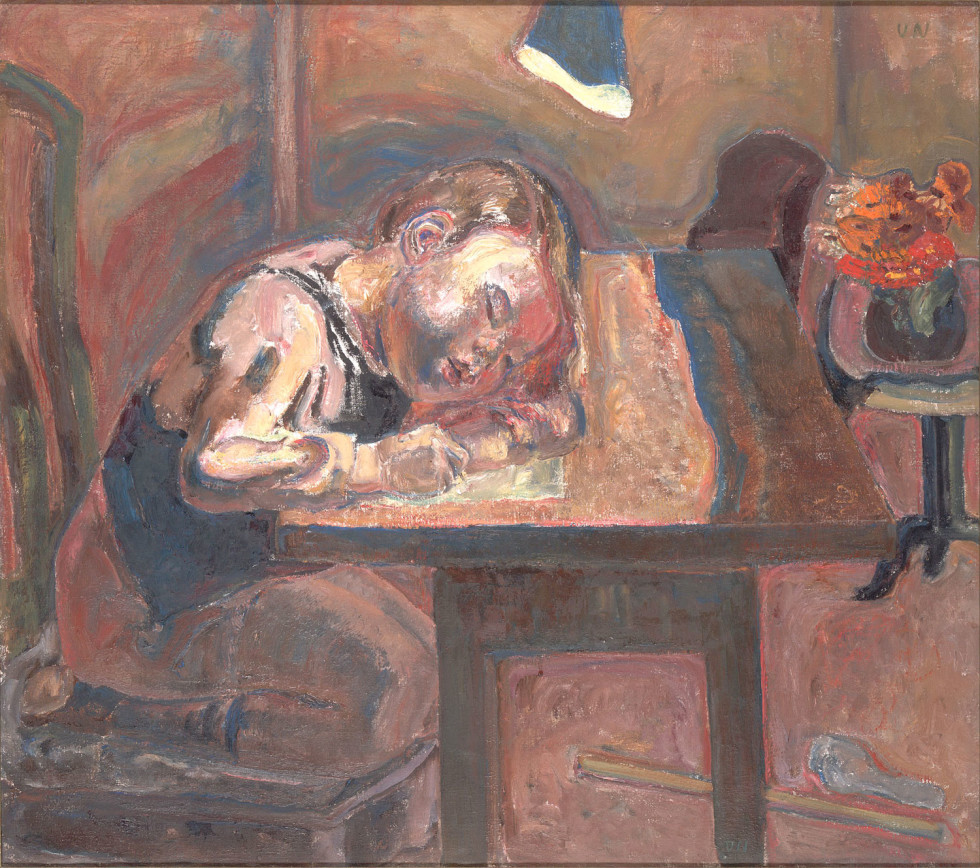

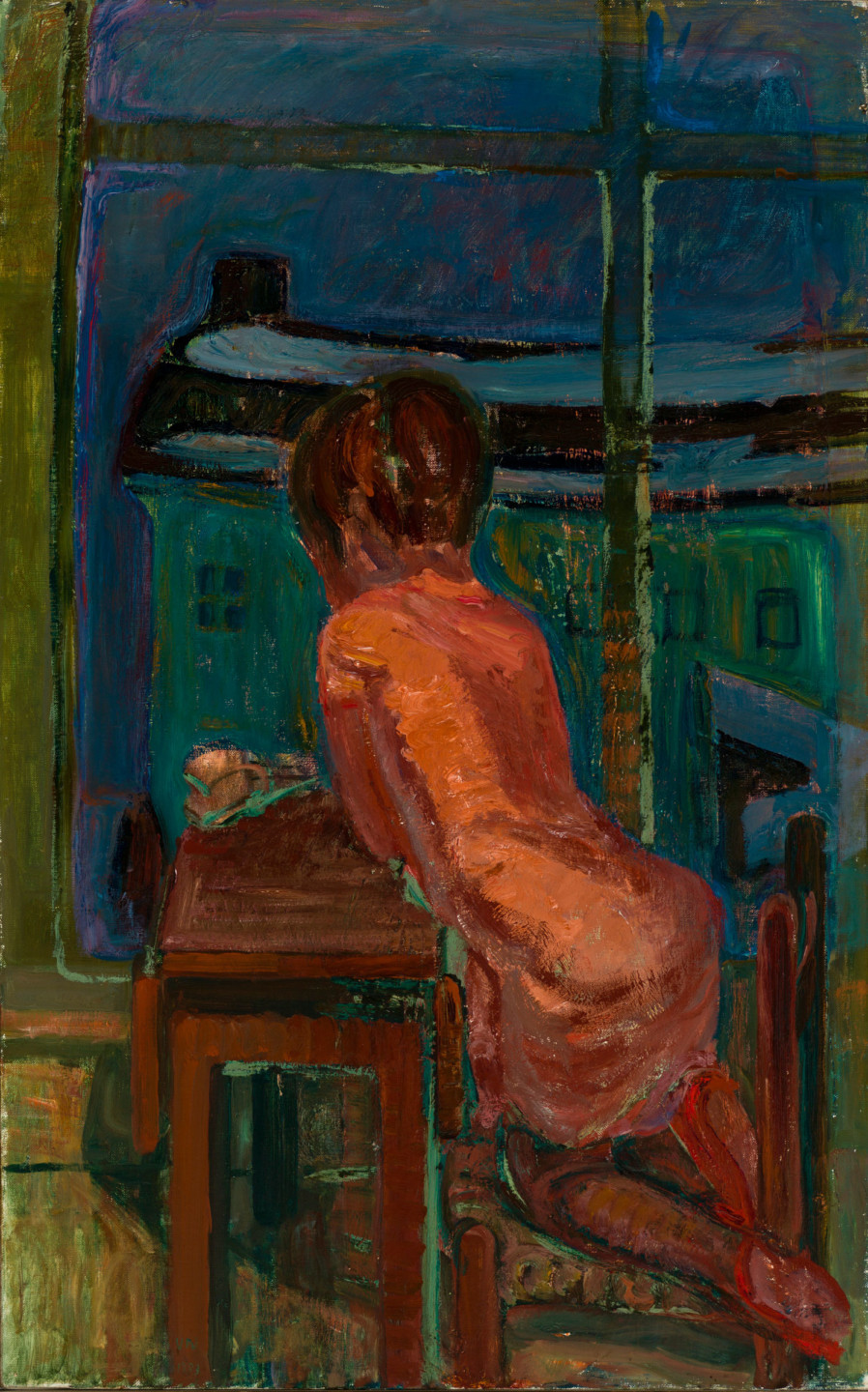

Vera Nilsson, Lampsken, ca 1930 © Vera Nilsson / Bildupphovsrätt 2016

18.1 2022

Read the short story “Stories, Lamplight”

Stories, Lamplight

by Karolina Ramqvist, 2021

The sky was an unusual color that evening. It was like a wet mix of the burnt yellows and pinks in my paint box, with a little gray out around the edges, as if a fire were burning behind the buildings and its smoke had settled in the distance.

I had taken a seat by the window so I could look out, as I would do, just for a short time to keep myself occupied, but ended up staying put because of the color.

It had a hold on me.

After a while, I started looking for her.

The street was bustling. Kids, bikes, dads and moms on their way home. But my mom wasn’t home yet.

She had picked me up as usual, but said she had to go back out. I couldn’t remember where.

It felt late.

I couldn’t help turning around to check that there was nothing in the hall, but then continued looking out the window.

It must have been rush hour. Down on the street, everyone was rushing this way and that. She would use those words sometimes when she picked me up. It’s rush hour, she’d say. It made her late.

I wanted her to hurry up so she could see the sky.

Buses rolled up to the stop and dropped people off and others were going in and out of the grocery store. I wondered what they were having for dinner and what I would be given.

She probably wasn’t at the grocery store, because if she’d gone there, then she’d be back by now. Neither had she gone to the laundry room, because she would have made me tag along, even though I didn’t want to; I hated it there. She’d give me the choice between going downstairs with her or waiting up in the apartment alone, and I’d always chose to go with her. She couldn’t be with any of the neighbors either, because we never visited the neighbors.

I hoisted myself up a bit to get one knee on the chair so I could lean even farther forward and get a better look.

I really wanted to catch sight of her down there.

Every time someone came walking down the sidewalk I had to be sure to look over really fast in order to see who it was, and if it wasn’t her, I’d quickly look in the other direction to see if she was coming from that way instead.

I looked here and there, everywhere, so much it almost hurt my eyes.

I wanted to discover her.

I wanted her to turn up out of the blue. It had happened before. She could suddenly appear, I knew she could, and I was after that feeling: the relief and joy of being together again, the surprise even though I shouldn’t have been surprised. I was waiting for her, after all.

Now waiting was all I was doing.

I wanted to see her from afar, as early as possible.

I leaned back a little and when I looked out, I lost my depth perception and all went flat, as if the view were painted on the windowpane or a drawing had been laid against the glass, and behind it was something else entirely.

An infinite space, perhaps.

I shook my head and blinked my eyes until the outside was back to normal.

Could she have come into the building while I was sitting here thinking? I thought I heard the elevator starting up, listened for the clack of her heels in the entrance hall, but there was nothing.

She might pop up somewhere outside, but I might also hear her, without forewarning. This I knew. And she might suddenly step into the apartment without me seeing or hearing anything. This had happened, too.

Did she say she had to go back to work?

I didn’t remember, but if she did, she’d be taking the bus. That’s where I should be looking. A drunk at the bus stop wobbled across the street, an old lady was dragging a trolley behind her, and I spotted one of the twins from the building next door.

But I didn’t see her.

The bus arrived and stopped and dropped people off and when it drove away again, there she was. My heart skipped a beat the second I laid eyes on her. Her red coat beamed through the atmosphere, a swift signal just for me, no one else had a coat like that. Though it was strange–hadn’t I just seen her coat in the hall?

I craned my neck and looked down the long hall and saw the coat over on the clothes hanger.

When I turned back around, I could tell it wasn’t her.

Even if she had owned two red coats, it couldn’t have been her–now I could see that she was walking a dog on a leash, and we didn’t have a dog. I really wanted one but we didn’t have one, so it couldn’t be her. Otherwise they were so alike. She was walking down the sidewalk with the dog, which looked small and shaggy, and I watched her until she was out of sight.

That’s when I noticed it was getting dark. It had turned blue out there. She’d call it “the blue hour.”

She should have been back by now.

Maybe she’d gone to that restaurant I was allowed to come along to sometimes, where they’d say that the blue hour was particularly lovely through the windows overlooking the park.

I closed my eyes and tried to picture her and call up an image of where she was. I shut them tight, but nothing happened.

I tried again and again.

When I looked up, the blue had deepened and settled over everything beyond the window. It was full twilight.

I felt stupid. I knew darkness could arrive in an instant, and yet I hadn’t been prepared.

Mom always said that, actually, everything was the same as it always was in the dark, it just looked different, but this wasn’t true.

If it looked different, then of course it wasn’t the same.

Nothing in our apartment was the same in the dark. I did not look over at the hall, but kept my eyes on the street, the people were dark spots below, like the woodlice in the courtyard, scurrying all around as soon as you turned over a rock.

I couldn’t make out faces anymore.

It was dark and she had yet to come home.

The blue hour wasn’t an hour at all. It went by much faster. And then where did the day go? Was night like a hood that got pulled over the day, or was night a dark vault that was always there, but only appeared once the day had gone?

I turned around and saw how different everything was. The corners had expanded and were reaching into the room, the furniture had become a blurred chain of islands, and at the far end, the hall opened up like a deep black hole.

I should have switched on the lamps while it was still light out, as I usually did when I’d be home alone after dark. But

I hadn’t thought I would be.

She hadn’t told me.

I needed to be thinking good thoughts.

The good thing about the night is that you didn’t notice how long it is. You go to bed and fall asleep and when you wake up in the morning, it’s as if it had gone by in a flash.

I wanted evening to feel like that, too, for it to go by as fast.

But even this scared me.

It was more than the light leaving. Something else would arrive. It felt like something would find its way into the apartment after dark.

I didn’t know what it was, but I used to feel it trying to get close to me or lying in wait in the hall. Sometimes it would lurk there in the daytime, too, and when the lights were on and when Mom was home.

I only ever ran through the hall.

And now I had to get up and walk over there and turn the light on, and go around turning on the lights in every room.

I counted to three.

I counted again and told myself that this had to be the last time.

Otherwise you’re nothing, I said. If you can’t even move, you’re nothing.

So on the count of four I tore myself from my seat and leapt from the window, ran past the islands and through the dusky room. When I reached the hall, I stuck my hand in, afraid that whatever was there would pull me in, then I stood on my tiptoes so I could reach the push-button for the light. I pressed it, but nothing happened.

I pressed it again, but it was still dark.

Then I forced myself into the darkness and pressed it one more time. I had never not seen the light turn on in the hall. Was this the doing of what was lurking there? Could it control every light in the apartment?

I was about to turn around and run back into the room, to the tall floor lamp in one of the corners which was easy to switch on, but instead I took the plunge and ran down the hall and into the kitchen toward the light switch by the kitchen door and flung myself at it. The fluorescent ceiling light flickered. It crackled from within, then brightened to a glow, slowly as if it were waking up after a long night’s sleep, and I climbed onto the stool by the sink and turned that light on, too.

When that was done, I turned on the ceiling lamp hanging over the table in the dining nook, exhaled, and sat down in its shine. Inside that beam of light was a protective space.

I sat there, breathed out, and listened to the buzzing fluorescent light.

Mom never turned the fluorescent light on, she hated its cold shine, its sound and flicker, but I needed all the light there was. I would make my way back through the dark hall and turn the light on in the other hallway and in the bathroom, too, so I could visit it later if need be.

But first I had to sit a little longer.

As long as I was in the lamp’s glow, it couldn’t reach me. Nothing bad could reach me here.

My papers and pencil lay on the table and the paint box on the sink, next to the water jar with the brushes.

I closed my eyes and said: Lights!

My voice sounded strange in the silence but I kept at it.

Turn on the lights! Dear God, make all the lights go on.

But when I opened my eyes, it was still dark in the hall and out in the other rooms.

Maybe she had gone back to work after all.

She loved her job. As long as you have a job you love, life will always be tolerable, she’d say.

Well, I had a job, too.

If I did some work myself, it would take my mind off the hall and what was waiting for me there.

The book was cut from two sheets of paper from the drawing pad and stapled in the middle, and when it was finished I would make another one, Mom said. On some of the pictures I had written the words by myself, but it was easier when she was there.

For me, letters were still a challenge.

I held the pencil and drew the first line of an N–for “nalle” or “teddy”–and it came out nice and straight, but when I added the slant it was harder to get it to meet the other line.

The book was about a teddy bear who woke up one day only to find he had come to life.

I wrote an A after the N, and L and E and that made me forget everything else. I drew the teddy bear and how surprised he looked when he realized that he was alive. Then I started a new drawing of him trying to talk to other stuffed animals.

All they could do was stare back at him.

He was the only one who had come to life.

What if my teddy bear had also come to life and was lying on the bed with the other stuffed animals, frightened by their silent faces and black eyes?

If I went out now and turned on the lights, I could go to my room and check. I’d just have to make it through the dark hallway, then it would be fine. I didn’t want to leave my spot at the table, but if I didn’t, I might be stuck here until she got home.

She might be gone a long time. It was a possibility.

What would I do if I needed the bathroom?

I could pee in the sink, but if it was dark in the hallway and the rest of the apartment, I might just stand there staring into the darkness, unable to jump up on the counter, I might freeze up and pee myself and still be wet when she got home.

I almost felt a little frozen already.

And what if the telephone rang? What if I had to run through the darkness to her bedroom to answer the phone?

What if she called to tell me where she was and I couldn’t pick up?

I had to go out and turn the lights on and fetch the teddy bear and blanket and bring them back in here.

As I was thinking that thought, the fluorescent bulb on the ceiling died and everything went quiet. I had prayed to God to turn the lights on for me, but instead he had made sure another light went out.

It was to show me that I had to do it myself, of course.

Some things are for you to handle.

Some things you must do on your own.

That’s just how it is.

I rested my head on the table, using my arms as a pillow, and thought about what it would be like to be holding the teddy bear here and now, a corner of blanket up to my nose, me taking in its smell.

With my pencil, I drew a line on the paper, the start of a new letter. I needed to think of something good to happen to the teddy, something that didn’t scare me, but this wasn’t easy.

Everything I came up with was horrible and everything I drew looked angry and mean, as if what was lurking in the hall were controlling my hand, too.

I let go of the pencil.

Forget about drawing the teddy, I’d draw a dog instead.

What if it had been her after all, and the dog I saw was for me?

She knew I wanted one.

I had nagged her about it, but she had told me to stop; we couldn’t have a dog because she had a job and I was at daycare all day. No one would be there to stay home with it, and dogs needed someone to be at home with them.

Dogs couldn’t be left alone.

But what if she had found a way? The woman had disappeared with the dog in the other direction, but it may still have been her. Maybe she was buying it food, or a dog basket?

If I’d had a dog, I wouldn’t be afraid one bit when I was left alone. I wouldn’t complain when Mom had to go down to the laundry room or think bad thoughts when she was out because she had to work late or meet someone.

I wouldn’t have felt sad.

But it was her coat in the hall.

These were just dumb thoughts.

It wasn’t her.

Where was she?

Why wasn’t she here?

Thinking about having a dog seemed to help, even if I was never going to get one; it made me feel braver. I’d get up and fetch the paint box and brushes.

I needed them to paint the teddy, after all.

I counted to three, but it didn’t work on the first try. The light by the counter was on, but the hall was so close and my legs didn’t want to move even though I’d finished counting.

The second try I was on the floor by three and heading for the counter. I moved slowly and carefully so as not to wake what was in the hall, even though I knew it was pointless. It would get me if it wanted to, because it knew all about me and could see everything I was doing.

I didn’t look in that direction.

As I reached for the paint box and brushes, I noticed something else on the counter. A platter.

Why hadn’t I seen it until now?

On the platter were two sandwiches and an apple, and next to them a glass of milk. I touched the glass. The milk was lukewarm.

So this was my dinner. She wouldn’t be back for a while. That’s what it meant.

Something sank inside me. My cheeks burned and I felt a pressure behind my forehead. Why didn’t she say that she’d be gone for this long?

By now I was hungry, and it would have been nice to taste the apple and have some sandwich, but I would not.

She had made it for me, and I didn’t want it.

I put the glass of milk in the fridge, then changed my mind and took it back out. I would leave it all out, untouched, and when she got home she would see that I hadn’t drunk or eaten any of what she had set out for me.

I wondered if her reason for not telling me was related to the last time, when I had tried to make her promise not to go out again. Could it be that she didn’t dare tell me?

Had she really left without saying anything?

Again I walked as quietly as I could, but as I carried the painting supplies to the table my hands were shaking so much the brush handles clinked against the edge of the glass jar, and when I’d put them down and taken a seat, I sensed it had drawn near.

It was in the kitchen.

I couldn’t see it, but I could sense it close by, just beyond the lamplight.

I had to tell her that I couldn’t handle this.

Hadn’t she said that dogs couldn’t be left alone and maybe this also applied to children? Or to me at least–I couldn’t be left home alone, either.

At least not when it was dark.

The blue outside the windows had darkened and turned black.

I wouldn’t do my rounds turning on the lights because it was too late. I couldn’t get up again, I couldn’t leave this glow.

What would happen to teddy?

I couldn’t go get him and I couldn’t go to bed. It felt really late now. When Mom finally came home she would ask why I was still up and I would say that this was all her fault, because I couldn’t go to bed when I was alone.

I couldn’t do any of what she wanted me to do–not eat dinner or brush my teeth or put on my nightclothes. All I could do was sit in this beam of light with my paints. Lucky for me, I had my own important work to do and lucky for me, we had this lamp.

I would stay put until she came home and then I’d show her how busy I’d been, how I hadn’t missed her one bit, because why would anyone miss someone as stupid as she was?

That’s when I heard something.

The elevator door opening and closing, footsteps crossing the entrance hall.

I felt a rush.

The sound came closer, but faded away, and I heard another door on our floor being opened then shut.

I stirred the brush around in the yellow paint and filled in the teddy bear, painting its arms and tummy. She had made me dinner, so she knew she was going to be late and that’s how I knew nothing had happened to her.

I guess something could always happen, but at least I knew she’d be back. There was no way she wasn’t coming back. When she got here, I would tell her that she was never allowed to go out again. Not because I missed her, I wasn’t about to tell her that, but because I couldn’t do anything while she was gone.

I couldn’t even draw and make letters and I had to finish my book, after all. She had said so herself.

I laid across the table with my head on one arm and my brush on the paper. The paint spread but kept smearing. Everything flowed together, my eyes closed by themselves and they were too heavy to open back up.

My hand let go of the brush.

Then the teddy rose out of the picture, even though I wasn’t finished painting. He climbed onto my lap and jumped from the chair to the floor and went out into the hall where he disappeared in the darkness.

I heard him calling for me to join him.

Even though he was just a drawing, I was strangely unafraid when he was with me in the hall. He took me by the hand and led me to my room, shouted ta-dah!, and pointed to the dog in the basket by my bed, which I figured must be the one that Mom had bought.

I leaned over and right as I was about to pet it, I woke up and sensed that she was at home.

She was here and all else had vanished.

When I opened my eyes, she was standing at the kitchen counter with her back to me. My arm ached, but I kept my head where it was and looked at her through half-shut eyes. If she turned around, she wouldn’t notice that I was awake.

She picked up the glass of milk on the counter.

I heard her take a sip, then drain the whole glass.

When she put it down, it sounded like she was going to vomit. She retched and spat in the sink, slurped some water and swished it around in her mouth before spitting it out.

She hadn’t considered that the milk would have been sitting out for hours. Serves you right for being away so long, I thought. I breathed slowly, trying to make it look like I was sleeping.

She put the platter with the sandwiches and the apple in the fridge, then walked over to the table and started riffling through my pictures. I could hear that she was smiling.

She took my painting supplies and cleaned them and left them to dry. First she switched off the lamp over the sink, then the one above me before bending down and grabbing hold of my body, lifting me up in her arms and carrying me through the hall.

I wanted to put my arms around her neck, but if I did I might not be able to stop myself from opening my eyes, looking up at her, and smiling, and I didn’t want to do that.

She carried me into her room and laid me in bed, put on her nightgown, crawled in beside me under the covers and whispered:

Good night, precious.

A patch of sky peeked through the shades and I saw that it wasn’t night at all anymore. The black had faded into blue and light was seeping into the colors. I closed my eyes and pretended to roll over in my sleep, so I could be closer to her.

I wanted to put my arms around her neck, but if I did I might not be able to stop myself from opening my eyes, looking up at her, and smiling, and I didn’t want to do that.

She carried me into her room and laid me in bed, put on her nightgown, crawled in beside me under the covers and whispered:

Good night, precious.

A patch of sky peeked through the shades and I saw that it wasn’t night at all anymore. The black had faded into blue and light was seeping into the colors. I closed my eyes and pretended to roll over in my sleep, so I could be closer to her.

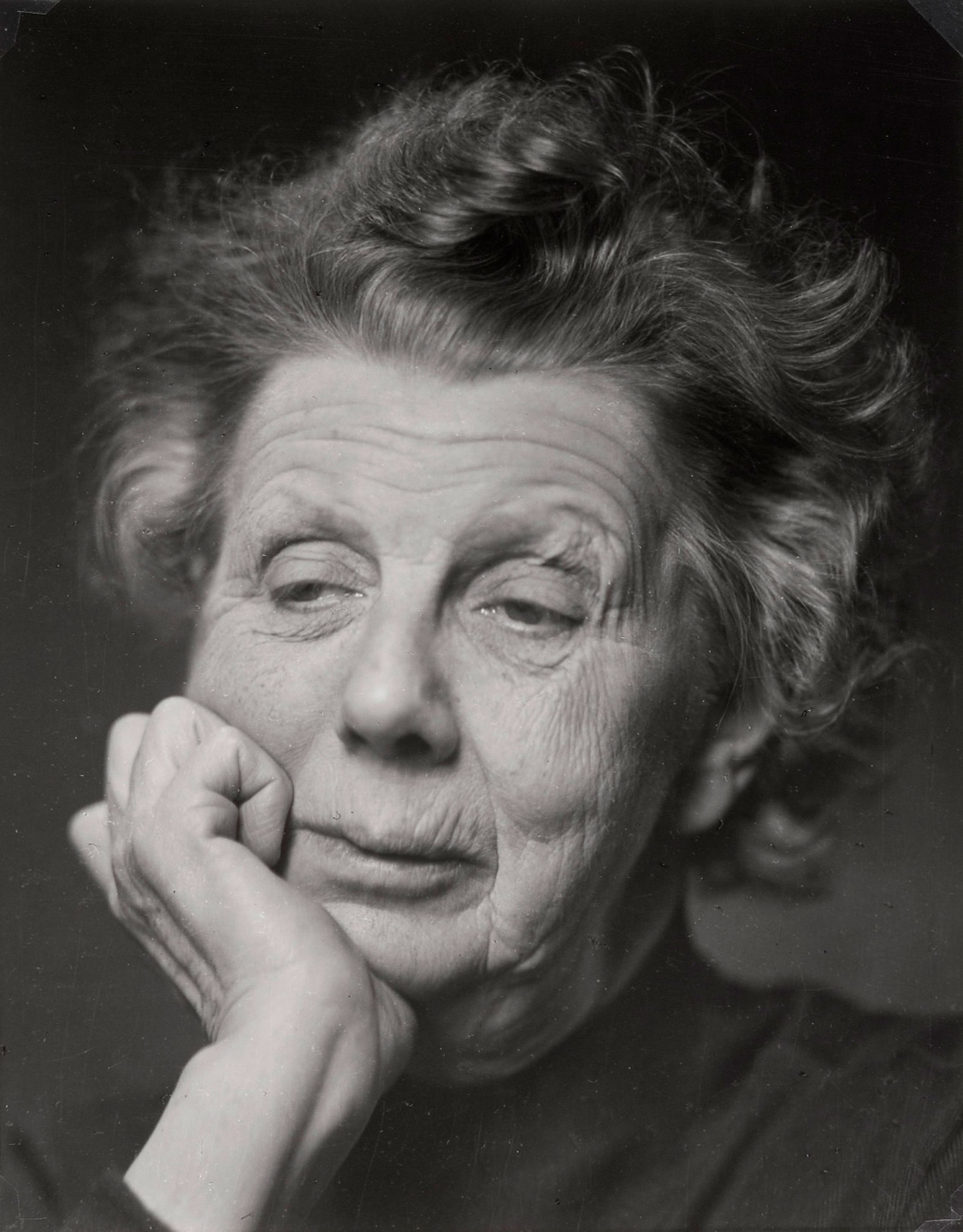

KAROLINA RAMQVIST

Karolina Ramqvist was born in Gothenburg in 1976 and grew up in Stockholm. She is a journalist and critic and wrote the famous music essay “När svenska pojkar började dansa” [When Swedish Boys Started Dancing] in 1997; two years later, she contributed to the feminist anthology “Fittstim”.

In addition to criticism, Karolina Ramqvist has been a reporter, a writer of short stories and essays, and a scriptwriter and editor in chief of the journal Arena. Her first novel, “More Fire”, published in 2002, highlights tourism as a postcolonial practice on Jamaica. Her breakthrough as an author came seven years later, with the novel “Flickvännen” [The Girlfriend].

Karolina Ramqvist’s five novels have been translated into some fifteen languages and won numerous awards, including Tidningen Vi’s Literature Prize, the 2015 Per Olov Enquist Prize and the Stina Aronson Prize which is awarded by Samfundet De Nio. Her sixth novel, “Bröd och mjölk” [Bread and Milk], will be published in spring 2022. Karolina Ramqvist lives in Stockholm with her husband and three kids.

“When I was asked to write a story based on a work in the collection, my first intention was to choose Christodoulous Panayiotou’s terracotta floor “Days and Centuries” from 2013, which is something entirely different to these paintings from the 1930s, “Lamplight” and “Stories”. But I kept coming back to them, no matter what. Vera Nilsson’s paintings have an evocative power, and I am compelled by the way she portrays children. I wanted to immerse myself in her world and write while spending time with her subjects which were so contrary to the old ideals on how children should be represented but also raises questions about our contemporary view on children. Her images are so imbued with living realism and brutality that I feel I can see myself in them.”

VERA NILSSON

Vera Nilsson was born in Jönköping in 1888. She trained to be a drawing teacher and then went to Paris in 1911 to study under artists such as the famous cubist Henri Le Fauconnier. In the years leading up to the First World War, Vera Nilsson travelled around Europe, before returning to Sweden and settling in Stockholm.

Her first exhibition was in Copenhagen in 1917, together with the painter Mollie Faustman. In 1933, Vera Nilsson’s first solo exhibition opened at Konstnärshuset in Stockholm. She continued to travel throughout life, frequently visiting France but also New York, Senegal, and Martinique. In 1954, Vera Nilsson became the first female member of the Academy of Fine Arts since 1889.

As an artist, Vera Nilsson was one of the most prominent Swedish expressionists and a radical regenerator of imagery with children. Her paintings are free from stereotype images; children are portrayed without symbolism or staged settings, doing ordinary things. The oil painting “Lamplight” (1930) was acquired for the Moderna Museet collection in 2002, in connection with the exhibition In the Age of Aberration – Sketchbooks, Drawings and Paintings by Vera Nilsson, and the girl is her daughter, who later became an artist, Catharina Nilsson-Gehlin (1922–2015), nicknamed Ginga.

The painting “Stories” (1933) is also oil on canvas; it was acquired in 1936. On the back it says “Work by mummy and Ginga”.

Vera Nilsson was politically aware and strongly committed to helping the needy in society. She was committed to international democracy and proposed that art should be shown in public spaces, such as underground stations. The T-Centralen underground station was opened in 1957; one of the works there is by Vera Nilsson, “Det Klara som trots allt inte försvinner”[The Klara that Nevertheless Remains], a glass and stone mosaic on a concrete pillar.

Vera Nilsson died in May 1979, aged ninety.

“Stories, Lamplight” is an independent sequel to the project Moderna Museet &, which was launched in May 2020 and involves inviting arts practitioners to seek inspiration in the Moderna Museet collection and then create something in their respective fields.

The first was El Perro del Mar, whose visits to the Moderna Museet collection inspired her Grammis-nominated album FREE LAND

“Stories, Lamplight” is published by Moderna Museet and for sale in our shop.

Stories, Lamplight

by Karolina Ramqvist

Editor: Kristin Lundell

Copyeditor: Tina Rabén

Translation to English:

Saskia Vogel (Ramqvist)

Gabriella Berggren (Biographies)

Production manager: Teresa Hahr

Design: Frans Enmark

©2022 Moderna Museet, Karolina Ramqvist

Vera Nilsson/Bildupphovsrätt

Photo: Prallan Allsten/Moderna Museet

Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

Åsa Lundén/Moderna Museet

Anna Riwkin/Moderna Museet

Published 18 January 2022 · Updated 7 February 2023