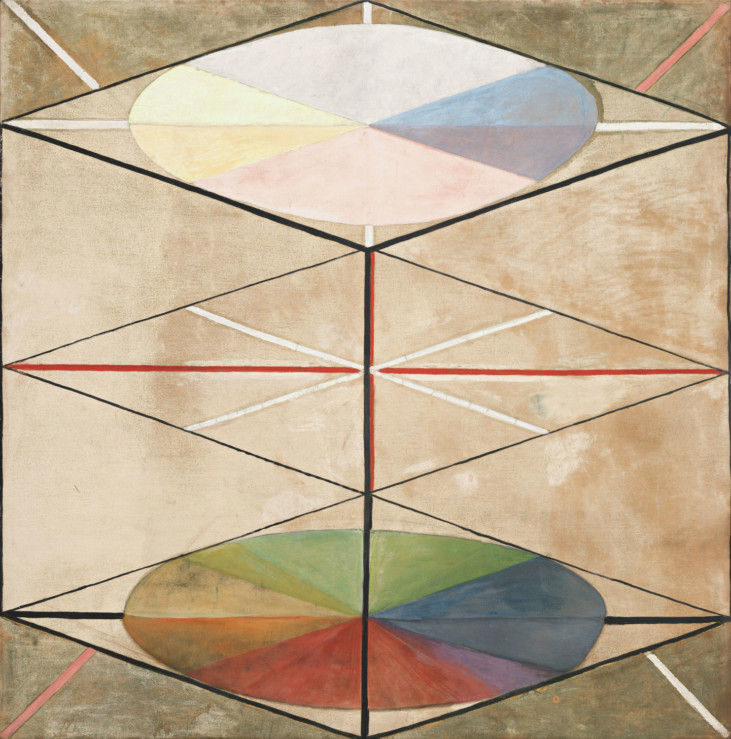

Anna-Chaja Abelevna Kagan, Suprematistische Komposition, 1922-23 © Anna-Chaja Abalevna Kagan

Foto: Prallan Allsten/Moderna Museet

9.11 2010

The Second Museum of Our Wishes: Anna Kagan

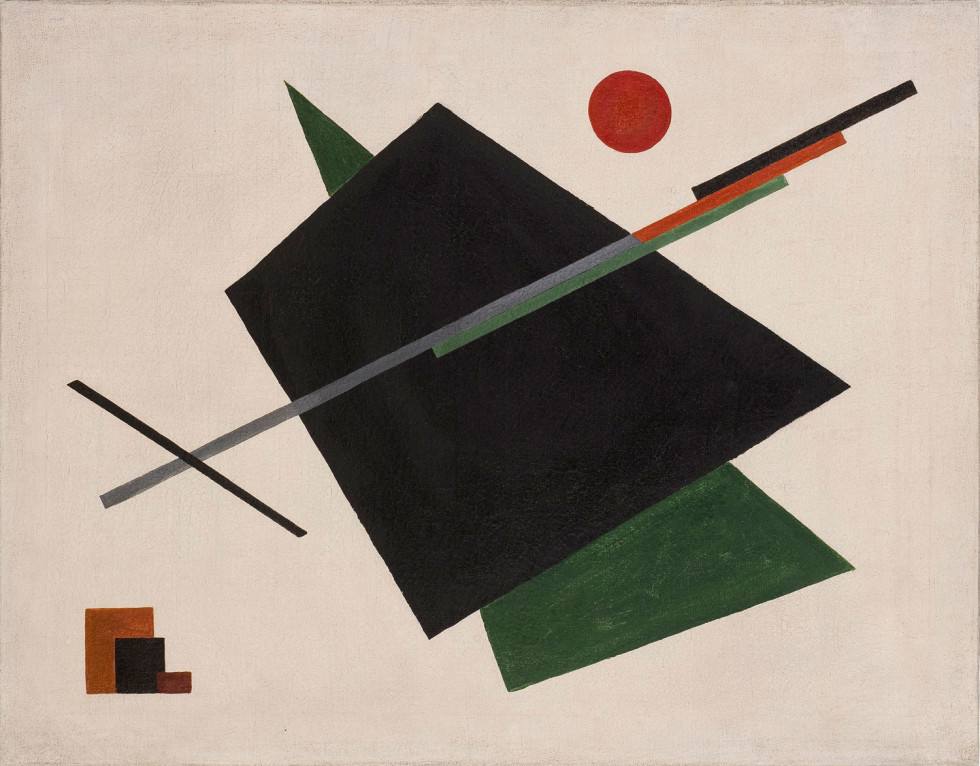

Malevich, who began teaching at the college in the autumn of 1919 at the invitation of its founder, Marc Chagall, reformed it into a suprematist centre. Vitebsk was a veritable second Paris in those days. Malevich left the college and the town in April 1922, however, after the authorities had turned against the Russian avant-garde.

Kagan was a member of the UNOVIS group, which Malevich had been involved in starting. Malevich and his suprematist visions had a strong infl uence on Kagan. His visions had developed from the ideas of futurism, and the fi rst time Malevich showed his suprematist art was at the exhibition 0.10. The Last Futurist Exhibition, in Petrograd in 1915. This event marked the breakthrough of abstract, non-objective art. The intention, according to Malevich, was to “liberate art from the meaningless burden of objects”.

Together with the UNOVIS group, Kagan participated in exhibitions in Vitebsk (1920, 1921), Moscow (1920, 1921, 1922) and Petrograd (1923). With suprematism, art had reached ground zero. Or, as Malevich put it: “By ‘Suprematism’ I mean the supremacy of pure feeling in art. To the Suprematist fi gurative expression is meaningless in itself; the signifi cant thing is the feeling, regardless of the circumstances under which it arose.”

In Kagan’s Suprematist Composition from 1922–23 upward-soaring geometric forms hover in several levels above one another in the pictorial space against a white background. A red circle above to the right provides a colour accent and balances the dynamic composition, together with the three overlapping squares at the lower left-hand corner.

Kagan continued to paint non-fi guratively and never converted to the doctrines of social realism that were introduced under Joseph Stalin. She was not allowed to exhibit, however, in the new artistic climate. Between 1928 and 1930, she transformed suprematist abstraction into architectonic paintings, and in the late 1920s and early 1930s she translated her abstract compositions into ceramic utility objects. She also continued to paint in obscurity until her death. Although her later paintings retained abstract elements, these were contrasted with fi gurations of a surrealist and symbolic kind.

Anna Kagan born 1902, Vitebsk, Belarus – dead 1974.

Read about The Second Museum of Our Wishes

Published 9 November 2010 · Updated 15 February 2016