Elmgreen & Dragset, Boy Scout, 2008 © Elmgreen & Dragset / Bildupphovsrätt 2019

16.4 2019

Four galleries of contemporary art – Re-hangings in the Collection

Together

16 April 2019–3 January 2021

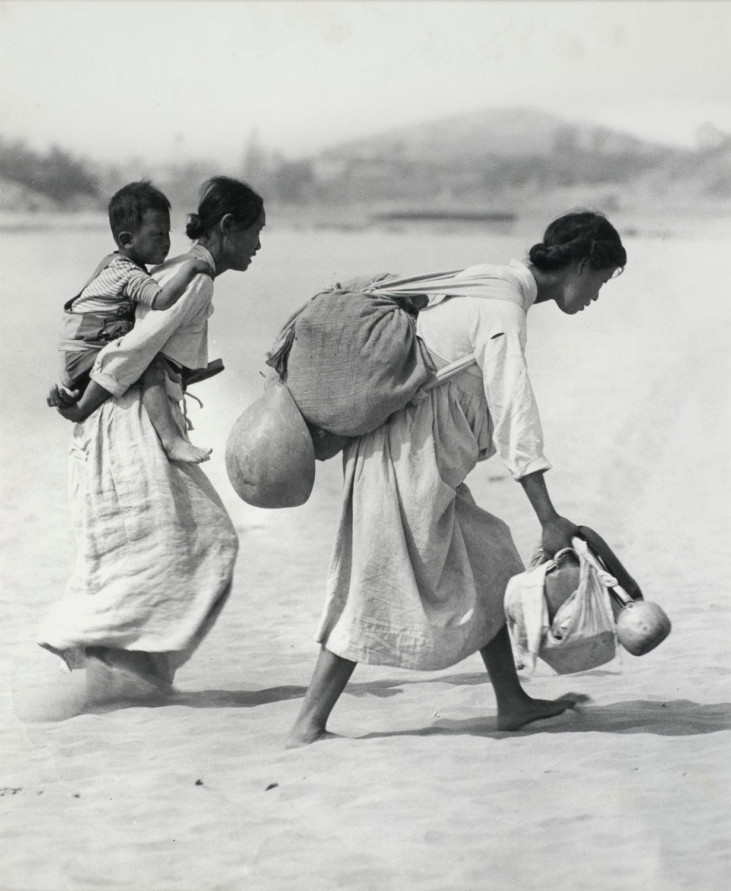

In Sweden, the word solidarity is strongly associated with the 1970s, when manifestations were frequently organised in the arts. In 1969, a wildcat strike broke out at the LKAB mining company in Norrbotten. Fundraisers were arranged to help the miners, and open meetings were held also at Moderna Museet in Stockholm. The following year, a solidarity evening took place at the Museum in support of the Black Panther Party, and a few years later, in 1978, an exhibition showed works donated to the International Museum of the Resistance Salvador Allende in Chile.

Fia Backström’s ”The Worker through the Ages” (2010) includes six historie works from the Moderna Museet collection, exemplifying how art and solidarity movements have joined forces. From 1930s workers’ art to 1970s strike art for dignity, better working conditions and higher wages. The work urges us to look for similar expressions of care, community spirit and collective forces in art from more recent years in the Museum’s collection.

The other works in the room are ”Gallok -Kallak” (2013) by Katarina Pirak Sikku, ”549 kg poster” (2017) by Pratchaya Phinthong, and parts of Emily Jacir’s series ”Where We Come From” (2002–2003). These pieces acknowledge and give us insights into situations relating to labour law, migrant workers, land ownership and limitations in the freedom of movement. These artists stand up for people in vulnerable situations and give them support, visibility, a voice, and, in Emily Jacir’s case, practical help.

Mental Maps of Power

In Ola Pehrson’s ”hunt or the unabomber” 2005 we enter the mind and history of the antisocial outsider. Known as the Unabomber and working alone from the 1970s until his capture in 1996, the US terrorist Theodore Kaczynski was a former maths professor who distributed mail bombs to academics and executives involved with research and development of new technology.

Pehrson’s installation recreates a tv documentary on Kaczynski, in ephemeral materials and by displacing the filmic narrative to small maquettes and other, more or less fact-based documents. Prominent in the work are the play dough heads that seem to leap between dimensions and media, appearing as flat images in one moment and as three dimensional fictions and sculptural objects the next.

Pia Arke created her grainy photographs in the ”Kronborg” series (1996) with the help of a homemade camera. The images, displaying the Danish castle Kronborg in ghostly vistas and overlaid by shadows of the artist’s body, call to mind Shakespeare’s ”Hamlet” that takes place here, with its story of guilt, retribution, and haunting. A symbol of the Danish crown, Kronborg would have a particular charge for Denmark’s historie colonial relation to Arke’s homeland Greenland.

The two works deal with exploring technologies and forging mental maps with which to make dominant power and the ghosts of history appear. Regardless of their widely different styles and subject matters, these works are also meditations on how to create new versions of reality in order to tel1 other histories. Art history echoes in them, such as the playful methods of Oyvind Fahlström (1928–1976), or Salvador Dali’s (1904–1989) technique of applying self-induced paranoia as a vehicle for image making.

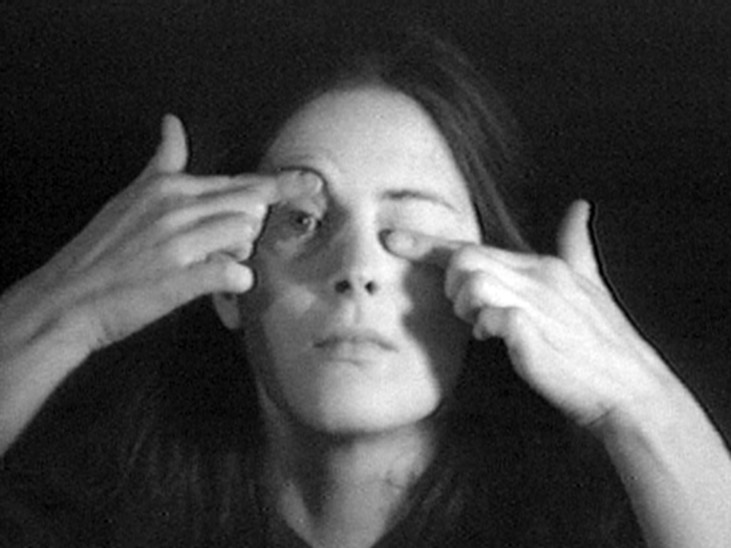

Strangely Familiar

What psychoanalysis calls das Unheimliche is literally the ”unhomely”, or in English the uncanny. To thinkers from Sigmund Freud to Julia Kristeva, the uncanny addresses what is strangely familiar: when what is well known and safe turns into something deeply ambiguous that provokes fear and disgust. When this happens, perception and cognition are rendered unstable because they have been eerily displaced by small, but decisive changes in the field of the visible. You may wake up in your own bed, but home is no longer home.

The uncanny reveals how that which we identify as our self relies on the getting rid of what is considered alien and abject to it. This means that what is expulsed is involved in regulating identity, albeit negatively. Apart of our desire continues to be unconsciously bound to what is liminal or attempted pushed outside.

A preoccupation of artists working in the 1980s and 1990s, the uncanny was more than a renewal of surrealism’s dialogue with psychoanalysis. At this point, artists worked in the wake of modern art whose forms, content and ideals had been fundamentally questioned. As a theme the uncanny was now set to work within artistic media too, often with an uncompromising viscerality that debunked art’s inherited cultural authority. The sense of a historie homelessness within art’s means of expression would not be new to communities who bore the burden of power relations formed along the lines of race, gender and sexuality.

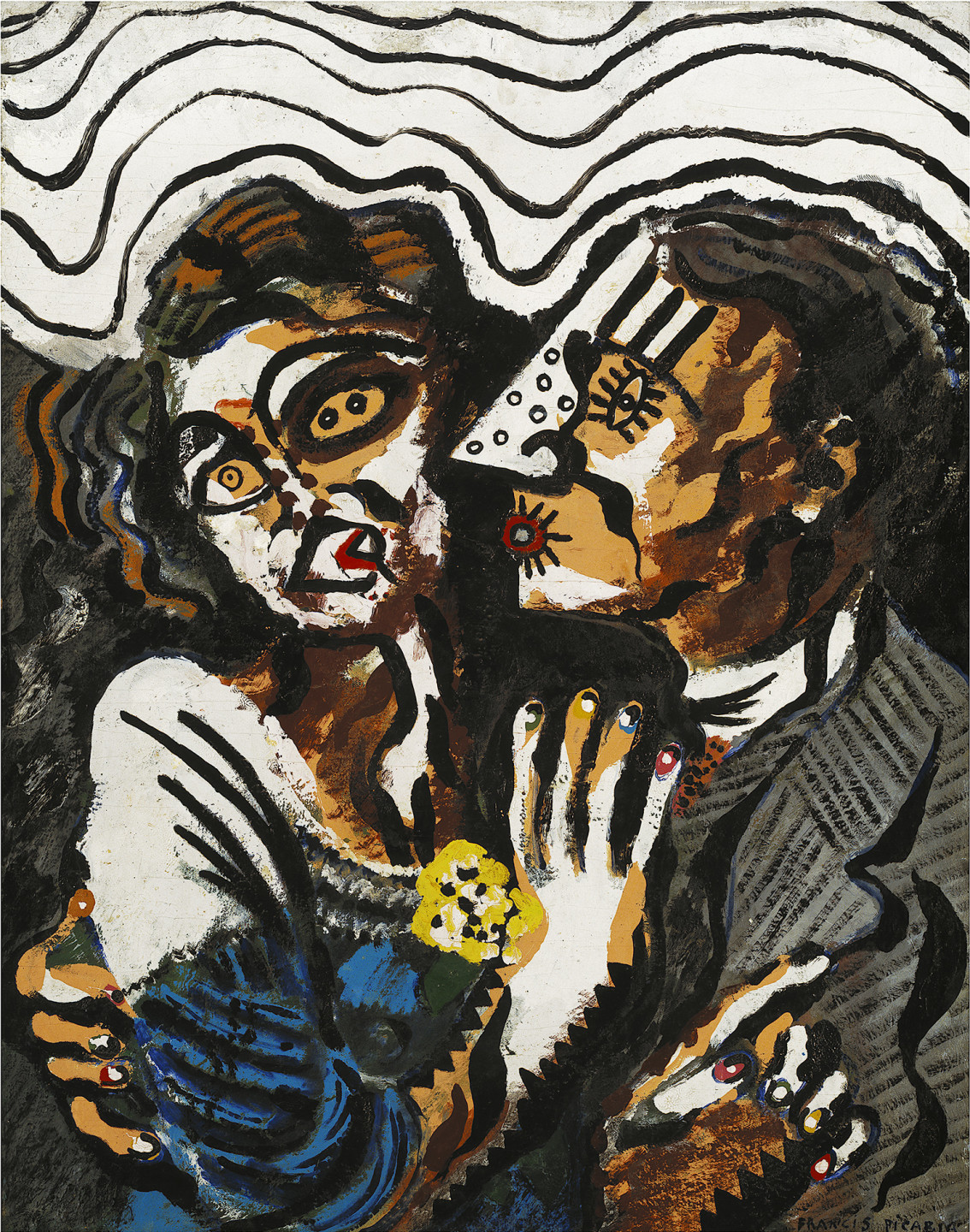

After the Wall – Before the Curtain

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 marked the end of the Cold War, and the beginning of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Fifteen now sovereign nations dismantled their political system almost overnight, triggering profound social change. The art scene also exploded in the 1990’s and became an increasingly global arena. where biennials and art fair, played a more important role. In that decade, a young generation of artists from the former Eastern bloc stepped onto the international scene, but they were embraced with the tacit expectation that their art would focus on dealing with the Soviet legacy. This ambiguous welcome created a paradoxical climate for many artists. who were at last free to work beyond the looming shadow of cultural ministries and state propaganda.

In the first decade after 1989, however, artists on both sides of the former Wall tended to look back upon the socialist era, whereas society in general was distinguished by a deep desire to move on. With an unsentimental approach, artists challenged the ideological systems and aesthetic traditions that had formed their own upbringings, but also the growing social divides and the far-reaching privatisations that followed in the wake of the new economy. Other artists reflected on the experiences of loss and homelessness caused by the drawn-out wars in former Yugoslavia.

In connection with the major exhibition ”After the Wall: Art and Culture in post-Communist Europe” at Moderna Museet in 1999, the museum acquired several works by artists from the region, some of which aremshown in this room. This exhibition launched prominent international careers for many of these artists.

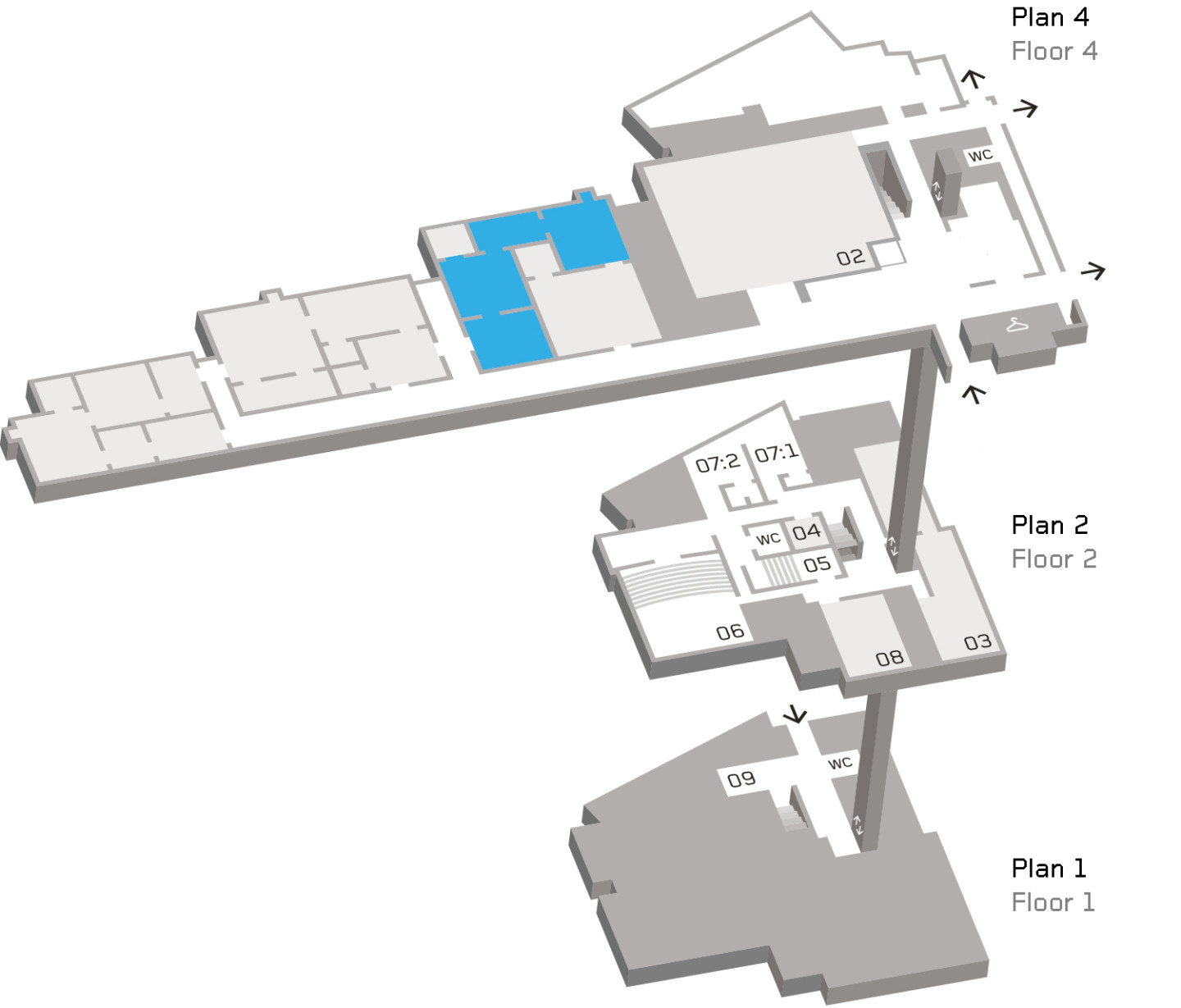

You find the galleries in the Collection on floor 4

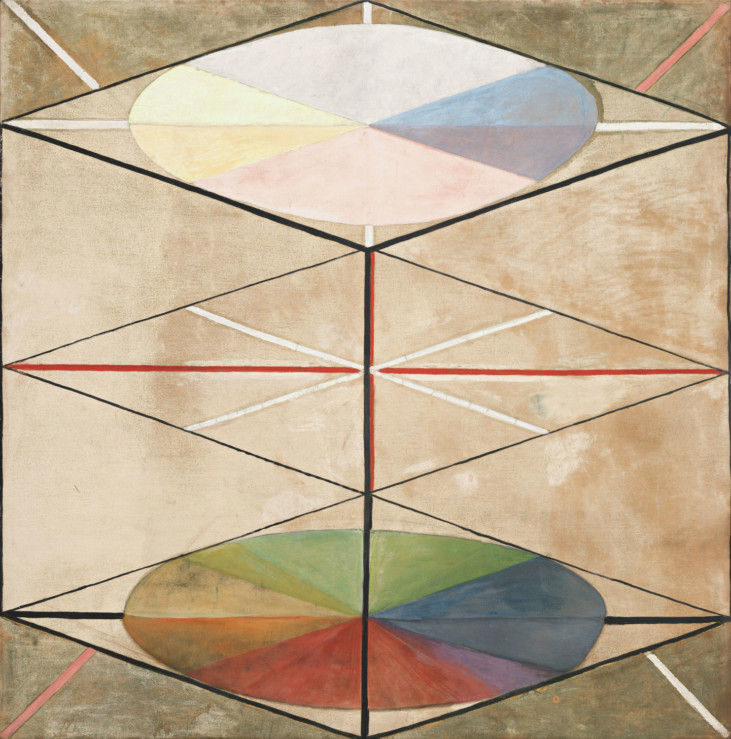

A new presentation of the Moderna Museet collection

A museum collection can be presented and interpreted in countless ways. Throughout 2019, the Collection will be in focus even more than usual, with a major new presentation that will unfold gradually in all the Museum’s collection rooms.

The art will be displayed thematically to a greater extent than before, to highlight new contexts. The new presentation is largely chronological, with occasional surprises by juxtaposing early key works with recent 21st-century acquisitions.

The ambition is to visualise even more narratives about the past and present. One premise for the new presentation is that history is not static but is constantly read and interpreted from a contemporary perspective. Therefore, several versions and interpretations of the Moderna Museet Collection will follow.

More on the Collection: Moderna Museet Collection

Published 16 April 2019 · Updated 16 March 2021