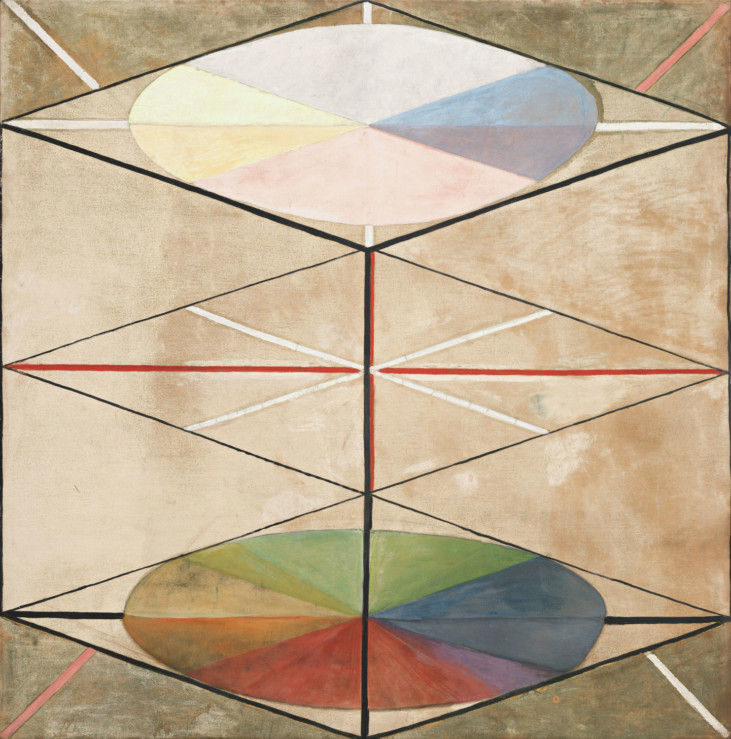

Frederic Matys Thursz, Vermilion II, 1983. Oil on canvas. Phil Sims, RGBY (Red) and RGBY (Green), 1983. Oil on canvas. Alan Uglow, Standard III, 1993. Acrylic on canvas. Photo: Åsa Lundén/Moderna Museet © Frederic Matys Thursz © Phil Sims © Alan Uglow

12.12 2018

News in the Collection: Towards Pure Colour

The history of painting in one colour – monochrome – is as old as modern art. This kind of painting can produce a shock effect nonetheless. Monochromes appear simple because they lack traditional motifs. Rather than tell a story, they occupy physical and mental space. This combination of surface and possible metaphysical depths has both provoked and led to monochrome paintings being analysed and admired.

The first artist to have shaken up the art world with monochromes may be the Ukrainian born Kazimir Malevich, known for single-coloured geometric shapes in his paintings. When one such work, he referred to them as Suprematist, was first shown in Saint Petersburg (then Petrograd) in 1915 it was hung in the “beautiful corner”, where the icons are usually placed in Russian Orthodox homes. Since then monochrome or almost monochrome painting has followed several different paths in the history of art. In the 1950s a movement arose called Colour Field Painting, associated with the critic Clement Greenberg, who, however, preferred the term Post-Painterly Abstraction. In the same period Minimalism emerged – works of art that were not supposed to refer to anything beyond themselves.

The new presentation in the collection is a room of paintings of the last seven decades, all monochromes. Or are they? Marcia Hafif’s Transparent Painting: Ultramarine Blue is not just blue but black and turquoise as well. In Robert Ryman’s work the glass fibre fabric can be seen in the marks left by the tape he used to stick it to the wall prior to painting. The material in Magnus Wallin’s ”Are you in pain… Not anymore” is dried blood, which has no definitive colour but is a living, shifting shade of lilac-brown.

The qualities of the pigment, how it was applied and with which tools, all influence the impression created by the paintings. Shadows appear, depths emerge. Even though the dissimilarities between the works are greater than their similarities, the paintings emit a similar energy, a low-intensity sense of rest, concentration. In “The Silent Art” (1967) the American art historian Lucy Lippard defined this kind of art as: monotone painting.

Free admission th the Collection. Welcome!

More on the Moderna Museet Collection

About the presentation in the museum: Moderna Museet Collection

What is on view right now? Search the Collection

History, research, conservation etc: About the Collection

About the donation

Published 12 December 2018 · Updated 12 December 2018